Interview: From Brothels to Beards, Bangladeshi Photographer Captures the Human Spirit

In 1996, Bangladeshi photographer GMB Akash discovered he had a gift for connecting with his subjects through a camera lens. That discovery, coupled with life in a developing country full of millions of impoverished people and abused children, compelled him to take action and give voice to the voiceless through photography.

As he pursued his career, he came to the realization that simply reporting the human rights injustices through his photographs was not enough. He kept asking himself, "What changes have my photos brought to the lives of my subjects?" He knew that as a photojournalist, it was his duty to tell the truth, but as a human being he believed it was his moral duty to find ways to alleviate the exploitation and poverty his subjects were suffering. That's when he decided to photograph those he calls "survivors" — people in Bangladesh whose lives are a constant, daily struggle. These photographs led to a self-published photography book of the same name depicting the invincibility of the human spirit to survive against all odds. The proceeds from the book and subsequent exhibitions go towards helping the "survivors" by setting up small businesses that Akash trains them to run. Akash's photography has won more than two dozen awards from countries and organizations around the world over the past decade.

Asia Blog caught up with Akash to learn about his process and find out what he is working on next.

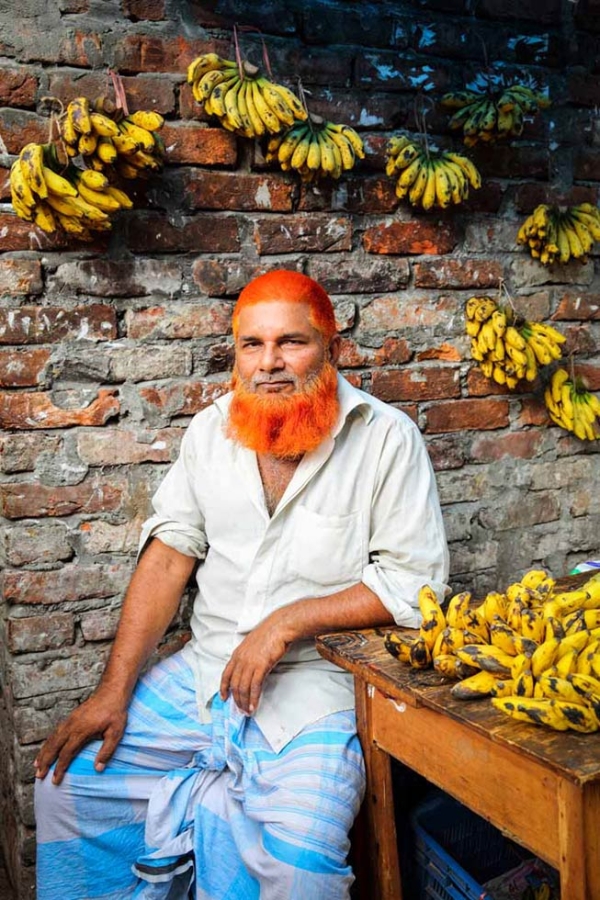

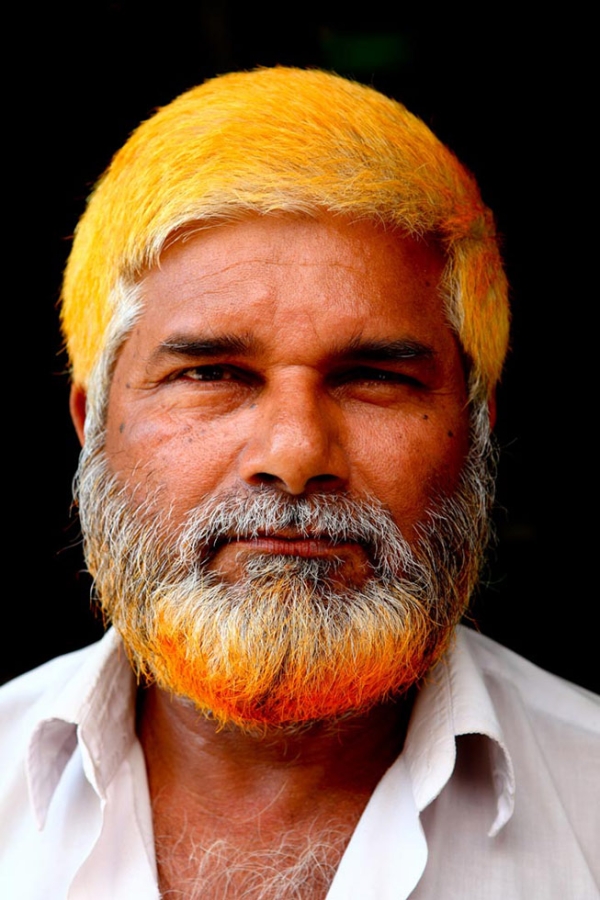

Your portfolio spans a variety of topics including child prostitution and mental disability, as well as slice of life pieces like the henna-dyed beards. You are often the first photographer to document these stories. How do you find them?

My photo journey compels me to discover the smallest pleasures of life that I was never aware of. Thus, seeking humanity around me is an everyday learning process. My thirst to discover something new helps me grow my vision for a new story. I can consistently work in one place, on one subject for a whole day. I believe every photographer should develop their senses in order to more deeply explore their subjects and the images that result from them. Many things inspire me. It can be beautiful colors, wonderful light or unusual compositions. But the main inspiration lies in my heart. The moment I feel something tug at my heart is the moment that enflames me the most.

Many of your photo essays suggest you spend considerable time with your subjects. How do you get such in-depth access? Can you describe your process?

With every picture you take, you enter into a space that is unknown to you as a photographer. In the beginning it feels like forbidden territory; a place you are not supposed to enter surrounded by borders of privacy you are not supposed to cross. You, the photographer, are there at a factory, an old peoples’ home or a brothel with your simple black bag hanging from your shoulder, eyeing everything around you as you are being eyed by the people there. The first days following these intrusions, I never take pictures because they would not be good. I wouldn’t know the people I met nor understand the place I had just entered — my photography would be bland and meaningless. There is always that moment when it feels completely natural to open that bag. But there is also no way of telling why that moment comes when it does. Suddenly, I have a friendly conversation, or the afternoon light makes everybody around me relaxed and mellow, or someone looks at me in a trusting and familiar way.

Then I take out my camera and for me and everybody around me, it is the most natural thing to do. There is consent. People don’t accuse me, or reject me, or pose in unnatural ways. They are just there, doing what they normally do. Then I click away, and it feels like a conversation — a conversation between me and the people, between me and the location, between me and the light, between me and the souls that make this place alive. In such moments, a landscape becomes a soulscape.

After such moments, life where I am working becomes trivial again. The next day everybody asks for their photographs. There is no difference whether the people are girls from a brothel, children working in a factory, or farmers from the countryside. But these little exchanges bring us closer to each other and strengthen the ties between us. It starts with small talk and conversation and continues with the first pictures I took. The relationship will begin to become deeper and more meaningful, as will the pictures I take. The closer I get to them and the deeper our friendship becomes, the simpler my photography gets. I am no longer looking for special angles or artistic points of view. I just open myself up to these people, take a good look, frame, and wait for the right moment.

GMB Akash.

What inspired you to do a photo essay on henna-dyed beards?

I have grown up in Bangladesh as well as in a Muslim community where a henna-dyed beard is very common. Besides the religious perspective, it is very interesting that the older generation has adopted this as a kind of fashion. They want to look good and younger. In addition to this, bringing out the cultural aspect of this practice was my motive behind doing the story. I wasn’t 100 percent sure of the basic reasoning behind henna-dyed beards. I only knew that the older generation of my country love to do it and they are noticeable everywhere. But what is the reason behind that practice? A few of my friends who came from Europe to travel in Bangladesh questioned me many times about this. To know the reason behind the older generation's particular affection for henna-dyed beards, I decided to do an investigation and the photo series.

Of all the stories you have covered over the years which photo essay was the most challenging to capture?

It is always challenging to be able to articulate the experiences of the voiceless and bring their identities to the forefront, which gives meaning and purpose to my own life. When I cover extreme social stigmas, I feel an urge to deliver those untold stories to the world’s table and to ask the people to walk up and see. My deepest personal concern is to get to the root of the situation, whatever it may be. I continue to work with the hope that I can bring possible changes.

The most challenging project was Life for Rent about sex workers. I put my endless passion into the stories, which were heart-wrenching. Getting access to the sex workers’ door and depicting their lives truthfully was the hardest part. Gaining access to these stories, building trusting relationships with these girls and everything else was very challenging. When I was able to be one of their companions with whom they could share their truth and their lives, I could use my camera and continue to focus on them, which enabled me to accomplish the project. Readers can get a glimpse of my work and my feelings during the work that I depicted in my blog post Life for Rent.

Where will your camera take you next?

I am an erratic type of traveler. My camera takes me to the places my heart desires to go at an unspecified moment in time. I am currently focusing on continuing my work on my Angels in Hell series that is based on child labor. In 2013, I established First Light Institute of Photography with the mission to provide training and education to unprivileged children in society. The school organizes various types of photography workshops for aspiring photographers at reasonable tuition. It also offers other activities including visiting photographers from around the world that contribute to the funding of our mission. Furthermore, I will be giving two photography workshops this year outside of the school; one in Italy and one in India.

Before long, I plan to publish my Angels in Hell photo series in the form of a book and try to use it as a source of continual funding for our underprivileged children’s education. We believe that when many small people in many small places do many small things, they can change the face of the world.