Interview: Historian Investigates the 'Pity of Partition' Through Manto's Life and Writing

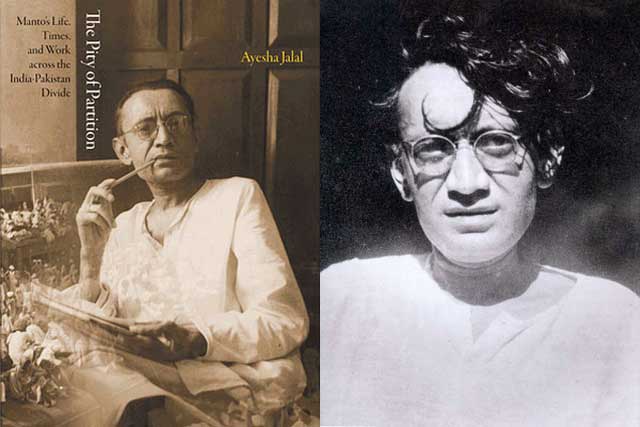

L: "The Pity of Partition—Manto’s Life, Times And Work Across The India-Pakistan Divide" by Ayesha Jalal (HarperCollins India, 2013). R: Saadat Hasan Manto (1912-1955). (Wikipedia)

The complex life and legacy of a major 20th-century South Asian writer are explored this week in Mumbai when Asia Society India Centre hosts a panel discussion on the still-controversial Urdu author Saadat Hasan Manto (1912-1955). Although most famous for his wrenching stories focused on the human toll exacted by partition in 1947, Manto left behind a large body of work that also includes radio- and screenplays and essays like the sardonic "Letters to Uncle Sam," written in the early '50s, that seem to presage today's endlessly fraught U.S.-Pakistan relationship by several decades.

Appearing in Mumbai on Thursday, July 18 will be historian Ayesha Jalal, whose latest book, The Pity of Partition: Manto's Life, Times, and Work Across the India-Pakistan Divide (published by HarperCollins India in India and Princeton University Press in the United States) uses Manto's life and work, in the publisher's words, "as a prism to capture the human dimension of sectarian conflict in the final decades, and immediate aftermath, of the British Raj." Joining Jalal are the distinguished Indian filmmaker Shyam Benegal and poet and journalist Jerry Pinto, whose book Bombay, Meri Jaan: Writings on Mumbai (co-authored with Naresh Fernandes), includes an exploration of Manto’s engagement with Mumbai.

Currently Mary Richardson Professor of History at Tufts University, Ayesha Jalal is perhaps best known for her first book, The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League and the Demand for Pakistan (1985), a groundbreaking study of Pakistan's founder. A specialist in the field of Muslim identity in South Asia, she also brings a personal interest to Manto's life and career, in that she happens to be the writer's grandniece.

Asia Blog reached out to Jalal just before her Mumbai talk.

In the early 21st century Manto seems to be enjoying a resurgence that exceeds even what we normally see when a writer reaches his centenary. He's the topic of panel discussions at South Asian literary festivals, a new movie about his life is in production, and BBC Urdu even just ran a feature story about his typewriter. What is it about his work and life that speak to our present moment?

Manto was a rebel and a contrarian by choice. He broached awkward social issues other writers scrupulously avoided in order to lift the veil of hypocrisy covering them. Despite the absence of state sponsorship, whether in India or Pakistan, Manto's works have continued to be widely published, discussed, read and performed across the subcontinent. The ranks of his admirers have swelled in recent times. His sensitive depiction of the violence unleashed in 1947 is internationally recognized as indispensable to discussions of the human dimension of partition.

As his writings are translated into English and other languages, Manto has been growing in stature. The trend will only grow as Manto's work become available via the Internet to a diverse and transnational readership. His bold choice of themes, whether on social duplicity, women's sexual exploitation and prostitution, criminality as a product of external ills or violence mistakenly attributed to religious passions, has a perennial relevance and explains Manto's iconic status among his enthusiasts.

A special attraction of your upcoming appearance at Asia Society India Centre is that your interlocutor will be Shyam Benegal, a major Indian filmmaker who has tackled any number of social issues in his work. Is it conceivable the two of you will turn your attention to Manto's career as a screenwriter — and does his work in the Bombay film industry figure at all into your study of Manto as a chronicler of Partition?

Yes The Pity of Partition: Manto's Life, Times and Work across the India-Pakistan Divide does deal with Manto's career as a screenwriter in the Bombay film industry. While it no doubt makes for an intriguing story, I can’t say at this stage that Shyam Benegal and I will collaborate on bringing that aspect of Manto's life to celluloid.

Your new book benefits from the special access you had to family papers and photographs. How does this material add to what was already known about Manto?

Your new book benefits from the special access you had to family papers and photographs. How does this material add to what was already known about Manto?

The family papers provided me insights into not only Manto's relationship with his mother and sister, but also with his large circle of friends. Read together with his own writings, these papers have helped me piece together the personal and public aspects of his life at a time of a great historical rupture in a way that I don't think has been done before, certainly in English.

In spite of Question #1, above, here in the U.S. Manto nonetheless remains frustratingly little-known, aside from "Toba Tek Singh" and the "Letters to Uncle Sam." For American readers who want to delve further into his work, what would you recommend they seek out?

You are quite right. There is just not enough of Manto that has been translated into English to familiarize American readers with the full scope of his corpus. I hope this will be addressed soon and efforts made to translate a larger and more representative part of Manto's writings, not just the short stories but also his sketches and essays. Until then readers in the USA should look for translations of Manto's work that do exist, for instance Hamid Jalal's Black Milk, Khalid Hasan's Bitter Fruit [also published as Kingdom's End: Selected Stories] and the bilingual centenary volume co-edited by me and Nusrat Jalal called Manto.

For anyone curious to learn more about Manto and Ayesha Jalal's work, Asia Blog recommends two installments of Another Pakistan, the podcast series presented by Asia Society in collaboration with Christopher Lydon and the Watson Institute at Brown University in Summer 2011:

Ayesha Jalal on Pakistan's 'Revenge of the '40s, Then the '80s'

Ayesha Jalal, Part II — What Would Manto Say?