Interview: Maggie Lemere and Zoe West on a 'Human Connection' to Burma

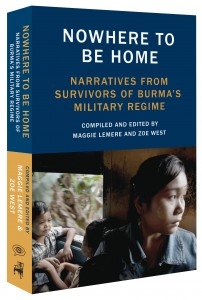

Twenty-three years after martial law was established in Burma (also known as Myanmar), the Southeast Asian nation remains one of the most repressive, isolated societies on Earth. Writers Maggie Lemere and Zoe West compiled and edited the accounts of 22 survivors of the Burmese regime into an extraordinary new book entitled Nowhere To Be Home: Narratives from Survivors of Burma's Military Regime. Through this oral history, readers catch a glimpse of what life is like for Burma's 50 million citizens, people who live under a regime noted for extensive human rights abuses.

This coming Tuesday, October 11, excerpts from Nowhere To Be Home will be read aloud at the Asia Society New York event Voices of Burma, by writers Amitav Ghosh and Deborah Eisenberg, actors Wallace Shawn and Kathryn Grody, Burmese dissidents U Agga and Law Eh Soe, and others.

Recently, Asia Society Online had the opportunity to discuss Nowhere To Be Home and Burma with Maggie Lemere and Zoe West.

What inspired you to use the oral history structure in telling the story of life in modern day Burma? What does oral history offer that other methods don’t?

There has been a lot of excellent and important human rights documentation done about Burma, but we believe oral history narratives add another valuable layer to our understanding of human rights crises.

The benefit of this book is that it is in the first-person perspective, and in the words of people from Burma themselves. Given that these stories have the space for a full life story, there is room to explore the grey area of the crisis in Burma, and to begin to understand these seemingly faraway stories at a very human level — instead of hearing about black and white statistics and about “victims,” we hear about people — people who describe facing challenges, abuses, and very difficult decisions, but who also talk about their childhood memories, their relationship with their parents, their marriage, etc.

We hope this book will help provide a general overview of the crisis taking place inside Burma and in its bordering regions — a crisis which has lasted for more than 50 years (it is often said that the civil war between the Karen National LIberation Army and the Burmese government military is the longest-running civil war in the post-WWII era). We might hear dire statistics about the myriad human rights abuses in Burma including the burning of villages in Eastern Burma and the approximately 140,000 people killed in Cyclone Nargis, or the brutal suppression of the 2007 “Saffron uprising,” that it can become difficult to relate to what is happening on any level. We hope this book will be another step toward people in the US and other countries building a human connection to the people of Burma, and striving to understand the situation in all its complexity. We truly believe that a real and sustainable path to peace is not possible without a deep understanding of the complexities and grey areas of the situation in Burma.

The people we spoke with were very determined to share their stories, and committed to do so in great nuance and fullness. Despite having faced many difficult experiences, the narrators spoke not only about the many things they wanted to see dramatically changed but also about the things they loved in Burma. They were very supportive of the project, and excited to share their voice in a space that allowed for a full life story.

What were some of the operational difficulties you encountered in collating the stories?

Because of the very challenging security situation inside Burma itself, we chose to do the majority of interviews in neighboring countries with people who had recently left. These people also faced very real security concerns — including lack of documentation, as well as concerns for their family back in Burma, who could be harassed by the government if they were identified in these interviews — and security was thus a strong priority for this project. Names were changed, names of places were removed, and any details that might identify narrators or their family and friends were removed.

Is there anything unexpected that you uncovered in the histories you recorded? What surprised you the most?

Although we became involved in this project in large part because of our belief in the importance of storytelling, our experience working on this book has amplified that belief even more strongly. The process of sitting for hours and hours to listen to people’s life stories is intense and utterly unique — at every step, we became aware of how much more there always was to learn; this is inevitable when you are listening to someone’s perspective in such depth. As we became involved with so many people and so many stories, we understood more deeply how dangerous it is to stick with a single narrative, especially when trying to understand entrenched conflict — how pivotal it is to accept complexities, no matter how much they challenge what you know. We both learned so many new details of the current and historical situation in Burma that challenged us to constantly add new layers to our understanding and analysis.

Will the transition to a civilian government in Burma lead to an improvement in the country’s human rights record? Or does it mean more of the same?

Although there are now more non-military players in Burma’s political fields, the military effectively retains full control of political processes.Since the transition to a civilian government, there has been much debate about whether the appearance of change and openness to debate is significant or superficial. At this stage, it’s difficult to say anything for sure — for example, whether the recent decision to halt the construction of the Myitsone Dam was made in the interests of civil society and the environment, was part of a power play, or was an attempt to appease environmental groups and Western governments. Although positive changes have been made in recent months, it is crucial to also note that some of the most overt human rights abuses — such as the more than 2,000 political prisoners, and the military offensives in eastern and northern Burma — continue. President Thein Sein seems to have been given more power than expected, but the situation — as well as intentions and motivations — is certainly fragile and unpredictable.

Do you feel that engagement with the Burmese regime would help open the country? Or should the outside world pursue a policy of isolation.

There is no easy answer for how to "fix" Burma or change the government there, and we would be very cautious about saying we have an exact answer about engagement. Any engagement must precisely aim at benefiting the citizens of Burma, not the generals. Engagement must not be an excuse to continue the destruction and sale of Burma’s natural resources at unsustainable rates, for example, and must be met with the continuation of real, progressive reforms on the part of the regime. Likewise, sanctions should be increasingly targeted at the generals and their cronies, such as their international bank accounts, rather than at the Burmese population as a whole.

Despite the difficulties over the question of engagement, we do believe there are important ways that people in the US can act in solidarity and support with Burmese people such as providing educational and basic living resources to refugees in refugee camps along the Thailand-Burma border, or helping to lobby our officials to pressure their counterparts in countries such as Malaysia, Thailand and Bangladesh to protect and ensure the human rights of Burmese migrants and refugees. The Burmese have hundreds of community-based organizations which they administer to help educate and support people in their own communities — they typically operate with a shoestring budget, and our support of them is crucial.

Voices of Burma event details

Asia Society Task Force report of Burma/Myanmar