Interview: Engineer John Godfrey Recalls 'Creative Collaboration' with Nam June Paik

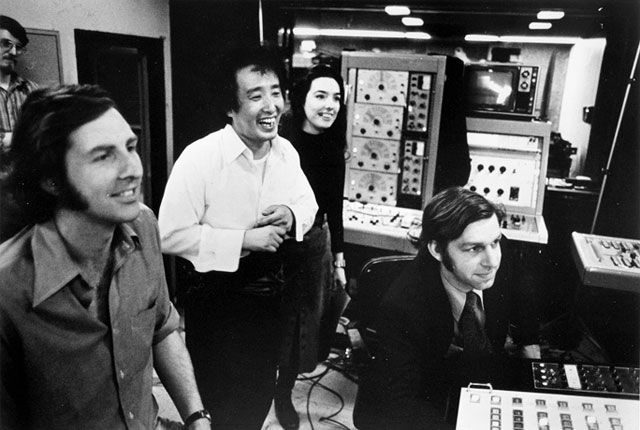

L to R: David Loxton, Nam June Paik, Charlotte Moorman, and John Godfrey at WNET's TV Lab studio in New York City. (Courtesy Howard Weinberg)

Asia Society Museum's exhibition Nam June Paik: Becoming Robot, on view in New York through January 4, 2015, focuses on the artist whose work melded technology, fine art, and popular culture. Learn more

A key area of focus of Asia Society Museum's current exhibition Nam June Paik: Becoming Robot is the artist's involvement with Television Laboratory (TV Lab), the experimental division of public television's Channel WNET/THIRTEEN in New York City from 1972–1984. In its 12-year run the TV Lab was a crucible for the development of video as an art form, giving a platform not only to Paik but to other pioneers of the medium such as Bill Viola and Ed Emshwiller.

As the TV Lab's supervising engineer, John Godfrey played an essential role in helping these artists realize their visions, and he even shares a joint credit on one of Paik's most important works of the period, Global Groove, from 1973. Groundbreaking both in form and content, Global Groove is an exhilarating 28-minute stream-of-consciousness tour through "the video landscape of tomorrow" that encompasses pop music (Mitch Ryder and the Detroit Wheels), the avant-garde (John Cage), and hypnotic abstract imagery along with advertising (in this case, a Japanese Pepsi commercial). Seen today, Global Groove is an obvious precursor to the music video genre and also strikingly prescient of other 21st-century phenomena we may take for granted, like channel-surfing and mash-ups.

Godfrey's reminiscences of collaborating with Nam June Paik are included in the catalogue that accompanies Nam June Paik: Becoming Robot. Just before the exhibition's opening, he expanded on those remarks in the following email interview with AsiaBlog.

You were a speech and drama major in college and a few years later you were helping to pioneer video as a new artistic medium. How did you come to be the head engineer at the TV Lab?

Ever since my father bought a TV in 1949 (I was six) I wanted to be involved in television. When it became time to attend college, he talked me into choosing electrical engineering (his Masters) and so I entered Purdue to study it. After about two to three years of "plug 'n' chug" I transferred for a year to Indiana University to their TV school and took all the courses I could in television.

I went back to Purdue to take all the garbage credits I needed for a degree in Speech and Theater; then decided to go back to IU for a Master's and, hopefully, avoid the Vietnam War.

I called up their tech director, who taught film journalism, and asked if there was a job I could do. He hired me to be the tape duplicator for two services that were just starting at IU — ETS/PS (Educational Television Stations/Program Service), which became the PBS library, and NCSCT (National Center for School and College Television, later called National Instructional Television). So it was me and six 2" videotape machines working from 11:00 at night to 7:00 in the morning. Such programs as the original 100 episodes of Mister Rogers' Neighborhood in black and white, sponsored by Sears. I realized that I was watching the master tapes, but I had to make sure that the copies I made were just as good because that was what the stations were broadcasting. I developed a method for how to set up a 2" machine to conform to the differences in tape to make a nearly perfect copy.

I rejected eight out of ten shows for technical quality from WNET. They sent their Chief of Technical Standards to Bloomington to find out what the problem was. I showed them and got hired to work for them in New York in 1969.

In three months I was promoted to Tape Supervisor, and started editing programs. There were some experimental shows going on and I was asked to see if I could find a way to get un-airable ½-inch videotape to broadcast quality. I did. And when the TV Lab under David Loxton was created in 1972, I was promoted (by now-WNET/THIRTEEN Chief Engineer Mal Albaum) to be the engineer in charge of their facility over at the Carnegie Building at 46th and 1st Avenue. It was an old black-and-white studio that wasn't (supposedly) usable for color. I had a budget of $50,000 to set up a studio and taping facilities.

Global Groove is a major Paik work on which he shares credit with a collaborator. Can you describe what your respective contributions were?

Paik, I believe, realized that to get things done well in a union shop, you had to work with the person(s) who knew the equipment. He saw that I enjoyed trying new things and that it would indeed be a creative collaboration rather than just him directing an engineer to push buttons. I came up with the mixture of images using the Grass Valley switcher we got for the Lab and integrated it with the Paik-Abe Video Synthesizer.

He was always complimenting me with, "... genius ... genius. ..." Of course, he said that of everyone he worked with.

Another way Global Groove seems ahead of its time is its matter-of-fact multiculturalism — Korean and Navajo musicians perform side-by-side with Beethoven and "Take Me Out to the Ball Game." Can you shed any insight into what drove Paik's musical choices in the piece?

I have always said of Paik that if you wish to know the truth in what he's saying, dig under the video art and look at the comments he's making. This is true of his mixture of genres.

With the benefit of hindsight, the TV Lab seems remarkable both because it was a high-water mark for adventurousness in public television and because public and private funding went to such wildly, and consistently, experimental work. Did you and your colleagues ever have a sense, at the time, of what a unique position you were in?

Only when looking back at the loss of it. I was so involved with all of the artists and trying to make their presentations unique that I did not really realize its impact. My wife at the time, Ruth Bonomo, did realize the uniqueness of the programming from the other fare of the station and that during 1976, over 70% of the original programming coming from WNET was from the TV Lab.

For anyone who wants to learn more about Nam June Paik, John Godfrey, and their work at TV Lab, Asia Society New York screens Howard Weinberg's absorbing new documentary Nam June Paik & TV Lab: License to Create, on Wednesday, October 22. Click here for complete details and ticket information.

Global Groove will be screened at Asia Society New York on Saturday, November 1 as part of the program "Nam June Paik: Video Across Media." Click here for tickets and complete program details.