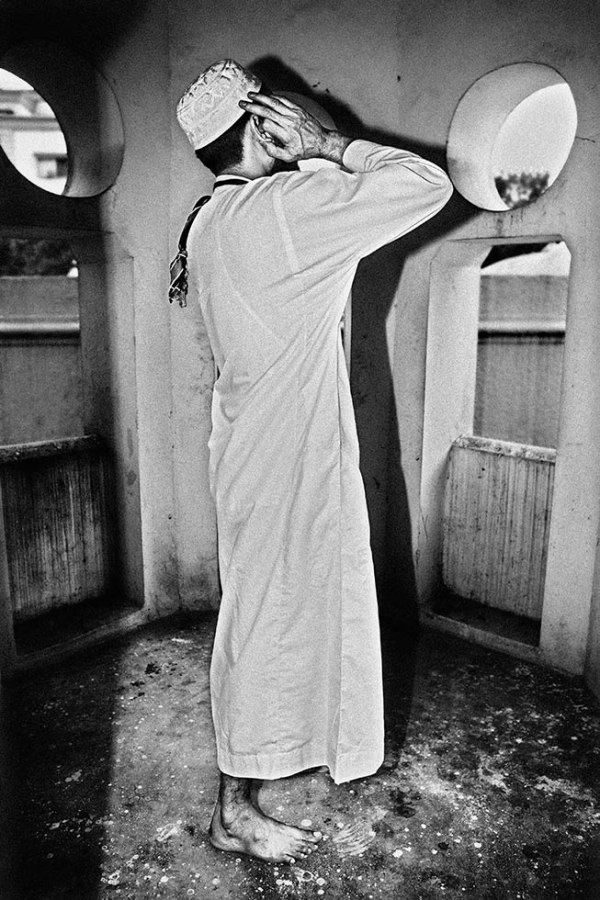

Interview: Photographer Sheds Light on 'Inner Face' of Bangladesh's Gay Community

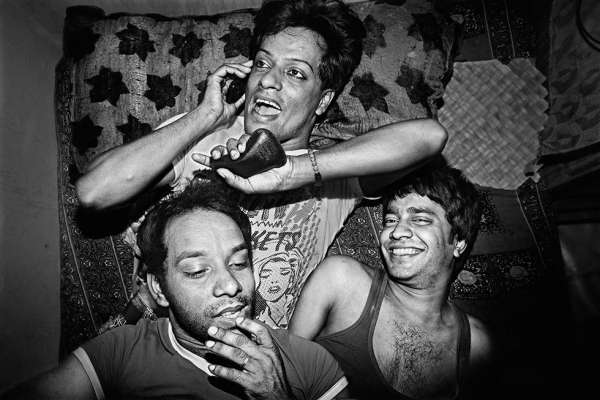

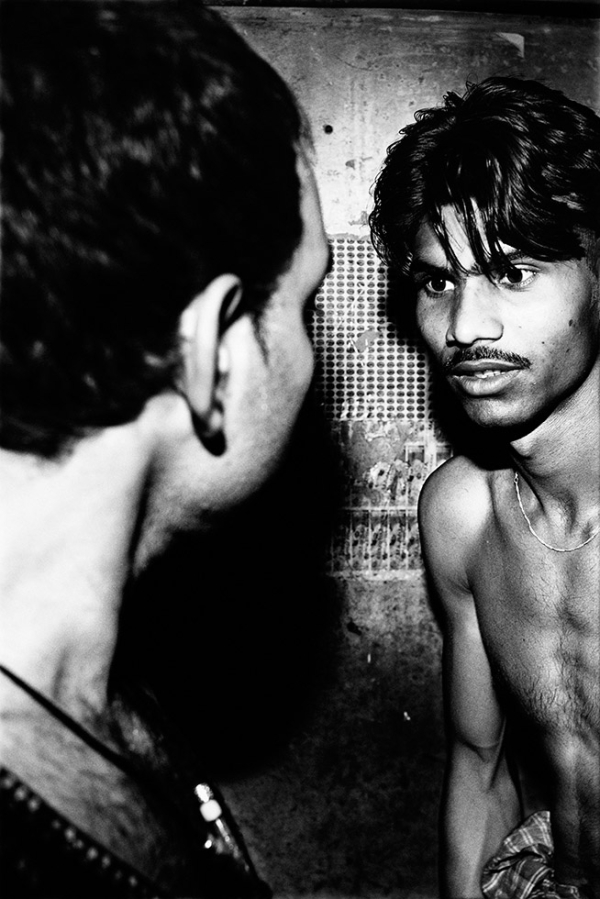

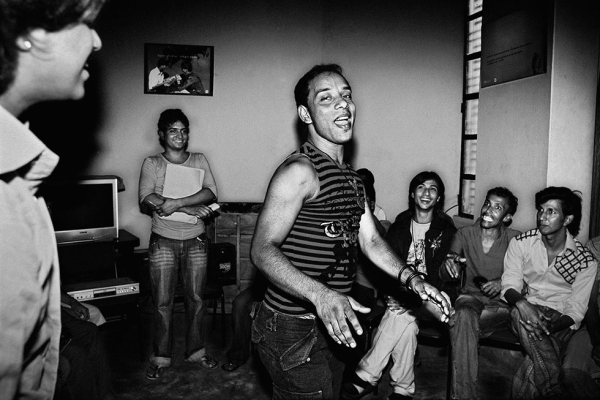

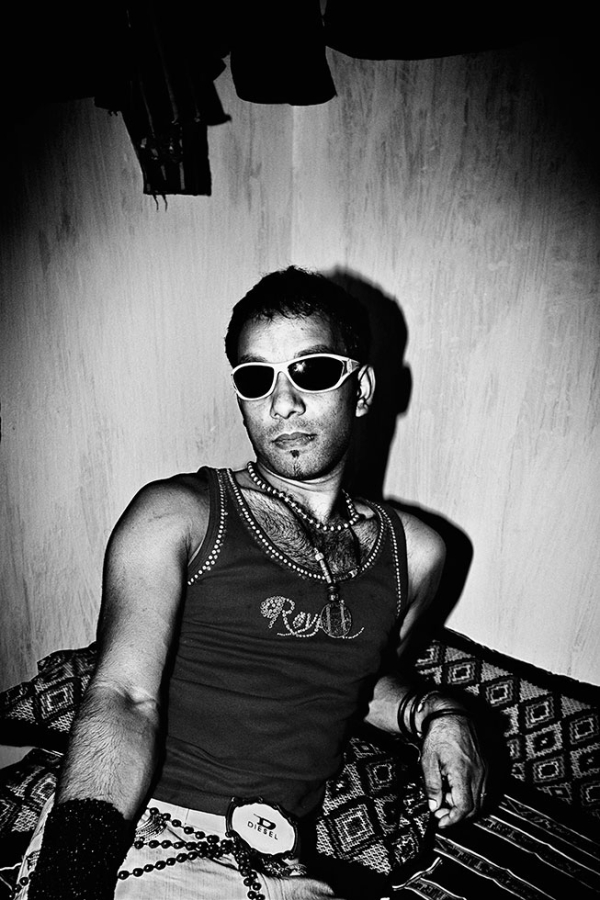

Bangladeshi photographer Gazi Nafis Ahmed has a knack for digging deep and finding stories in his home country that few have focused on. Last April his series Made in Bangladesh was featured on Asia Blog a mere 13 days before the Rana Plaza factory collapse in Dhaka that killed more than 1,100 people. With his latest series, Inner Face, Ahmed turns his lens on Bangladesh's gay community.

Homosexuality is illegal and punishable by law in Bangladesh. Section 377 of the country's Penal Code is a memento left behind by the British colonial authorities that "criminalizes anal sex between men and other homosexual acts." The law, or some model of it, is still in effect in over a dozen former British colonies. Australia, Fiji, Hong Kong, and New Zealand are among the few that have repealed it.

In the past year, LGBT rights in Bangladesh have made the news like never before, after the government rejected a recommendation by the United Nations Population Fund to abolish the laws outlawing homosexuality. Supporters of the LGBT community, such as the Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus, have faced a backlash from the nation's Islamic groups. But this conversation only seems to be gathering more traction and Ahmed's photos are a powerful tool for shedding light on a community that currently lives in fear of retribution.

Ahmed is a participant in New York City's VII Photo Agency Mentor program and his work was recently exhibited at the Dhaka Art Summit. We reached out to him through email to find out more about Inner Face.

For the benefit of those who may not know much about Bangladesh, can you describe, briefly, how homosexuality is perceived there, and how Bengali society reacts to same-sex relationships?

Any discussion around sex and sexuality is taboo. It is a family-oriented, moderate, Muslim society with strong economic class structure. The sporadic discussions online have been mostly negative, with people calling homosexuality a sin, a psychological disorder, or just perverted behavior. However, there is a pocket of tolerance and acceptance depending on the social class. The human rights movement and the development sector are increasingly supportive of LGBT rights. The government, specifically the Health Ministry, has extensive HIV/AIDS policy that includes Men having Sex with Men (MSM). There are also several NGOs working with MSMs and the Hijra comunity, but there is no formal organization working for the LGBT community.

And last but not least, there is penal code 377, which is a British colonial law criminalizing "unnatural sex." The law has never been implemented but is regularly used to harass LGBT people.

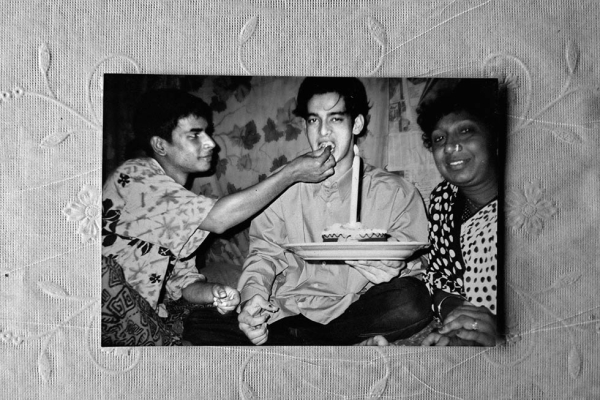

Most of your subjects seem at ease in your photographs. How did you find them, and were there any initial obstacles?

It has been a long journey. It took me a year before I started to photograph. I had to gain their trust. They have never been photographed before in the context of homosexuality. I want to thank Bandhu Social Welfare Society. They collaborated with me.

Was it a conscious choice to photograph only men, or were you unable to find female subjects for the series?

That is an important question. Back in 2008 the response I received was "we are not ready." Being a part of the patriarchal society, women's sexuality is absolutely silenced and lesbians are a minority within a minority. But in the next chapter of my work you will find them.

What was the most eye-opening experience for you during the making of these photos?

It's important to realize that we are all human beings. No matter what our sexual orientation is. What's more important is you need to be a better human being. Most people find that to be the hardest.

How have people in Bangladesh reacted to this story since its publication?

I have had great positive response from the audience. Three of the gay men from my series got jobs after they were seen through my work. Recently it was exhibited at the Dhaka Art Summit, curated by renowned art historian, critic, and curator Deepak Ananth. Photography is a very powerful tool. It is a universal language and the most democratic art form. It changes society, unites the world. I cannot think of anything else than the way photography can impact the collective mental state.

Recently, I have also been commissioned to continue the project and work with the whole LGBT community. I would like the ongoing work to travel across the world and to make a book, so it can reach the wider global audience. But making it come true requires the financial support and facilities. I welcome international institutions to collaborate with the project. Audiences can also connect with me through my Facebook page, which I will be updating.