Book Excerpt: 'Tremors: New Fiction by Iranian American Writers'

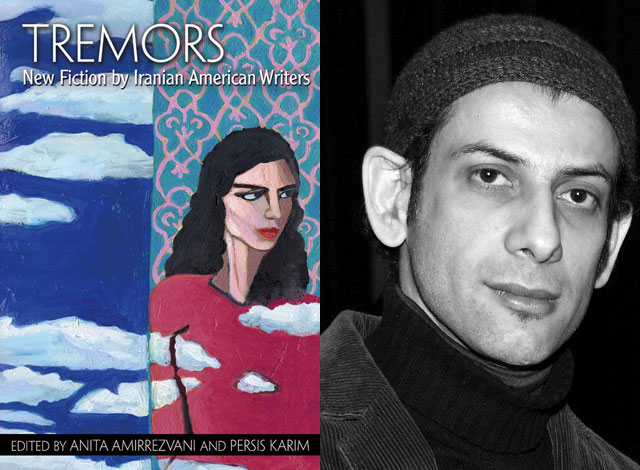

"Tremors: New Fiction by Iranian American Writers" (University of Arkansas Press) includes a short story by Salar Abdoh (L). (Courtesy the author)

Recently published by the University of Arkansas Press, Tremors: New Fiction by Iranian American Writers is a wide-ranging anthology that surveys the diversity of Iranian American experience through the work of 27 authors. On Wednesday, December 4, the book's co-editors, Anita Amirrezvani and Persis Karim, are joined at Asia Society New York by their fellow writers Salar Abdoh, Dalia Sofer, and Nahid Mozaffari for a panel discussion that will touch on, among other topics, the role of fiction vs. memoir and poetry; the differences between literature being written in Iran and the United States; and the connections between tradition and the minority experience. Amirrezvani will also discuss and sign her new historical novel, Equal of the Sun.

"Fixer Karim," below, is the contribution to Tremors by Salar Abdoh, author of the novels The Poet Game (1999) and Opium (2004). His new novel, Tehran at Twilight, will be published in 2014, and Abdoh is also editing the anthology Tehran Noir for Akahsic Books (forthcoming). Currently an Associate Professor in the English Department at The City College of the City University of New York, and Co-Director of the MFA program in Creative Writing, Abdoh divides his time between Tehran and New York City.

Asia Society Museum's landmark exhibition, Iran Modern, which runs through January 5, 2014, in New York, focuses on Iranian art created during the three decades leading up to the revolution of 1979. Learn more

"Fixer Karim"

By Salar Abdoh

I knew the guy they called Heavy K from back in Tehran. He spoke perfect English, but twisted it with an Australian accent, which was strange, endearing, and maybe even a bit sinister when you got to thinking about it. I always imagined that all those language CDs he'd listened to for his pronunciation had been created by some underground guerilla Australian outfit whose goal it was to disseminate free-of-charge Aussie-accented English across the Middle East. K, whose real name was Karim, was what you might call an operator. Tehran got hit periodically with bursts of foreign journalists, the same way Baghdad and Kabul did. And for times like that K had made his services indispensable. His official job was as a fixer and a translator. He had his list of contacts in various ministries. A journalist could arrive in Tehran on a late Sunday evening and leave on an early Tuesday morning and still manage to concoct an analysis of the latest student demonstrations or government roundup of opposition figures with some apparent expertise. Why? Because K was your man. Besides his ministry contacts, K also had sets of civilians on call for his clients. They might be shopkeepers or painters, butchers or motorcycle mechanics. It was these people's job to give finely honed sound bites, to summarize in one sentence where they thought the country was heading and why.

So there was efficiency to the way K did things. You had to admire him for that. He had ambition. Though I was never quite sure what that ambition was until he had already made a name for himself as a video artist and managed to procure an American visa and move to New York City. That was where I saw him on a bitingly cold January evening at a party. If he was surprised to see me there, he didn't show it. Nor did I.

"Nader, you devil," he said in that Aussie-accented English, "you finally got a free ride on the wings of that heiress back to America."

"Life is short, brother. We do what we can. You of all people should know that."

"Hear, hear!" He eyed the silhouettes of the guests loitering near the dark bar, the women mostly in black, the men casual and sporty. It was a loft downtown, and the two of us were both newcomers to the city, both of us glaringly out of our elements. I could tell by the way we hovered in a corner and hung onto each other like life vests. I'd grown up a good part of my life in California and then gone back to the Middle East to live; I had done this for no particular reason other than the fact that I was tired of working for a living and running the breathless American treadmill. The steady rent money from the apartment I'd recently inherited in Venice Beach, deposited monthly in a bank in Dubai, offered me a comfortable life in Tehran and allowed time to practice my slide guitar and go through the songbooks of my favorite country and western singers. In fact, the point of contact between me and K in Tehran was our unlikely love of American country music. We'd spent many a day at his place and mine arguing the songwriting prowess of Americans with mostly triangular names — men with names like Jerry Jeff Walker, Townes Van Zandt, Billy Joe Shaver, Robert Earle Keen, and Ray Wylie Hubbard.

Now backtrack a year earlier: the last time I'd seen K at an acquaintance's house in Tehran, he'd said to me, "Country music is the only music with honest storytelling in it."

I knew it was a line he must have picked up from elsewhere. Now he pretended it was his, and I let him have it. I only answered, "Honesty? Coming from you, that's saying a lot."

K hadn't batted an eye to what I said that night in Tehran. He was actually too depressed for that. It had been some months now since the government had banned all foreign journalists from entering the country. Which meant K had lost his main source of income.

"Am I supposed to be insulted at what you say?" he asked with little emotion. He glanced around the room, but his eyes settled on no one. "Where is she? Where is your heiress?"

"Not here."

"I've heard about your kind, Nader. You keep the luxury goods hidden from your friends."

"And from my enemies."

"We are not enemies."

"Didn't say we were."

K shook his head. "Tell me, how did you manage to catch her? And do you have one for me? I, too, need an heiress in my life, Nader. And I need her to get me out of this town."

"I'll work on it."

"You do that. Because I happen to know our lovely city is crawling with heiresses these days. Their rich papas keep multiple citizenships and homes in Paris and Rome and the South of France and send their girls to the best schools on the planet to learn six languages and become friends with the children of presidents and kings. And then they come here to steal my living."

I gave K a look. I wasn't sure if he had felt obliged to insult me in return. The heiress he talked about had indeed been my girlfriend of exactly five weeks and two days. A wealthy, wide-eyed Iranian in her early thirties who did in fact have a place in Paris and spoke both English and Persian with a French accent. What's more, she also had places in New York and Los Angeles. And she had come to Tehran for the first time in her life to take in the sights and maybe write an article about her country. Maybe a book, or two books. A friend of hers I knew from my California days had given her my number as a contact, and that was it. She'd decided I was good enough while she was in-country, and that was fine by me. I had nothing else going at the time. Besides, my tenant back in Venice Beach hadn't deposited anything to my Dubai account for over two months now, and I couldn't even scrape the money together to fly out there to Los Angeles and take care of things. In the meantime, the heiress had given a vague hint that she might fly me back to the States with her in half a year. That, too, was quite okay with me. My dignity was at an ebb those days, and being a kept house-guy for a while was an option I didn't mind not refusing.

"Listen," I'd said to Karim, "I doubt that my girlfriend has a need to steal your living."

"You're right, she doesn't. But she steals it anyway. Ever since the government clamped down on the foreigners, that's exactly what's happened. I am out of a translator's job while your girlfriend runs around town with you snapping pictures for her and writing sketches of the genuine Middle East."

"Money helps, K," I said, with a sincerity in my voice that surprised me. "It's the same everywhere. The same cast of characters. It's just that the locations change. This could be Africa. This could be South America. It could be Vietnam or Laos or the Sudan . . ."

"You already mentioned Africa."

"So I did. Her type gets around, is what I mean. They throw parties on different continents. They do fundraisers. They have friends in high places. They have the cultural attachés of a dozen countries in their back pockets. They are the beautiful people, K. And you and I, we're nothing. What more can I say about it?"

"Say nothing, my brother. Just find one exactly like her for me."

Even if I had, I wouldn't have introduced her to K. The man was on the prowl. He was looking for a new source of income, and I was just looking to get back to Venice Beach. The heiress was using me while she was in Tehran, and I was letting her because it cost me nothing. A couple of times she had taken me to gatherings of her rich relatives in Tehran, and I had skulked about by myself drinking obscenely expensive, single-malt Scotch until I was blue. Call me what you like, but this was no one-way street. The heiress may have known six languages, but she couldn't read Persian very well. She needed me for whatever project she had in mind. I'd given her a sob story about not being able to return to LA, and she'd said she'd help me.

But there was another thing. There had been a demonstration some weeks earlier near the Technical University. Usually I'd give any type of a demonstration a wide berth. But this time I'd had no idea there was going to be one. I'd gotten caught in the middle of several hundred engineering students yelling that their vote should count for something. Minutes later the riot police were surrounding us. I would have liked to tell the students to shut up and go home. But it was too late. The three days in jail were bad enough. What was worse was the periodic text messages I'd receive from my jailers afterward: Nader, we know where you are and what you're doing. Next Saturday's demonstration if we find you anywhere except in your own house, it's five years solitary. Or this one: Nader, how are you? Did you know we are in the business of making roosters hatch? And if we can make a rooster hatch an egg, we can do anything.

I was unnerved, to say the least. I was waiting for them to send a text saying that they knew I had an heiress I was ushering around town. I was a rooster and they were going to make me hatch an egg. I wished my heiress would take me to America today instead of six months from now.

A lot can happen in six months. I didn't see any more of K during that time. And my heiress did eventually send me to America. But by the time she did, I had become housebound. I became so fearful of the text messages from THEM that I stopped going out altogether. My biggest fear was that even if I did get a plane ticket, they'd stop me at the airport. They'd send me a text message right there and then saying, Got ya! I could have just turned my mobile phone off. But then they were bound to call my apartment. I'd have to hear a live voice then — Hello, Nader. Turn your mobile back on. We can make a rooster hatch an egg, you know!

Fortunately my heiress had left a month prior to my falling off the edge of the world and becoming housebound. She was back in Paris where her sixty-seven-year-old mother needed her input for a birthday bash she was throwing for her husband's ninetieth. Meanwhile, our situations — K's and mine — had completely reversed. The deeper I fell into my funk, the better K seemed to be doing. When I wasn't busy getting text messages from my special friends, people would call to ask if I'd heard the latest on Heavy K. No, I hadn't heard the latest on Heavy K. I didn't want to hear about Heavy K. I had problems of my own. But of course people told me about Heavy K, anyway. It turned out that he had changed occupations completely and become a video artist. I wasn't quite sure what to make of that, so I just listened, all the while waiting for the ping on my mobile to go off and write me something about roosters hatching eggs. It appeared that K had turned to growing a thick moustache and putting on a black veil that covered everything but his face. He had shot dozens of five-minute videos of himself in various parts of Tehran under the title The Veil Knows No Gender. One of these videos — of him sitting across a long interrogation table, staring at a man who was obviously supposed to be his interrogator — had won some kind of award at a Dubai art festival, the very same Dubai where the bank had recently informed me I was in danger of losing my account with them for lack of funds. K had even received praise in one of those fancy American art magazines where they'd mentioned his name in an article called "The Best Experimental Art of Today from the World of Islam."

I was outraged. K an artist? Since when? And why did my special friends not send him text messages? What did they think the interrogation video was an allusion to? Suddenly K had become the toast of the freedom movement. He was the man who had dared to put a veil on men in order to draw attention to the condition of veiled women. He was the "IT Guy of the Gulf" at the moment. And as if that were not enough, one of the journalists he had interpreted for previously had happened to be in Dubai, seen K and his prize-winning video, and promptly gotten him an art residency — American visa and all included — in upstate New York.

So here I was, rotting away in Tehran while K was going to New York. This is what can happen in six months. Actually more like nine months. But it's the same thing. I wrote my heiress. "Are we going to America, my dear?"

Surprisingly, the answer was yes. And she was even good enough to have her personal travel agent in Paris email me my ticket to be printed and taken to Imam Khomeini Airport.

And that was the last contact I had with my heiress. I had expected abandonment. I knew I was nowhere near her league. But I'd figured if she was willing to send me a plane ticket she'd at least have the courtesy to put up with me for a little bit longer. It seemed like the civil thing to do. But it wasn't to be. I got to Los Angeles. I got myself a temporary job cleaning rooms in a motel right there in Venice while I waited to sell my apartment at a loss with the tenant still in it. And I complained to our mutual friend that the heiress had thrown me to the dogs and wouldn't even return my emails or phone calls. The mutual friend sympathized but told me:

"You need to get your act together, Nader. You need a real job."

"Like what?"

She told me they'd already started interviewing for a new TV/radio channel that was going to be beamed directly into Iran. "Their main office will be in New York, and the whole thing has the backing of the opposition movement and is being bankrolled by the Americans."

I had never felt failure as acutely as at that moment when the mutual friend told me this. I looked at her with a long face that I couldn't shed. We'd been casual friends when we'd both started at Santa Monica College. She'd been a rich Iranian punk girl for a while, until she married an Iranian lawyer in Beverly Hills and gave him two kids. I realized now that I knew nothing about her life. I'd never even seen her kids. I didn't know much beyond the fact that we'd smoked grass together sixteen years ago, kept in touch erratically, and today she'd driven out here to Venice, outside of this motel I was slaving away at, and she was giving me advice that I probably sorely needed.

"Why the sad look, Nader?"

"You know the story. Every failed fellow who couldn't make it abroad ends up working for some broadcast station bankrolled by the Americans or the British. All I need now is to join another Voice of America, darling."

The mutual friend looked at me. We were sitting on a decrepit bench by the motel, and her light blue BMW was parked next to us. I had a vision then of Heavy K's prize-winning video of him and his so-called interrogator across the long table and wondered how that son of a bitch was doing.

"Did you say failed?"

"Yes, yes. I know. That would be me, wouldn't it?"

"So what are you waiting for? Most of those guys interviewing for the job haven't even seen a grain of sand of the Middle East for thirty years. You've been living there. You know the place inside out. You're a shoo-in. I'll have my husband put in a good word for you. He knows a few people in Washington."

"How are your kids?"

"Shut up! You don't give a shit about my kids. They're fine. And . . . forget about that other thing."

I did forget about it. I didn't give another thought to the heiress. I cleaned toilets and made beds at the motel until my apartment was sold, and then I took a one-way flight to New York. I did my interview and did well enough to be told to show up in DC three days later for a second interview and some vetting.

It was between that first interview in New York and the second one in DC that I ran into Heavy K at that party of media people in Manhattan. I'd come here hoping for some contact. Maybe I'd even find myself a new heiress, or I would run into my old one. Or, at the very least, a couple of people might direct me to another job in case the television gig I'd interviewed for didn't pan out. There were to have been a lot of journalists here, after all. So I'd invited myself without an invitation. But one look at the guests, and I knew the night was a misfire, again. Except for a middle-aged man who, I heard whispered, had wheedled a last interview with a famed terrorist before the latter's disappearance, the rest of the invitees looked fresh out of school. A group of these youngsters hovered near the last-man-to-interview-the-famous-terrorist, hoping to get in a word. As for the last-man, he just sat there with an impassive face, refusing to take off his black trenchcoat while looking vaguely ominous, as if he'd produce the reincarnation of the disappeared terrorist any minute out of that trenchcoat.

Then when I was on the verge of calling it a night, who else should I see coming out of the elevator but Heavy K? I was both glad to see him and a bit embarrassed. Glad because I had someone to talk to, embarrassed because I imagined him on the make and on his way up as a great artist while I was simply spinning my wheels, looking for work, and I no longer even had an heiress to fall back on.

Cut then to said night in Manhattan and K saying, "Can I ask you something?"

"If it's about my heiress, no. I am finished with her."

"Oh, I know that already. It's not about that. Wait here."

I watched as K joined the bar, looked for the most expensive drinks, and poured himself not one but two beer-sized glasses of two separate hard drinks and brought them back to our corner. His hunger for those drinks reminded me of my own time in Tehran when I had gone to the homes of my heiress's billionaire relatives. And something about this made me think that K was not doing nearly as well as I'd believed.

Downing the first shot quickly, he asked, "My question is this: Nader, what in god's name are you doing here?"

What could I say? I told him the truth. I told him about my situation with the heiress, told him about what I'd been doing in Los Angeles, and told him about coming out here to interview for the job with the new TV/radio station. I even told him about the crazy text messages I'd been receiving in Tehran during my last days there.

"You poor bastard. Join the club."

"Which club?"

"I was interviewing for a job with those guys, too, today. I overheard the same thing you overheard about tonight. That there would be a party at suchand- such address. Journalists. Middle East hands. Etcetera, etcetera. Except look around you. No real journalists, no Middle East hands. A bunch of outof- work journalism school graduates looking for the same thing as you and me. We're pathetic." K shrugged. Then grinning, he added, "Well, at least the place is nice and big and warm and there's free drinks. Lots of free drinks."

"Did they ask you to show up in DC for a second interview?"

K nodded.

"But why are you interviewing for work anyway? I heard you were a rising star."

"I was, until I wasn't. It's hard here, brother. I got some residency upstate, which is going to run out in a few weeks. I was spending too much money when I thought I could just keep making videos of my veiled beautiful self and these crazy bastards would keep writing about my art. But then one day I woke up and saw that everybody and their mother was putting on a veil and photographing themselves and making videos. I'm no longer unique. I don't even have a gallery in this town. No one takes me seriously. No one returns my calls. Not even the woman who brought me here."

I took the extra drink from his hand and downed it myself. "That is called poetic justice, brother K. You had a nice charade going on for a while. They thought you were the voice of the opposition in Tehran. A genuine freedom fighter. An artist. Now look at you. Look at us!"

"Brother Nader, take me out of this place. Is there somewhere we can go hear some country music?"

I took him to a place on Third Avenue. It was a Friday night. The country acts were not all that good, and the place was packed with an irritating college crowd. It was depressing. Plus I'd already begun running through my money from the sale of the Venice Beach place. All in all, it was a bad situation for me. If the TV job came through I'd be set again. In the meantime, I had a studio way out there in Flushing. I hoped K wouldn't ask me if he could move in. I'd have to say no.

We watched the whole tedious show. The last band that came on had snap, though. They played a combination of western swing, rockabilly, and at times just plain old-style country. They had rhythm, and the lead female voice had real presence and a big beautiful pair of blue eyes that, I could tell, were mesmerizing K.

We drank more than we could handle that night. I got sappy and homesick. I imagined I even missed those text message from my special friends. They showed that at least somebody cared about me. They kept track of where I went and who I saw. Even those three days in jail, where I'd spent hours upon hours standing with a blindfold and with my nose to the wall until every cell in my thighs and lower back felt like it was on fire, I'd felt more alive than I did now. In fact, if anything I felt most alive then, because there's nothing like physical pain to remind you that you're not quite dead yet.

I told these things to K, and K did not even listen. He seemed to be on another planet altogether, watching that band from Texas. He stumbled up to them after the set and talked with each member of the band while I poured my sorrows into my drinks. Afterward, I don't remember a thing. I have no idea how I got home and what became of K. I spent the next day with a gargantuan hangover, and two days after that I was in DC for my second interview. Again, I did well enough, and they told me I'd be hearing from them soon. I looked for K, but he didn't seem to have come to DC. At least not that day. I went back to New York and waited. Days turned into weeks and months. Nothing. No job. Not even a hint of a job. Later I found out that at the last moment the Congress of the United States of America had decided not to approve fresh funds for another opposition TV station in the Middle East.

My money was dwindling, and my overdrinking wasn't helping matters much. Sometimes I would have these brainstorms, which would quickly pass — like the day I went and bought a headdress from one of the Arab shops on Atlantic Avenue and brought it home to cover my head with. I looked in the mirror and saw that I looked ridiculous. Still, I should get a camera and take a few pictures of myself like Heavy K had done and send the pictures to art galleries. I could write to them and mention that I'd been in jail in Tehran. That would bring some cachet to my art. They'd take me seriously. I was the real freedom fighter, not Heavy K. The hell with him. Where was he?

I ended up using the black headdress to clean the beer on the kitchen floor that I'd been spilling over a period of two months. I watched a lot of TV. I imagined myself in front of the camera at that TV station that was to have been bankrolled by the sweat of the American taxpayers. I could have been somebody if that job had come through. Now what? I could try to get in touch with my heiress. She had a place right there in Central Park West.

After a while all I watched were country music stations and old cowboy films. One night around three in the morning I was watching a special program about the country music scene in some American town or other. I'm inclined to think it was Austin, Texas, though my brain was mushy and I can't be sure of it. What I do know, though, is what I saw, or rather who I saw that night on my television set. It was Heavy K. Fixer Karim. Iranian translator turned video artist turned . . .

There he was, fronting some country band right in front of my eyes at three in the morning. The program was for connoisseurs, showcasing mostly unknown talent. K's hair had grown long. He is not a very big guy. And with his vest, the black boots, the red and blue scarf draped across his neck, plus the cowboy hat and the thick moustache he'd kept since his video artist days, what he looked like to me was a Mexican cowboy in semidrag. I sat there in a daze while K Hey & the Camelbacks went through a short set that included many questionable lyrics the two of us had pasted together on those lazy Tehran afternoons when there was nothing else to do — lyrics like, I was just a drifter / until my heart went crack / I turned to drinking teardrops / but I still can't get it back.

It was K, all right. K Hey with the slightly crooked nose. Him with the acoustic guitar and the few chords he knew, letting the three other band members carry him while he sang into the mike with his Australian-tinged accent about cheated lives and drinkers on the run. He'd given up the Islamic veil for the cowboy hat, but there was no question in my muddled head it was him. I lay sprawled on the cat-piss sofa in my furnished rental in Flushing, Queens, and watched K go through several original songs, finishing with a rendition of Hayes Carll's beautiful solo "Arkansas Blues." The backdrop was now dimmed while K played the simple bars by himself and sang in the most heartbreaking Australian-tinged accent in the world:

Look out, I believe I'm Texas bound . . . I been all around this land to pay my dues . . . And I just can't run from the Arkansas Blues.

I went to the fridge and took out my last Pabst Blue Ribbon beer and popped it open. I was crying. He had done it. K had done it again. That son of a bitch! He'd reinvented himself.

"Shit!" I muttered in what I imagined was a Scottish accent — "shyt" to rhyme with "kite." And therein I also imagined I had found my own rhythm: if K could sing country with a fake Australian accent, then I could do the same with a fake Scottish one — Nader and the Nitro Riders.

It didn't happen, of course. If it had happened, it would have been beautiful. Beautiful symmetry. But life is not that way. There are those that can, and those that can't. Just ask my special friends back in Tehran who know how to make a rooster hatch an egg.

Excerpted from Tremors: New Fiction by Iranian American Writers. Copyright © Salar Abdoh. Excerpted by permission of University of Arkansas Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.