China v. Japan: Three Questions, and a Sea of Anxiety

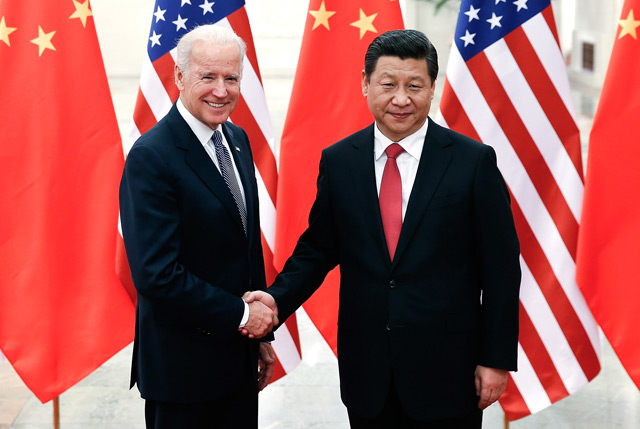

Chinese President Xi Jinping (R) shakes hands with US Vice President Joe Biden (L) inside the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on December 4, 2013. (Lintao Zhang/AFP/Getty Images)

Visit Asia Society's ChinaFile site for this related content: "What Posture Should Joe Biden Take Toward A Newly Muscular China?," "Why’s the U.S. Flying Bombers Over the East China Sea?," and "Chinese Netizens Applaud Beijing’s Aggressive New Defense Zone."

Could the world's great powers really come to blows over a handful of rocky, uninhabited islands?

For some time the answer to that question has been, basically, "Of course not." The tough talk from China and Japan was bluster, meant for domestic consumption; cooler heads would surely prevail; the economic stakes for both countries were far too high to imagine a different outcome.

Today, however, the answer is less clear, and a diplomatic scramble is underway — as serious and complex as any on the globe today — to ward off conflict over those tiny islands. In the last few days alone, China has charged Japan with aggression, Japan has vowed it will "not tolerate the attempt by China to change the status quo by force," and U.S. Vice President Joe Biden, on a difficult tour of the nations in question — said China had "raised regional tensions and increased the risk of accidents and miscalculation."

Those risks have risen sharply, following China's late-November announcement of an air defense zone over the waters in question. "Beijing has upped the ante, and it's getting way too hot in the region," former U.S. Ambassador to China Jon Huntsman told the BBC this week. On Chinese television, it has been hard to escape the story — with the various renditions of the new Chinese maritime map, strident defenses of the Chinese position, and dire warnings of what may happen should Japanese planes challenge the zone. Huntsman is right — it's "getting way too hot" — and there is no obvious path to a cooling of tensions.

How did we get here?

In large part, the answer to that question involves growing nationalism in both countries: with economic success and a confident new leader, China has become stronger and more assertive, just as nationalist sentiment rises in Japan. Professor Shen Dingli, associate dean at Fudan University's Institute of International Studies — and a member of Asia Society's Global Council, warns that one nation's hard-line approach only begets another's, producing an increasingly dangerous cycle. At nearly every turn, says Shen, "the two countries are making each other more nationalistic."

The dispute itself is not new. Japan has claimed the islands (it calls them the Senkaku; in China they are the Diaoyu) for decades, and the Japanese declared an air defense zone of their own in the area more than 40 years ago. Last year the government of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe effectively nationalized the small chain, and since then China has sent ships and aircraft to the region, a series of small probes and provocations that culminated in its air-defense demarcation last week. The Chinese lines overlap the Japanese — and so for all the niceties from Beijing (a spokesman called it "a zone of cooperation, not confrontation") that gesture has been the most provocative to date. All of a sudden, we have an almost Cold-War-like showdown that involves the superpowers of East Asia.

There are other players in this dangerous game. The U.S. is walking a diplomatic tightrope, seeking to manage an ever-delicate relationship with Beijing while pledging to honor treaty obligations to defend Japan. So while President Barack Obama dispatched B-52s to the disputed airspace (a tough message to China), the U.S. also asked its civilian air carriers to report any incursions to the Chinese (seen as a win for Beijing). Korea is involved, because the Chinese zone crosses Korean-claimed airspace as well. And to the south the nations of ASEAN, many of which are already challenged by Beijing in the South China Sea, worry that China will soon mark out a similar air defense zone over those disputed waters.

What's needed are trust-building measures, military-to-military hotlines, reassurances that no side will further provoke the other, and perhaps some clear reminders of the dangers. The Cold War had the latter, in extreme form; Moscow and Washington knew well that miscalculation and provocation could take both superpowers to nuclear armageddon. In the current situation, absent any of the above, the provocations pile up, and the fear grows. Tokyo's fundamental position is that there is nothing to discuss. The islands belong to Japan. And China shows no sign of flexibility. As Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs Liu Zhenmin, writing in China Daily, warned this week, There must be no "provocations against China's basic principles"; China's recent actions, he said, are "legitimate exercises of its jurisdiction over these islands."

So what is to be done? And what realistically can be done?

For those with good answers to those questions, a Nobel Peace Prize awaits.