Interview: Film Actress Wu Ke-Xi Reveals the Making of an Ordinary Myanmar Woman

Asia Society Museum’s history-making exhibition, Buddhist Art of Myanmar, opens February 10, 2015, in New York. Exploring Buddhist narratives and regional styles, Buddhist Art of Myanmar is the first exhibition in the West to focus on art from collections in Myanmar. Learn more

Some director/actor partnerships in film are so iconic that the individuals are inextricably linked in viewer imagination. Lee Kang-Sheng is inseparable from Tsai Ming-Liang’s world of loneliness. Setsuko Hara is the symbol of feminine resilience in Yasujiro Ozu’s domestic dramas. Denis Lavant brings an unmatched physicality to Leos Carax’s nighttime dreamscape. The list goes on. Muse and alter egos for their creative cohorts, these actors enliven the directors’ visions and bring an otherwise unthinkable identity and continuity to a body of work.

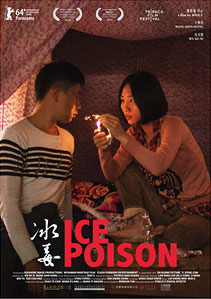

Having appeared as a Myanmar woman struggling for survival in two features (Poor Folk and Ice Poison) and two shorts (The Palace on the Sea and Silent Asylum) by Midi Z, the subject of Asia Society’s film survey Homecoming Myanmar: A Midi Z Retrospective, running from March 6 to 13, actress Wu Ke-Xi has become the face of the young filmmaker’s oeuvre. Along with acting partner Wang Shin-Hong, who, like the director, was born and raised in Myanmar in an ethnic Chinese community, Wu has brought soul to Z’s authentic portrayal of a people struggling on the margins of Myanmar society.

Whenever Wu appears in film festival post-screening Q&As around the world, audiences are shocked to see a stylish young woman with a cosmopolitan flair walking onstage. Unbeknownst to most, Wu was born and raised in Taiwan. Before meeting Z, she had never been to Myanmar. Blending in seamlessly with a cast of mainly nonprofessional locals, Wu woos the audience with her convincing transformation into an impoverished Myanmar woman from the countryside.

Wu found her calling in performance at an early age. She became a hip-hop dancer in high school and joined a theater group while majoring in Turkish in college. She has acted in television and commercials but it wasn’t until she met director Z that she was able to fully uncover her potential.

I had the pleasure of catching up with the actress via the Internet before her trip to Lashio — in eastern Myanmar, where Z is from — to experience, for the first time, Lunar New Year Myanmar-style.

(Note: In 1989, “Myanmar” replaced “Burma” as the official name of the country. Many Myanmar people still call their country “Burma,” as does Wu Ke-Xi in this interview.)

This spring, Asia Society New York presents Myanmar's Moment, a season of programming that will include talks, films, and performances exploring Myanmar’s past, present, and future. Learn more

How did you start working with Midi Z?

In 2009, I came across a Taiwanese cinema website created by independent filmmakers. Midi Z posted that he was looking for people to join his short film projects. That’s how we met. He always tells people we met “online.” It sounds so casual! [Laugh] When Ang Lee’s wife asked him how he met me, he simply said, “Online.”

He was admitted to the Golden Horse Film Academy organized by [film director] Hou Hsiao-Hsien. He had to make a short film and his producer thought of me. He contacted me for a simple audition, and we started working with each other. Back then, he made films set in Taiwan and I played a Taiwanese in two short films.

In 2010, Burma began to hold democratic elections. He thought about going home to shoot a Burmese story. He asked me to start to learn the language and prepare for a Chinese Burmese role. I began by learning the Yunnan dialect with Midi and [Wang] Shin-Hong.

How challenging was it? I understand that the ethnic Chinese in Myanmar don’t speak the standard Yunnan dialect.

It’s a little bit mixed with Burmese. I am familiar with learning languages, but [Midi and Shin-Hong] are not very good teachers, I have to say. [Laugh] They know how to speak but they don’t know how to teach. It was hard for me because I had to learn from them by listening.

You also spent some time with the Chinese Myanmar community in Taiwan.

I spent three months working in a restaurant washing dishes and waiting tables in order to learn the language. Midi wanted me to get rid of my urban persona. He asked me to do manual labor and to roughen my hands.

Did the people there know you weren’t really trying to make a living?

Of course not. I pretended to have been born in Lashio but had come to Taiwan at an early age; thus I couldn’t speak the language.

You also lived in Myanmar for a period of time before shooting the first film.

I stayed there for three to four months. The local people, up until now, still don’t know I am from Taiwan. I know how to dress like a local. I brought along my mom’s '80s-style clothes and imitated the way the locals behave. I really wanted to be their friends. I wasn’t there just to make films. They are very nice people with good hearts. I just stayed there and lived with them.

Were your dance and theater backgrounds helpful?

Very helpful. Because of my background in dance, hip-hop, I could quickly imitate the way people move their bodies in Burma. I could capture the body language of a poor woman in Burma quickly. With Midi’s films, we don’t get a screenplay. I was given a screenplay only once since I started working with him, none for Poor Folk, and none for Ice Poison. We improvised and received the director’s instructions on the set. I used my theater acting training and improvised.

How then did he plan a day’s work?

He has a clear structure in his mind but he wouldn’t tell us much. It’s very hard to shoot films in Burma because everything is uncertain. For example, people don’t show up on time. When we make a plan with a taxi driver to drive us to the mountains, he might not show up or he might suddenly demand more money. We are always solving problems. We also have to hide from soldiers and the police [for shooting without a permit]. Midi only tells me the day of what scene we are going to shoot and what we have to do. He usually tells me the goal of the scene, and my job is to achieve that goal.

'Ice Poison' (2014)

There are some very long takes. Did you rehearse ahead of time?

It depends. If it’s a scene involving a nonprofessional local, we don’t rehearse or rehearse very little. Since they are nonprofessionals, rehearsals scare them. So we just become friends. They like me and they are not afraid of me. My mom [in the film Ice Poison] shared a similar experience [with her character]. Her daughter was also sold to China. The director told us that in this particular scene, my goal was to persuade my mom I should stay in Burma, whereas my mom’s goal was to dissuade me from staying in Burma. We then started to shoot and improvise. We made about five takes. In one take, I failed to persuade her. It was very emotional and I cried. In another take, I yelled at my mom. In yet another take, nothing much happened. Usually Midi would choose the least dramatic take. [Laughs] As an actor, I always want people to see my dramatic side but he always chooses what he thinks is the most realistic. When it’s a scene between me and Shin-Hong [the male lead], however, we had some time to rehearse.

Does improvisation afford you more creative input as an actor?

Yes. That’s why I like this way of filming. The director, the crew, and I are very familiar with each other. We trust each other. I can really relax and follow my emotions. When I work with other directors, I don’t improvise since I don’t know if s/he would be mad. But with Midi, I could just very naturally create anything I want.

Can you tell me an experience in Myanmar that left a deep impression?

On the first day of the shoot for Ice Poison, we went to the mountain to meet a grandpa, who plays Shin-Hong’s father in the film. He’s very poor. We had an appointment with him to shoot some scenes at his house. When we got there, he was very sad and was smoking his water pipe. He told us that his oldest granddaughter was taken away by the kid he had hired to help harvest corn. Bride-snatching is a custom there. When a man wants or is in love with a woman, he kidnaps her and keeps her for a day. Then the woman will have to marry him. When a woman is away with a man for a day, it’s believed that she is unfit to marry anyone else.

When we arrived, the grandpa was very sad and said he couldn’t shoot the scenes that day. He had heard that the kid who abducted his granddaughter would bring his family and the girl in the afternoon to propose marriage. We comforted the grandpa and Midi decided to capture the whole event. The cinematographer was shocked. He’s from Taiwan. It’s his first time in Burma and it’s the first day of the shoot. He’s about to shoot a scene without knowing what would happen. Midi told me to act as a relative of the girl and Shin-Hong as one of the boy's. We improvised and captured the whole scene.

We got there at 4:00 am and waited until 3:00 pm, when three trucks arrived at grandpa’s house. 20 family members came with food, flowers, drinks, and candies. The granddaughter, who’s very young, only 15 or 16, came with the kid — just a kid! They knelt down, bowed three times, and finished the wedding. It’s a proposal and wedding combined.

I remember one thing clearly. It was very touching. The bride’s mother was crying and was very angry before the entourage arrived. She said the girl was too young and shouldn’t be marrying a guy like that. She said she raised the girl all these years and she’s supposed to stay home and make money for the family. She vowed to slap the girl’s face when she arrived. But when the girl arrived and knelt in front of her, the mother cried and accepted the wedding. It’s very countryside. It might happen in the '40s and '50s in Taiwan. I was there to experience the whole event and felt as if I took a time machine back to the '50s.

What happened to the footage, which evidently didn’t make into the film? It could make a nice short film.

It’s in Midi’s computer. If he has time, he can edit it. Dramatic things happen every day. Dramatic stories are told by neighbors every day.

And yet the director always chooses the most undramatic scenes to include in his films.

[Laughs]

What are your hopes as an actor?

I hope to act well, regardless of the nationalities of the characters. I wish to have opportunities to play a Taiwanese in the future. People all think I am from Burma. I spend a lot of time explaining I am not Burmese. Yesterday I met a [Taiwanese] director. She asked me what my plan was for the future. I replied and then she acted surprised, “How come you don’t have any accent?” After Ice Poison was released in Taiwan, Taiwanese people think I am Chinese Burmese. I began to explain and I think people are beginning to know that I am Taiwanese.

Wu and director Z will join Q&As following screenings at Asia Society New York on March 6 and 7.