Interview: Novelist Mohsin Hamid Wants You to Get 'Filthy Rich' in a Rising Asia

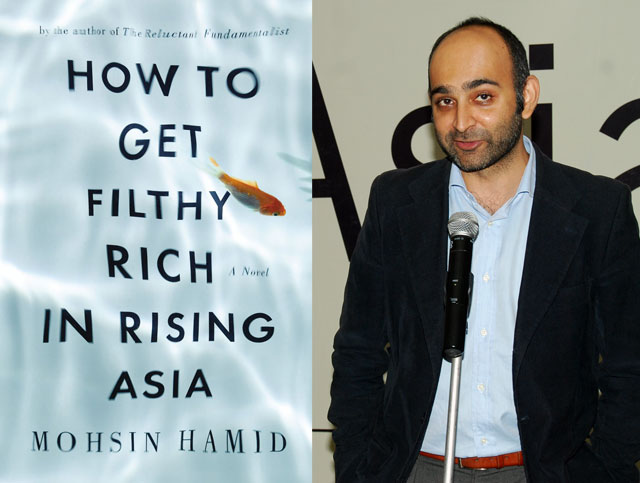

L: American cover art for "How to Get Filthy Rich in a Rising Asia," the forthcoming novel by Mohsin Hamid (R), shown here at an Asia Society India Centre event in Mumbai in Dec. 2012.

KARACHI — Among the many authors, artists, poets, performers and activists convened here by the fourth annual Karachi Literature Festival last week, one of the most prominent was Pakistan's own Mohsin Hamid, on hand to introduce his latest book, How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia.

Named one of the "most anticipated" releases of 2013 by literary site The Millions and already excerpted in The New Yorker, How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia purports to be a self-help book with unnamed characters set in an unnamed place that is loosely based on Lahore, where Hamid lives. In another departure from novelistic norms, the book is written in the second person. "You are the central protagonist," Hamid told Asia Blog, "you the reader are also you this character who is a young boy, initially dirt poor, in a village [who] moves to the city. It follows him from birth until death as he tries to get wealthy and falls in love with this girl he is sort of pursuing his whole life. We end with him in old age."

"It's not based on any person as such and he doesn't stay a boy. He's 80 years old and decrepit by the end of the novel, so each chapter follow him five or seven or ten years further on in his life and he's you. He is the vehicle for the reader who is reading this self-help book/novel to learn how to get filthy rich in rising Asia supposedly but actually perhaps to learn something else."

Speaking about the intended audience for English-language novels by Pakistani writers, Hamid said, "in terms of who I write for, I don't think of it as a geographic thing so I write novels that i would like to read. I write novels about stuff that I care about. So, whether it's a housewife in Chile or a college student in America or one of the young attendants here who just told me that she just picked up my book at local Karachi library, those are all equally valid readers as far as I'm concerned."

Hamid's first novel, Moth Smoke, has been translated into 30 languages. He doesn't see himself as someone who can write in languages native to Pakistan, however. "I have thought about getting my books translated, and the chapters in Moth Smoke have been translated and I think that makes sense — the idea of trying to find a greater Urdu-language connection for the writing is probably important," he said. "My first novel came out as an Urdu telefilm on GEO Tv and is hopefully now being made into into a film by Rahul Bose. The second one [The Reluctant Fundamentalist] came out as a movie as well so they have ways of working in to the popular culture."

“For me, I don't write in Urdu, I studied Urdu through high school so I can read it and write it very badly, but I cannot write a novel in Urdu. I couldn't even write a decent essay in Urdu. It's like saying you're a sculptor, but people like paintings, why don't you paint? I'm just an English-language writer. I don't have another language to write in."

With two of his books being made into films, Hamid admitted that he writes with the consciousness that his work might be adapted for the screen. However, he intentionally tries to write novels that do things that films can't do. He believes that makes it difficult for anybody who wants to make his novels into films, as Mira Nair has discovered with her adaptation of The Reluctant Fundamentalist, and as he thinks Rahul Bose is probably discovering right now.

"Moth Smoke is sort of this surreal trial where all these different characters are talking and you can distill out of that the story of a guy who smokes pot, falls in love with his best friend's wife and becomes a heroin addict, but that story is only part of what Moth Smoke is," explained Hamid. "Similarly, with The Reluctant Fundamentalist, you can take the story of a man who goes to America and comes back, but the novel actually is a half conversation where you hear one side of two people talking, and doing that cinematically is next to impossible. You don't want to see just a guy sitting there talking at the camera for two hours."

"The new novel is a self-help book told about 'you.' Again, you could make it into a movie about a young boy who grows up and falls in love and gets old, but they are intrinsically novels. I try to write novels that do things that only novels can do. If I've learned anything from being involved in making films, it's that there are certain things that films do well and there are certain things that films can't do, and the things that films can't do interest me."

Hamid wants to write novels that are unlike anything he has read. The best novels he can imagine writing are those that push the form and reinvent what the novel does.

"When I wanted to write Moth Smoke, it wasn't just that I wanted to tell about this urban youth that I hadn't seen in fiction, in this sort of magical or traditional fiction of South Asia. It's also that I wanted to write a novel that structurally did things I hadn't seen done before. That has been my project throughout, The Reluctant Fundamentalist does that and this book I think probably more than either of the two. The reason to do that is because form is how you get your story into a reader's mind. It's how you cross over from writer to reader and unless you think people haven't changed and the human context hasn't changed at all, that the basic storytelling form that we've had for thousands of years are still the only form. Unless you think that, you have to find new ways of telling stories. In today's world, where people are watching TV, they are on Twitter, and they are absorbing lots of different types of things, we need new kinds of novels. That's what I'm trying to do."

The author cautioned, though, that he doesn't want to experiment solely for experimentation's sake. "Ideally, many readers will just read these books and say that was a great story and not even realize that it was formally experimental. Other readers might find that it is experimental."

In Hamid's earlier novels, the protagonist is a young man who isn't that different in age from him. In the third book, he wanted to take on a broader canvas, which is why he built the story around the character's journey from poor village boy to destitute city kid all the way up to corporate tycoon on the verge of death. "I wanted to get outside of personal experience and just write purely imaginatively," he said. However, Hamid points out that in Moth Smoke as well there were chapters written completely from a woman's perspective, and he can certainly imagine writing a whole novel from a woman's point of view — although he hasn't done it yet.

The storyline of How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia, Hamid agreed, is a popular Bollywood story, but he believes that it is a popular human story as well. "What's interesting to me about it was that I was less concerned with how do you get rich. Although, I'm interested in that and the violence and the cruelty of the process. But it was more that if I followed him through all these different slivers, I would have a way of writing about many different social classes from really poor to middle class to wealthy. For me the beauty of writing this kind of a story is that you can break outside of single class restriction and go across the society."

Hamid has been conscious of visible class difference from a very early age. At age nine, when he moved back to Pakistan from California, he was shocked by the presence of servants in his grandfather's house. Hamid described his grandmother, a chairwoman of All Pakistan's Women Association, as a real crusader for workers rights and women's rights, therefore he found it strange to have servants in the house. He recalls asking his mother if they were slaves. Although, she explained to him that they were not slaves, Hamid claimed that he never recovered from the shock of servants as a concept. "I still look around me and when I travel in India and Pakistan, I'm always sort of shocked at the different levels in our society, it never goes away."

Finally, Hamid expressed his disappointment that writers from India were unable to be part of this year's Karachi Literature Festival. Some of the Indian literary figures who were expected to be present were unable to attend for various reasons. Indian poet and lyricist Gulzar returned home before the festival started due to a feeling of "discomfort" after a visit to his birthplace and his mentor's grave. Shobha De, another renowned Indian writer, had to cancel her trip at the last minute due to a visa delay. There has been some speculation, however, about security issues and political motivations.

"I think it would be a terrible shame if the Indian writers who were going to be here aren't here," he said, "because I do believe that there is a opening up of India and Pakistan to each other — it is happening almost despite the entrenched right wing lobbies on both sides. I have an Indian publisher, I've collaborated on two movies with Indians, I have readers in India, I've travelled to India and Indian friends came for my wedding in Pakistan eight years ago. I have friends who are musicians and actors and they are all collaborating. I have friends in business and there are a lot of opportunities in business across the border for both sides."

"For all of us who believe that this ridiculously antagonistically divided sub-continent needs to heal itself, which every writer I can think of feels that way, these are great chances to do it. Not that necessarily suddenly the wall will tumble down because Shobha De is reading here, but many of the people here will never have seen an Indian pubic figure talk about anything in real life and if you have 15,000 people here exposed to that, then that matters. It also matters symbolically that people can see from India that their writer can come here and that they are treated with respect and admiration and they go back. It's a shame if it's not happening."

How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia is published in the United States on March 5 and in Pakistan and India at approximately the same time. It will be released in the United Kingdom on March 28.

Annie Ali Khan contributed reporting for this article.