For China's New Leaders, the Spirit of Deng Remains Strong

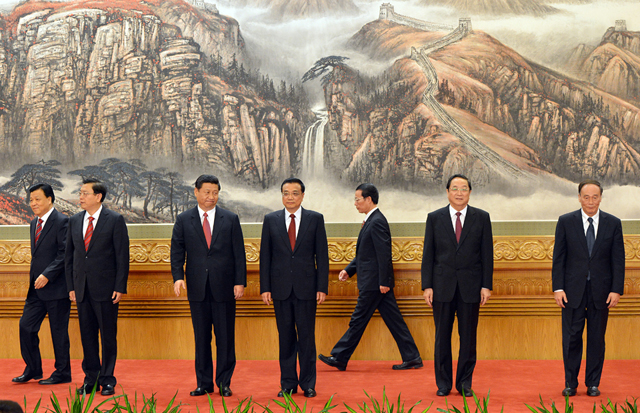

The new Politburo Standing Committee members (Xi Jinping, 3rd from left) meet the press at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on November 15, 2012. (Mark Ralston/AFP/Getty Images)

When China’s top seven new leaders stood in a row, in dark blue suits and ties, their appearance was almost indistinguishable. The attendees at the 18th Party Congress all clapped as the leaders laid out their goals for the years ahead. But behind the display of unity to promote socialism with Chinese characteristics, a peaceful rise, and the welfare of the Chinese people, there were many different views about how to get there. Among Chinese concerned about national policy, inside and outside the Communist Party, one can detect at least four major perspectives: 1) Maoism, 2) rule-based liberalism, 3) assertive patriotism, and 4) Dengism.

Maoism

No one advocates a return to the mass mobilization and large-scale collective projects of Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward. Some protesters demonstrating against corruption and unfair treatment may draw lessons about how to attack officials from Mao’s Red Guards, but no one calls for a return to the revolutionary violence of the Cultural Revolution. At the mammoth Historical Museum adjacent to Tiananmen Square, displays from the period of the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution are nowhere to be found.

But many workers in large enterprises, who in Mao’s days enjoyed high prestige and lived more comfortable lives than most Chinese, are upset that the working class no longer enjoys such prestige and special privilege and that businessmen and officials who milk the system for private gain live much better than the average worker.

Many who long for the Mao period romanticize the simpler, purer life they once enjoyed, when people were not so selfish in pursuit of wealth and were willing to do more for the community. They tend to forget the corruption of the Mao period, when officials lived better than ordinary people and tattlers reported on others for personal gain. Some, like former peasants who moved to more complex urban environments, wax nostalgic about the good old days.

But in truth, few would trade their lives today — workers are no longer on the verge of starvation or terrified of political criticism, and they are hopeful that their lives will continue to improve. The public collective memory of Mao was long ago commercialized with the sale of Mao memorabilia, reflecting the triumph of markets over Mao’s ideology.

The public display of Mao’s thought remains weak. Just as the followers of Chiang Kai-shek hope his ashes will someday be buried in his native Zhejiang, so some officials are discussing taking Mao’s body back to his native village in Hunan to join his ancestors. For those who want to reduce Mao’s presence in the center of Beijing, the reunion of Mao with his ancestors offers an acceptable rationale even for Maoists, while avoiding a major split in the Party. In short, Maoism may have a future in song and poetry, even in nostalgic memories, but not in political policies.

Rule-Based Liberalism

Some older liberals who advocate greater freedom and more rights for all citizens are even more outspoken than younger ones — as retirees they have no fear of losing their jobs. Some of these older liberals remain bitter, several decades after the suffering that they or their friends and relatives were subjected to for speaking out, displaying insufficient enthusiasm for party policies, or simply being branded as a member of the bourgeois or landlord class. Since 1978, as university education and foreign travel exploded, older liberals have been joined by even larger numbers of young liberals who believe China should now reduce the role of censorship and state security officials who restrain the freedom of public expression.

Some Chinese citizens, especially those trained in law, believe that leaders, as well as ordinary people, should be subject to the rule of law, that laws on the books should be fully implemented, and that clear and fair procedures should guide the process of deciding whether an individual has violated the law. Many citizens seek protection from officials who attack them or appropriate property without paying adequate compensation. Some able young Chinese who have lived abroad seek the same freedoms and access to information as residents of many foreign countries enjoy. Today, even many who are unaware of legal issues resent the constraints on their freedom. Many of the hundreds of millions who now use the internet resent it when the websites they want to visit are no longer available to them.

Of those who challenge the limits of freedom and the arbitrary exercise of power, many are likely to be constrained and even punished, as in the past. However, the appeal of those who want more open access to information and diverse views and those who want predictable rules and procedures constitute very powerful pressures on high-level officials trying to keep order. These pressures continue to grow.

Assertive Nationalism

For decades, the Chinese public has been flooded with accounts of the humiliation Chinese suffered at the hands of countries that invaded and exploited China, killing Chinese and ravaging the country, serving the interests of foreigners at the expense of Chinese. Now that Chinese GNP is likely to surpass that of the United States in the next few years, China has more foreign currency than any other country, and most countries trade more with China than with the United States, Chinese people feel that their country, with its long history and great civilization, has finally stood up and deserves to be treated as a great power.

Nearly all Chinese want to find positive ways to display their country’s prominence. They are proud of holding a spectacular Olympics, erecting ultra-modern buildings, establishing the world’s largest high-speed rail network, and launching communication satellites. They are now ready to communicate their successes to the world through CCTV, newspaper inserts, Confucian institutes, and invitations to hold conferences in China.

Some Chinese think that their country should now do more to assert its interests around the world. They support building a modern military, one that can match that of the United States. Should China not press the United States to reduce sales of weapons to Taiwan? Should it not be more assertive in expressing China’s position in its territorial disputes in the South China Sea and in what it calls the Diaoyutai islands?

Thus far China has criticized the United States for sending troops into other countries to impose its will on sovereign states. But China is building a stronger navy that can represent its interests in distant seas. Some specialists at Chinese think tanks, military leaders, and ordinary netizens not only urge the country to be bolder in standing up to foreign countries but to be prepared to attack islands it claims as its own, even if it runs the risk of conflict with Japan and other states. While foreign countries have become more edgy about Chinese military advances and territorial claims, citizens at home expect the government to be more assertive.

Dengists

Deng Xiaoping, beginning in 1978, set the guidelines that still govern today’s China. These include:

- Undertake reforms step by step;

- Open the country to ideas around the world and send people abroad to learn not only modern science and technology but the best management systems;

- Upgrade the educational system;

- Select people by merit and, as they prove themselves promote them, level by level;

- Develop good relations with other countries, especially the major powers, to access the best ideas; expand trade and domestic civilian investment so China can avoid the Soviet error of exhausting the nation to maintain military power;

- Give teams of leaders at each level the freedom to experiment and make bold changes that improve the economy and keep order;

- Expand the range of freedom, but minimize risks that would disrupt public order;

- Keep a unified Communist Party leadership at the top that allows the highest leaders to make decisions about what is good for the country, and do not constrain the top leaders by giving independent power to a separate judiciary and legislature; and

- Do not be constrained by ideology, rather continue adapting and reforming as new conditions arise to benefit the Chinese people and strengthen the nation.

Shortly before he took power, Deng visited the border area near Hong Kong, the “southern window” through which new ideas and experiments would come. On his first trip after taking power, Xi Jinping went to that border area near Hong Kong, Shenzhen, in Guangdong Province where his father, Xi Zhongxun, served as provincial party secretary under Deng just as China began its bold experiments in reform. In Shenzhen, Xi Jinping laid a wreath at the statue of Deng, signaling his support for continuing Deng’s reform and opening.

Conditions in China are different than when Deng was in power. The nation is stronger and people at all levels expect China to expand its global role. Economic growth that thrived as Deng’s reforms yielded fruit must now adapt to new conditions. Recently, large investments in infrastructure and heavy industry have fueled growth, but new patterns of growth require more emphasis on expanding consumer spending, raising levels of technology, and moving industry inland for lower costs. Many officials who led rapid growth have found so many opportunities to divert public funds to enrich their families that the Chinese public is inflamed by their corruption.

A cynical public is less likely to listen to the voice of government officials and despite clampdowns, public discipline in following official guidance is weaker than it was under Deng. A far better informed public is no longer content to accept simple government propaganda, especially when it departs from their understanding of reality. Contacts with foreigners are so widespread that the flow of foreign information and ideas cannot be slowed down.

It is not possible to predict in detail what Xi and his team will do over the next decade. They may face more internal protests, economic problems, or foreign assertions of power that will require new responses. But thus far the signs suggest that they will continue Deng’s efforts to keep a meritocratic experienced Communist leadership at the top, without great changes in the formal structure.

The new Chinese leadership team is likely to continue trying to avoid conflict with other powers and extend China’s role in international organizations. They are likely to continue reforms, from leading those who got rich first to helping those who are not yet rich. They will endeavor to strengthen the national welfare net. They are likely to take bolder action against corruption than their predecessors, even if it risks resistance from the family and friends of those being attacked or frightened of being attacked.

They are likely to try to extend the freedom of journalists and netizens to criticize not only the lowest level leaders but leaders at somewhat higher levels — though they are unlikely to allow public criticism of the highest levels of power. The new leaders will support the expansion of Chinese firms going abroad and will strengthen the news media that express Chinese views directly to foreign publics. They will continue initiatives to expand renewable energy sources while the consumption of coal and gasoline expands.

In short, the spirit of Dengism is likely to remain strong, especially at the highest levels, trumping all the other perspectives as the leadership team endeavors to continue Deng’s successes in strengthening the nation and improving the living standards of their people.

Ezra Vogel, author of Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China, received an honorable mention in this year's Bernard Schwartz Book Award.