Book Excerpt: 'The Taliban Revival' by Hassan Abbas

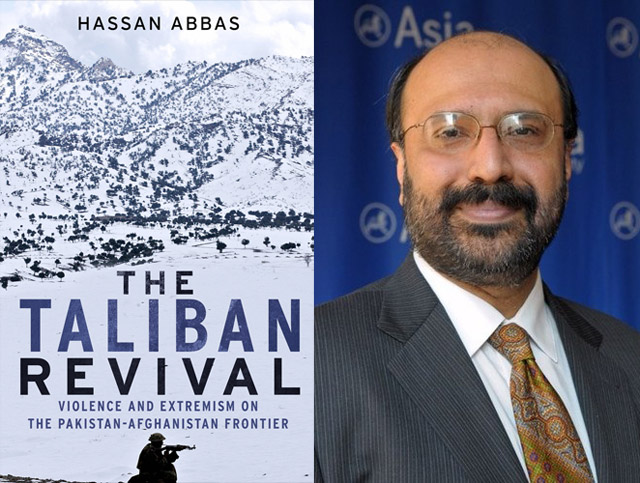

"The Taliban Revival" (Yale University Press, 2014) by Asia Society Senior Advisor Hassan Abbas (R).

On Wednesday, July 9, 2014, the Asia Society Policy Institute welcomes Hassan Abbas to Asia Society's Washington office for a panel discussion on Afghanistan.

On Wednesday, July 9, 2014, the Asia Society Policy Institute welcomes Hassan Abbas to Asia Society's Washington office for a panel discussion on Afghanistan. In 2001, when NATO forces entered Afghanistan in their offensive against Al-Qaeda, they also aimed to eradicate the Taliban, Islamic fundamentalists who had lent help to Osama bin Laden. The Taliban were flushed out of Afghanistan's major cities and a new, interim government under Hamid Karzai was established. However, a new book by Dr. Hassan Abbas shows that the Taliban, rather than disappearing, instead persisted and regrouped to the point where they were once again a significant security threat.

In The Taliban Revival: Violence and Extremism on the Pakistan-Afghanistan Frontier (Yale University Press, 2014), Abbas chronicles how the Taliban managed to not only survive, but spread as an insurgent movement. Furthermore, he writes, understanding the causes of this seemingly mysterious "Talibanization" is essential for reversing its resurgence in Pakistan's Federally Administered Tribal Areas. Drawing on research and interviews in the area, The Taliban Revival presents a comprehensive account of the Taliban's fall and resurrection, beginning with Pakistan's volatile Pashtun frontier, weaving through the U.S. war in Afghanistan, and leading up to current U.S. counterterrorism efforts in Pakistan.

Hassan Abbas is Professor and Chair of the Department of Regional and Analytical Studies at National Defense University's College of International Security Affairs in Washington, D.C. He is also a Senior Advisor at the Asia Society and was an Asia Society Bernard Schwartz Fellow in 2010. Below is an excerpt from his book.

In theory, a negotiated settlement with the insurgents is a necessary prerequisite for an end to the ongoing conflict in Afghanistan. But the million-dollar question is: at what cost? Reconciliation with the Taliban is an issue that affects more than just Afghanistan. It has regional implications: the interests of all neighbouring countries need to be taken into account before any major political adjustments can be made. The reality is that the Obama administration was initially very reluctant to pursue a negotiated settlement with the Afghan Taliban, though President Karzai had already reached out to them for "reconciliation." After 2008, Pakistani intelligence also made a case to its U.S. pursuing talks with the Afghan Taliban, and it even offered to mediate. On the ground in Afghanistan, there was an important initiative from German diplomats to talk to the Taliban in 2010.

The problem is that the Afghan Taliban are no longer a hierarchical organization, with leaders who are easily identifiable. A range of localized insurgent groups with different agendas and grievances are operating in the field, as are criminal networks and organizations that are semi-independent Taliban affiliates, such as the Haqqani group, which uses Pakistan’s tribal areas as a base from which to conduct and coordinate its activities in Afghanistan. American defense officials believe that 10-15 percent of insurgent attacks inside Afghanistan are directly attributable to Haqqani group warriors. Pakistan is capable of bringing the Haqqani group to the table — and presumably others from the inner circle of Mullah Omar — but it is doubtful whether the Taliban sitting in Pakistan could negotiate on behalf of all Taliban insurgent leaders operating inside Afghanistan.

No major communication breakthrough with the Taliban leaders was in sight when former U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton delivered a major policy speech at the Asia Society in New York in February 2011, in which she set out three conditions for the Taliban if they wanted to come to the negotiating table — sever relations with Al-Qaeda, renounce violence and accept the Afghan constitution. For the Taliban, this was a non-starter. But they had little inkling that Secretary of State Clinton was moving in this direction after having overcome stiff resistance from the other important power centers in Washington. For Pakistan, it was a welcome development, though Islamabad believed in a slightly different approach, suggesting to the U.S. that the three preconditions could be converted into the end goals of a negotiated deal. Washington agreed in principle, and Pakistan was given the go-ahead to play its part in making this happen.

At the time, Pakistan was itself under tremendous pressure from the TTP — the local faction of the Taliban — which was constantly on the offensive, targeting major military and intelligence infrastructure counterparts from inside Pakistan. For Pakistan, an accommodation between the Taliban and Kabul would ease the pressure and also reinstate Pakistani influence in Afghanistan to balance the inroads India had made there.

Karzai, who was running his parallel reconciliation efforts via the "High Peace Council," led by former President Burhanuddin Rabbani, wanted to control the process, but Pakistan was not inclined to trust him, and opted rather to communicate direct with the U.S. in this regard. The Afghan approach — enshrined in a document entitled "The Peace Process Roadmap to 2015" — emphasized an "Afghan-led" and "Afghan-owned" process that would ensure the freedoms and liberties of all Afghans. The assassination of Rabbani at the hands of Taliban (whose spokesman claimed responsibility) in September 2011 was to be a blow to the Afghan reconciliation effort.

Meanwhile the bold U.S. operation in the Pakistani city of Abbottabad in May 2011 to eliminate Osama bin Laden, followed in November 2011 by the death of 24 Pakistani soldiers and officers at the hands of NATO forces at Salala, a checkpoint on the Pakistan–Afghanistan border, changed the atmosphere in Pakistan and led to a deterioration in U.S.-Pakistani relations that froze the planned negotiation initiative.

The situation only improved in mid-2012 after some "give and take" that led to a resumption of Pakistani efforts to bring the Taliban to the negotiating table. Over two dozen Taliban militants languishing in Pakistani intelligence "guest houses" (or in some cases in the "protective custody" of local militant groups) were advised to return to Afghanistan. In official U.S.-Pakistan discussions on the subject, Pakistani military and intelligence officials continued to emphasize that there were no "guarantees" and that they only promised "facilitation."

The opening of a Taliban office in Doha, Qatar, in June 2013 for talks with the U.S. and the Afghan government was an important step. The initial agenda included the issue of Taliban prisoners at Guantanamo Bay and the removal of some Taliban leaders from the UN sanction lists.

The plan foundered, however, when the Taliban erected a plaque outside the office that read "Political Office of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan" and hoisted the Taliban flag — despite a categorical objection from the U.S. According to an American insider, it was all a misjudgement on the part of the government of Qatar, which acceded to the Taliban request. Anyway, President Hamid Karzai was not amused. He conveyed his displeasure to Qatar, and that led to cancellation of the whole process.

The whole episode exposes a debilitating disconnect, caused by mutual apprehensions on the part of all the sides involved in this sensitive and controversial enterprise. Soon afterward, a senior Pakistani diplomat asked me: "Are the Americans really serious in negotiating with the Taliban, or is this only a tactic to force Pakistan to show its hand?" The inference was that perhaps the U.S. is indirectly attempting to drive a wedge between Pakistan and Afghan Taliban leaders. This perception explains Pakistani skepticism about U.S. interests and its long-term commitment to the region.

The critics of reconciliation argue that the hard-core Taliban would never agree to a democratic order in Afghanistan, as they abhor the concept of citizens’ rights and political freedom. Ethnic and sectarian minorities in the country are especially concerned about the reversal of the progress made by Afghanistan in these areas since 2001. A major terrorist attack in Kabul, which targeted a religious procession of Shia Muslims in December 2011 and killed 55 people, showed an increasing convergence between sectarian terrorists in Pakistan and Afghanistan.

The Pakistani Taliban have been especially fond of such attacks, but the track record of the Afghan Taliban is equally tainted (think of the atrocities perpetrated on the Hazara community in Afghanistan during its time in office). The Shia Hazara living in Quetta, the capital of Pakistan’s Balochistan Province, and Shia professionals across the country have faced a debilitating reign of terror in recent years. There has also been an unprecedented targeting of Sufi shrines in Pakistan.

It is intriguing why the Taliban and their affiliates should specifically target those who commemorate Hussain ibne Ali, the hero of the battle of Karbala in the year 680. This grandson of Prophet Mohammad faced the military might of the Muslim Empire (ruled then by a despot, Yazid ibn Mu’awiya) with only about 70 supporters, including many children. Hussain had refused to abide by Yazid’s tyrannical reign and had challenged the way he distorted Islamic principles in his hunger for power and territorial expansion in the name of Islam. Hussain was martyred in the most brutal fashion, along with many members of his family. For fourteen centuries both Shia and Sunni Muslims have revered his legacy; but a major chunk of the Taliban thinks differently.

Any political settlement in Afghanistan that does not provide guarantees to minority sects and ethnic groups is highly unlikely to resolve the looming crisis. Despite its flaws, the present Afghan constitution provides a balance whose essence is worth protecting. Some reconcilable elements of the Afghan insurgency are certainly aware of this reality, and many of them are prepared to work within the new system (with some adjustments); but Mullah Omar’s take on the issue is different.

In a public message in August 2013, delivered on the occasion of the traditional Muslim Eid holiday, he took ownership of the Doha negotiation effort, proving that he was in close touch with Islamabad.

But his statements sounded contradictory at best. Uncharacteristically, he asserted "we [the Islamic Emirate] believe in reaching understanding with the Afghans regarding an Afghan-inclusive government"; but in the same breath he called the democratic process a "deceiving drama" and distanced himself from the Afghan elections scheduled for 2014.

Mullah Omar would like us to believe that he is moving towards the middle ground; but this choreographed message could well be a deception. He dreams of being crowned in Kabul once he sees the last American soldier departing from Afghanistan. And he holds out the prospect then of granting people rights as he deems fit, according to his perverted interpretation of Islam. But that is simply not going to happen. Though very shaky and lacking confidence in its future, Afghanistan has moved on and is unlikely meekly to accept a 1990s-style Taliban takeover.

Islamabad’s attempts to negotiate with the Taliban remain fruitless, but the Sharif government is intransigently committed to keeping all the options open. General Raheel Sharif, the unassuming new army chief, however, convinced his political masters that a tit-for-tat response to terror attacks is a more sensible approach. The general can transform thinking in his own institution, too, but it is going to be a truly daunting task. Pakistan needs a strong and cohesive army that honestly adheres to democratic norms.

There are many lessons to be learned from this seemingly unending saga by the U.S. and its allies. Firstly, it never hurts to study the history and culture of a people you are attempting to engage and reform; ideally, it should precede any interaction. Secondly, civilian capacity-building is as critical as securing an area, and must be handled by trained and qualified professionals. The selection of local political partners is crucial to the building or destroying of the credibility of a project in the public eye. Lastly, as unwieldy as it may turn out to be, regional problems require regional solutions.

Excerpted from The Taliban Revival: Violence and Extremism on the Pakistan-Afghanistan Frontier by Hassan Abbas. Copyright © 2014 by Hassan Abbas. Excerpted with permission of Yale University Press.