In 2013, Literature Festival Provides 'Healing Touch' for Troubled Karachi

KARACHI — It sounded like a bomb blast. The violent rumble rent the air, drowning out the moderator's words. Gasps and startled voices filled the auditorium, finally giving way to murmurs. Torsos bent away from the windows straightened up again as everyone realized that there was no smoke or rubble, no violent jolt or smell of burnt flesh. "It's raining," said a woman in the middle row, relief mixed with weak laughter in her voice, addressing no one in particular. The view outside through the glass had gone from a cloudy landscape to sheets of slate grey that opened up like a massive showerhead over the dusty city.

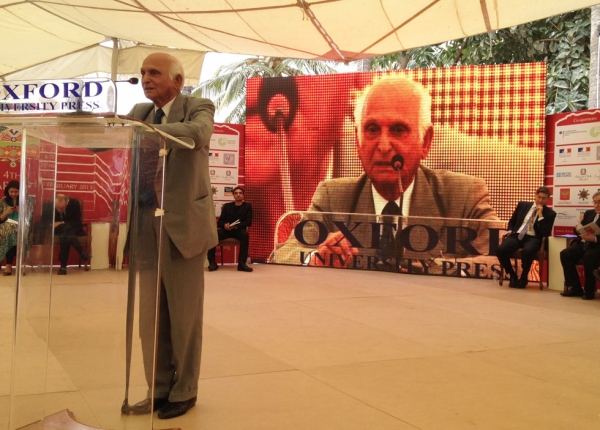

A literature festival becomes a political statement in a city like Karachi, where bomb blasts, like thunderstorms, have become part of the natural order. In a town rife with ethnic violence, turf wars, targeted killings and militant attacks, the celebration of books here last week felt fragile yet significant. "In less than four years the festival has become a credible, very attractive event at a time when Karachi has been going through its worst period," said former Information Minister and author Javed Jabbar. "This contrast is the most remarkable aspect of the festival at a time when everything is supposed to be destructive about the city."

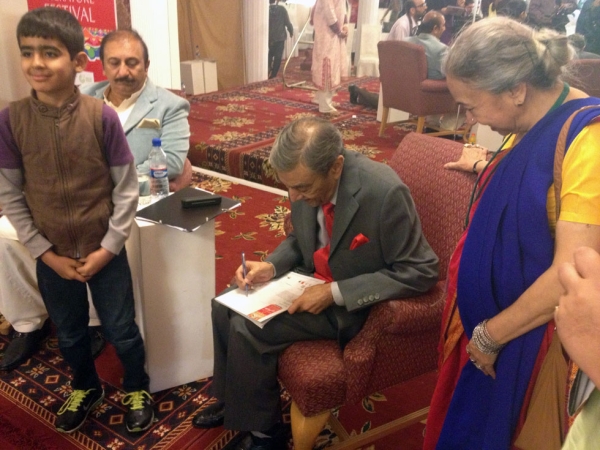

The Karachi Literature Festival (KLF), held this year from February 15 through 17 at the Beach Luxury Hotel, has grown rapidly since its inception in 2010. Inspired by the Jaipur Literature Festival across the border in India, the annual event was the brainchild of Ameena Saiyid, managing director of Oxford University Press (OUP) in Pakistan, and writer and translator Asif Farrukhi. In four years, the festival has expanded from 34 sessions and 37 speakers in its first year to 129 sessions and 214 speakers this year. Attendance has risen from 5,000 to around 30,000 in 2013, and a parallel Children's Literature Festival was also held in Karachi this year.

The KLF has consistently managed to attract well-known writers from around the world, with Shamsur Rehman Farooqi, Karen Armstrong and William Dalrymple having been keynote speakers. Homegrown talents like Mohammed Hanif, Mohsin Hamid and H.M. Naqvi represent the vibrant new voices of Pakistan, and are one of the reasons why the festival has created such a draw for the public (despite, this year, a number of key Indian speakers' being absent, like writer Shobhaa De and poet and lyricist Gulzar).

"I feel the event is a balm and it's like a healing touch for all of us in Karachi who are so disturbed and so wounded by what is going on," said Festival co-founder Saiyid. "It is only through expressing our thoughts and our feelings about what is going on that we will find some peace."

With violence on the streets outside, security remains a major concern for the organizers. According to Saiyid, the government has provided adequate security for the event. The Karachi police, she said, have been "extremely helpful."

A number of officers could be seen patrolling around the periphery of the venue. At the main gate of the Beach Luxury Hotel, a guard with a handheld metal detector checked bags before allowing visitors to walk around the heavy barricade and cross the massive parking lot to the hotel entrance, where their bags were subject to a manual inspection by two more guards before they were allowed to walk through a scanner into the lobby. One of the guards flipped through the pages of a slim hardcover in my purse. Apparently even the literature itself was suspect.

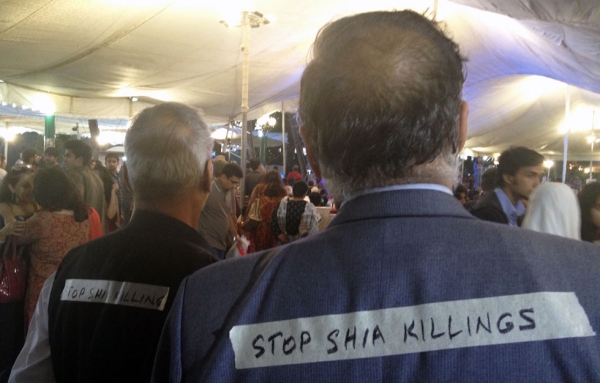

The law and order situation in Karachi has slowly deteriorated over the last few years, with almost 800 reported killed in 2012 alone by Human Rights Watch. With elections expected sometime in March this year, an already tense city seemed to teeter at the edge of a violent precipice. By the last day of the festival, news of the Hazara Shia killings — over 80 people reported dead from a bomb planted in a busy market in Quetta — was everywhere.

Black armbands and moments of silences marked the closing day of the festival as people expressed their grief. Speaking to the Sunday panel on "Pakistan Through Foreign Eyes," Yassin Musharbash, a journalist with German news magazine Der Spiegel, could hardly believe we were all still there at the event.

"This is a country where people are gathering here and talking about Balochistan in all openness and two hours later you have 80 dead in Quetta. A terror attack on a scale where most other countries would stop operating for three weeks out of shock," he said. "I don't know many other countries where that sort of thing happens."

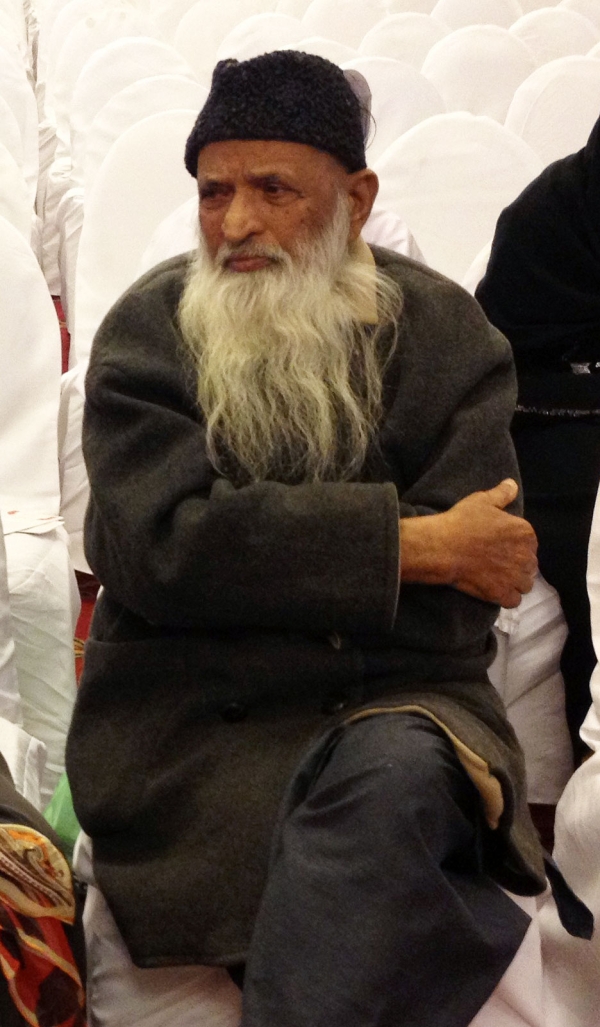

Still, the festival went on — just at it had in previous years, because that is what Karachi does. Yes, the violence continues, but so does the struggle to change the country. Abdul Sattar Edhi's humanitarian work in Pakistan was commemorated with the launch of a book Half of Two Paisas: The Extraordinary Mission of Abdul Sattar Edhi and Bilquis Edhi, about his life and decades of work. Novelist Mohammed Hanif unveiled his small book on a very big problem — a hard-hitting 46-page profile of missing Balochis who have been "disappeared" by shadowy paramilitary forces. Meanwhile, prominent Urdu poetess Tanveer Anjum read an ode to Pragaash, a Kashmiri all-female rock band that had to disband after security threats as a result of being deemed "un-Islamic."

But it was Malala Yousufzai, whose voice was not heard at the festival, who most fully embodies the struggle of literacy and education against the forces of terror and ignorance in Pakistan. Malala had been asked to serve as the official ambassador for the Children's Literature Festival, but was undergoing further surgery in the UK at the time. Still, her inspiration was felt. Issues of education and human rights were central to the discussion. And the voices of women in particular increasingly took center stage.

Sitting beside me during one of the panels was a pretty, bright-eyed 20-year-old, Shehzeen, who had recently started working for Edhi to help support her family after her father fell ill. "I really like the atmosphere at the festival," she told me. "I want to educate myself more after meeting everyone here. I want to build a life before I get married." Her friend, Pramilla, also working for Edhi, felt much the same way. "My parents are very supportive, but my uncle is Tableeghi [a conservative Islamic party], he does not let the issue go. A girl must get married off. I want to study and not marry."

The day after the festival, protests wracked the city. The main artery to the airport, Sharah-e-Faisal, had been shut by security forces. I wondered if those who had come in from elsewhere had made their flights the night before, or whether their stays would be involuntarily extended. The street outside my apartment was quiet. Offices were shut, the usual buzz of midday traffic was just a distant murmur. There was nowhere to be. Nice and quiet, I thought, the perfect chance to sit down with one of the new books I'd picked up at the festival.

Asif Aslam Farrukhi said it best during his opening ceremony speech. "This city has been described as a nexus of international terrorism, and how we all wish that it becomes known for the festivity associated with literature more than anything else."

Nadia Rasul contributed to this post.