Interview: Eric Liu on the Chinese American Dream and 'Hybrid' Identity

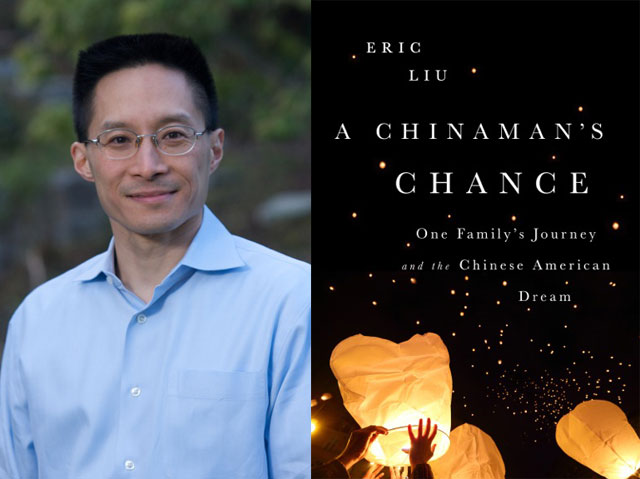

Eric Liu (L), author of "A Chinaman's Chance: One Family's Journey and the Chinese American Dream" (PublicAffairs, 2014). (Author photo: Alan Alabastro)

On July 29, 2014, at Asia Society's Northern California Center, Eric Liu will be discussing his latest book and the issues of citizenship, identity and the Chinese American Dream. The event is presented by Asia Society in partnership with the World Affairs Council.

What does it mean to be an American? What exactly is the Chinese American dream? In his most recent book, A Chinaman's Chance: One Family's Journey and the Chinese American Dream (PublicAffairs, 2014), Eric Liu unpacks the complexities of identity and citizenship, in a pivotal moment where China continues its ascent on the global stage and Chinese Americans are labeled with the term "model minority."

Liu is deeply interested in issues surrounding citizenship and civic leadership. As the founder and CEO of Citizen University, he seeks to investigate and foster a culture of citizenship, and the variety of embedded values, systems, and skills it entails.

Next week at Asia Society Northern California, Liu will discuss the nuances of Chinese American identity today, in all of its hybridity, fluidity and complexity.

In advance of his Asia Society appearance, Asia Blog talked to Liu via email.

For the last decade, Asians have been the fastest growing population in the nation. Asians also make up the largest college graduate population, earning the "model minority" moniker. What pitfalls or barriers are embedded in this model minority stereotype?

The model minority stereotype is an instance of what I'd call "damning by high praise." Though it's certainly less overtly noxious than some stereotypes, it is regrettable in at least two ways: First, it obscures the fact that the Chinese American and Asian American communities are not monolithically educated and economically secure; indeed, they are more like "barbell" communities, with many in deep and often multigenerational poverty who are often overlooked. The second way the stereotype is of course harmful is that it implies that other minority groups — African Americans and Hispanics in particular — are by contrast less-than-model. It's a usage meant to divide, even when praising, and that's why it needs to be called out.

How do you define the Chinese American dream, and how does it differ from the American dream, or the Chinese dream?

The Chinese American dream is a variant of the American dream that focuses less on material success than on a remaking of the culture of this country. It is the dream of being able to claim this country — America — and to redeem its promise of opportunity in a way that doesn't require a WASPifying assimilation but rather embraces all the styles, values, and mindsets that families of Chinese ethnicity can bring to the culture. In this age of global flux, when China is rising and America worried about relative decline and the diminishment of opportunity, the traditional American dream may seem in danger.

But in my view, the United States retains an inherent competitive advantage, which I summarize this way: America makes Chinese Americans; China does not make American Chinese. And so while China's leaders today may speak of a "Chinese dream" of harmony and prosperity, their society is ultimately less resilient and adaptive than the America's is — potentially. One measure of whether we fulfill or squander that potential is whether Chinese Americans find that their best field of opportunity in this age is America and not China.

What issues do you take with the term "Chinese American," and why?

I don't hyphenate Chinese American. I treat American as the noun; Chinese as the adjective. Or as one of many adjectives. This is not just a grammatical point. To me, the hyphenated form is wrong because it signifies an interaction between parties or nations rather than a person. So "Chinese-American diplomacy" or "Chinese-American trade" makes sense to me grammatically. But when talking about myself and others in this country of Chinese descent, I leave behind the hyphen.

In your latest book, A Chinaman's Chance, you write about realizing that identity wasn't a matter of personal choice but one of what you call "cultural inheritance." What are some examples of this inheritance?

The inheritance takes so many forms in my own life. Some are easily perceptible, like my partial command of the Chinese language or my palate and my taste for Chinese stir-fry. Others are more subtle, like my Confucian focus on webs of relationship and obligation, my communitarian idea that every right bears a responsibility, my contextual awareness of history that puts rugged individualism in proper perspective. These are all things that have become clearer as I have grown older — and especially as I've gone deeper into fatherhood.

What are some of the challenges of having a dual identity? How have you personally grappled with combining two very different cultural experiences?

I don't believe I have a dual identity. I have an identity that draws from two great sources whose waters intermingle. This is not "the melting pot" and it is not being "divided against myself." It is about inhabiting the hybrid in a way that is Chinese in its particulars but universally American.

What does it mean to be Chinese American today, and how do you think your experiences might compare to that of future generations? What potential changes are you optimistic about?

To be Chinese American today is to be the embodiment of the hopes and fears that attend China's arrival. It is to simultaneously claim this country's culture, politics, and public life in ways that were barely imaginable a couple of generations ago — while also guarding against the longstanding presumption in American life that we with Chinese faces are to be presumed foreign until proven otherwise.

For future generations, starting with my own daughter's, I believe that the hybridity, fluidity, and complexity of identity will only increase in America. She and her peers will define Chinese American in new ways. And I see that not as loss or threat but as the very wonder and purpose of American life. We preview for the rest of the world what it is like when bloodlines and memes and styles mesh.