Azar Nafisi: Literature as Celebration and Refuge

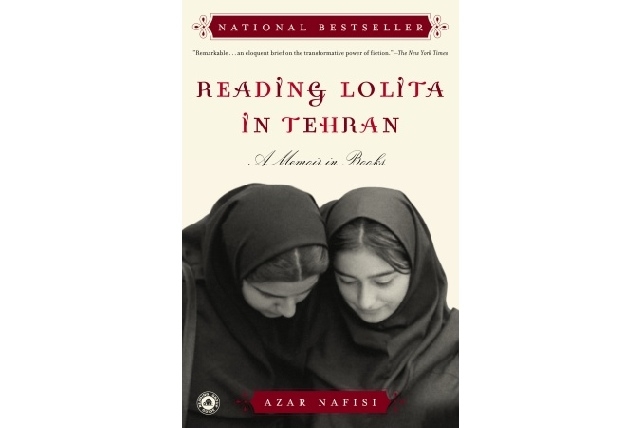

Azar Nafisi is the author of Reading Lolita in Tehran: A Memoir in Books, and a Visiting Fellow and professorial lecturer at the Foreign Policy Institute of the Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) in Washington, DC.

A professor of aesthetics, culture and literature, Dr. Nafisi held a fellowship at Oxford University teaching and conducting a series of lectures on culture and the important role of Western literature and culture in Iran after the revolution in 1979. She taught at the University of Tehran, the Free Islamic University, and Allameh Tabatabaii before coming to the United States—- earning national respect and international recognition for advocating on behalf of Iran’s intellectuals, youth, and especially young women.

Dr. Nafisi spoke to Asia Society while she was in New York for a panel on contemporary Persian culture at the Asia Society.

You say in your book, Reading Lolita in Tehran, that you returned to Iran in 1979 after 17 years abroad. Can you tell us a little about where you were educated and where you grew up?

I grew up in Iran till I was 13. I was sent for the rest of my education first to England, then for a very short time to Switzerland, and I spent my university years in the United States. Even during my time away, I would come back to Iran for vacations, including on one occasion for a whole year (when my father was jailed). I only returned for a long period of time in 1979, though.

Can you explain why you chose to write your book as a mixture of genres: autobiography, fiction and literary criticism?

This idea came to me when I was writing my book on Nabokov in Persian [Anti-Terra: A Critical Study of Vladimir Nabokov's Novels]. I always had this preoccupation with the way reality and fiction mingle, the way that reality is transformed through fiction and vice versa. As I was working on the book, I kept thinking how wonderful it would be to write about all the different times, all the different stages in my life, when I was reading Nabokov. In the last chapter of Anti-Terra, I did a little bit of that. But in Iran I could not tell the truth about my life; not only in a political sense, but in a personal one. I wanted to explain, for example, how I first read Nabokov, but in order to do that I would have had to reveal that the person who gave me my first Nabokov was a man with whom I was very much in love. I did actually mention that in my Persian book, but my friends told me to cut it out! When I came to the States, I simply wrote the book that I had had in mind, but could not write, in Iran.

Ultimately, though, even if you have a clear idea of what you want to write before you start, once you begin work, the form takes you over in a sense; you discover things that you did not know, and the book begins to take on a life of its own.

How do you see literature as having redemptive possibilities? This is a theme that surfaces throughout your book.

Literature in and of itself should be read for the pure sensual pleasure of reading, which is quite unique. Reading sharpens your imagination, it creates an empathy with people and places that you may never yourself experience. This is the compassionate side of literature: by placing readers in contexts with which they are not familiar, it opens them up to different possibilities; readers begin to empathize with characters and places very far from their own experiences.

Books become even more important in repressive regimes. Under totalitarian conditions (as existed in Iran when I was living there), the emphasis was on confiscating individual freedoms, and books have the capacity to redeem some of that lost integrity and sense of individuality. You want to go somewhere which tells you that individuals are cherished, that they are celebrated, and literature, no matter where it comes from, does that. It is a celebration of life.

What initially drew you to literature?

I don't even remember anymore because in my family literature was the most important aspect of our lives! I must have been only three or four when my father would put me to bed by telling me stories from classical Iranian literature. My father would also play these games with me: whenever he wanted to tell me something, he would tell it to me in the form of a story. If he was mad at me, he would tell me about this father who had this daughter whom he loved very much but she had done something wrong, and so on. So we would create these stories together. Ever since I can remember, literature has been a refuge as well. I cannot think of a time when I was not reading.

Who do you consider your main literary influences?

I mention in my book that when it comes to works of literature, I am a very promiscuous person! It is a very mixed bag. My father's stories were mainly classical Iranian tales, but he also told me tales from La Fontaine, Hans Christian Andersen, and the fairy tales that exist both in the East and in the West (equivalents, for instance, of Cinderella or Sleeping Beauty exist in Persian as well).

Then when I started reading, I read everything: Persian and European literatures; my first foreign influences were Russian and French authors, and then English. Since then I have become used to thinking of literature as belonging to no one place. That is why I am always surprised when people say that I write about Western fiction because in my mind I am just writing about these books. There are certain things in the world that are portable and that are universal. I think that works of art do not belong to one nationality although they give you a great deal of knowledge about specific places and peoples but you can empathize with them on different levels, and one level is universal.

You mention in your book an incident in Tehran while you were teaching of an Islamist student citing Edward Said. How is it that you felt that this was a misappropriation of Said's work? What is it about Said's work as a literary critic and a political commentator that strikes you?

It is very difficult to comment on Edward Said because there are so many sides to him. He is very seductive because he is an extremely erudite, intelligent and charismatic character. I think his main passion is music and when he talks about music you can tell how much joy and pleasure he gets out of it. A lot of people oppose Said based on political issues but I do not. My problems with him are purely literary.

There are certain arguments he makes in his readings of literary texts that I cannot agree with. After this Islamist student spoke to me, I read Culture and Imperialism, which in large part I disagree with. There is a paradox in Said's own theories because on the one hand he is very much a Western writer. Even his theories criticizing colonialism come from the West. On the other hand, I do not think it is possible to reduce a work of art to just politics. Many of the writers he speaks about could be very reactionary, but I think that the redemptive power of literature is that - when it is good - it can transcend the author's prejudices. This is not something that Said takes into account.

Of course there were periods of history when there were writers who were not just biased, but absolutely racist; Count Gobineau comes to mind, among others. But I do not think you can say that from Aeschylus to Balzac to Flaubert, everyone was an Orientalist.

For me, the relationship with the West is a paradoxical relationship. On the one hand, there is definitely economic and political exploitation, and we see that even today, even as we speak. This I would very much insist on, and I don't think we should whitewash that. On the other hand, I think there is another level of communication, which is cultural, where there is also exchange. It is not just one-sided. Writers like Nabokov or Rushdie came from other parts of the world and enriched English language and culture in a way that no indigenous author could have done. So it is not just that the West gives us knowledge which we imbibe; we are constantly giving and taking. I have certainly been enriched by the cultures of the West and other parts of the East. This is the positive aspect of the relationship between East and West, and it occurs in the realm of culture. I cannot reduce the relationship to one component: I would neither say that because we have this fantastic relationship with the West in terms of culture, other parts should be forgotten (the political exploitation, for instance) nor do I think that we can reduce it to politics and talk about these novelists as all assisting imperialism. They had their own contradictions: when Jane Austen lived in England, there were people who were very much anti-slavery, who were very much anti-colonialism. Theories of anti-colonialism came out of the West. People cannot be essentialized into one component; that is what I object to.

On top of all this, what happens with people like Said is that other people take his theories and simplify them. The theories become very simplistic in the hands of people who are polarized in this way. In a country like Iran, many Islamists took his theories and jubilantly proclaimed what they believed he was saying. But of course Said's theories are not as simple as these people claimed. But that is always the danger with ideas; other people will run off with them and there is nothing you can do.

You have suggested elsewhere - and indeed this permeates much of your book - that Islamists are hurt most by a sense of individual dignity, by individuals who think for themselves. Could you elaborate on this?

When I came back to the US, I discovered that over here unfortunately there is a very simplistic view of what we call "Islam" (as there was in Europe when I lived there). What I was trying to point out is that when we talk about Islamism we are not talking about Muslims to begin with because Muslims are so various. First of all, the Middle East has a very tiny minority of the world's Muslim's population; the majority of the Muslim population lives elsewhere. Secondly, think of the enormous variety in what constitutes the Muslim world: Indonesia, Nigeria, Iran, Turkey, Saudi Arabia; none of these countries or cultures are the same. We do not call France and Germany "Christian" countries; why do we do this only with Islam?

What I wanted to say is that the Islamists have more in common with totalitarian systems in the West than they do with ordinary Muslims in their own societies. In totalitarian societies - whether the Soviet Union or China or Iran or Afghanistan - the first thing that the state is threatened by is individual freedom of thought. The first thing they want to confiscate is your sense of yourself, and your sense of yourself as an individual. So we must respond with our imagination, our thought; we cannot destroy them through violence. We have to confront them on our own grounds.

In the book you say that Islamic feminism is a "contradictory notion." You have also said in an interview recently that "Islam is not that developed" and that the reformists in Iran were inspired by European secular intellectuals because "when they looked to their own past for insight, what they found was a dead end." Do you think there is something intrinsic to Muslim traditions - in all their complexity and variety, as you point out - that makes them incapable of change, or essentially oppressive?

No. If you look at the history of any country, when there is a period of stagnation or ossification, change comes both from within and from without. This is why I believe that works of thought do not belong to any specific geographical location. What I was saying is that in Iran, when the reformers started questioning from within, they also turned without.

The point about Islamic feminism is simply that we do not talk about Christian feminism or Judaic feminism, so why Islamic feminism? There are Muslim women who are fighting for women's rights but what really bothers me - and I think this is an Islamic discourse that Westerners have taken on - is that the West constantly segregates Islam. What are Islamic human rights for instance? Are we a different species? I think it is very insulting.

I have to constantly insist with experts in the West that the West does not have a monopoly on life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. It is insulting to say that Muslim "culture" is different: does this mean that Muslim women like to be flogged, or that they do not mind being stoned, or that Muslim girls like to be married at the age of 9? Why are they doing this to us? If they want to talk about our culture, I say let them talk about Ibn-'Arabi, and Rumi, and Hafez. Let them remember that the word "algebra" came from Arabia. Do they like to be reminded that burning witches in Salem was part of the culture of Massachusetts? Well, it was but they now take pride in having changed it.

Right now, Islam is in crisis. It needs to review itself, it needs to change. Obviously part of this change is coming from interaction with the world outside. This is why many of the Islamic reformers inside Iran are quoting Hannah Arendt and Karl Popper. Also of course Islamic fundamentalists took a lot from fascism and communism. Fundamentalism is a modern phenomenon. It is not a traditional phenomenon. One of the best reformers in Iran, Akbar Ganji, who was a veteran revolutionary, now refers to Hannah Arendt in his book. Many Islamists refer to Hitler and Stalin. Hannah Arendt becomes important because we do not have theoreticians in our countries who had to deal with fascism. In the West, they dealt with fascism, so we take from them. Where else could we go? So we are reading Hannah Arendt not because the West is so great but because they have been through the experience of fascism and totalitarianism.

In the same interview, you say that you have tried to explain to your American friends that when "the fundamentalists flew into the World Trade Center, it was not merely because of their fear of the US, it was because of their fear of their own people wanting to become more democratic." Could you explain what you mean by this?

I keep having to tell my American friends that the world is becoming smaller and smaller in one sense, so you cannot ignore what happens outside this country and hope to remain safe forever. If you are ignorant of what is happening in Afghanistan, if you think that people can be taken to football stadiums and shot, and it is not going to affect you, you are wrong. We cannot keep thinking that as long as they only do it to their people, we will leave them to it, or that having relations with Saudi Arabia and exploiting Saudi oil will not build resentment against the US.

I try to explain to Americans that supporting democratic aspirations of people in other countries is to their own advantage. Democratic people in other countries criticize the West for hypocrisy in terms of their values; they see people here talking about democracy but not caring about people's human rights elsewhere. That criticism is valid.

Then there are the fundamentalists - like the Stalinists before them - who criticize Western decadence and Western culture, but what they really mean is that women having freedom is not integral to their culture, it comes from the West, so it should be quashed. Every single individual freedom that we talk about in Iran results in us being called spies of the West. They are scared of their own people wanting to be free and wanting to have individual rights, and they attach us to the imperialists. They are also scared of the influence of democratic ideas. Many of these Islamists are not genuine Muslims to begin with. A number of the hijackers involved in 9-11, for example, were having their last drinks in strip-bars before embarking on their suicidal mission. So it is really a political movement that has hijacked a great religion. By saying that, I am not saying that Islam does not have problems, Muslims have a lot of problems and we have to solve them. But it is still so unfair to call these people representative of a religion. Was Stalin representative of the Russian people?

Your book was published early in 2003 in the United States. Did you think at all about how it might be received here at the time?

I am a great pessimist in relation to my own work! I kept telling my editor how I was convinced that this book was going to flop. I got the contract for this book in 1999, well before the events of September 11th , 2001. But when my book was coming out, Iraq was very much on the scene, so I was convinced that nobody would pay attention to it at all.

What amazed me is that my book was successful mostly because of literature. It is so wonderful because I can now go to meetings and people will not just ask me about Khatami and Khamenei. They will tell me instead about having read Lolita. People seem to be interested in the stories that come out from my book because they are not widely known; most of the stories coming out of Iran are about the ruling elite. I wanted to talk about ordinary people. I wanted to tell people my story because I think that totalitarian mindsets confiscate everybody's story and the way to confront this is not to take up guns against them, or to demand regime change, but to tell your own story. So I did not expect the book at all to do what it did.

At one point towards the end of the book, the character you refer to as "my magician" says to you, "You used to talk about writing your next book in Persian. Now all we talk about is what you will be saying at your next conference in the US or in Europe. You are writing for other readers." How much do you think this statement reflects the decisions you made, in the sense that now you write in English, and seem to be writing for a primarily - if not exclusively - American audience? Was the magician prescient in this respect?

Well he had a knack for being prescient!

I live by teaching and by writing; I simply cannot do without either. In Iran, for 18 years a lot of things were taken away from me; going to class was such a joy, and that too was taken away. In my last two years there, when I was teaching this class in my home - which was probably my best class - I was aware that at some point the girls would go their own ways, and I did not have any contacts to be able to find more students, so I would eventually be left with no one to teach. The books that I wanted to write were like the one I eventually wrote here, and I knew that that book would never see the light of day in Iran.

The only way I could go on was to make this decision to come to America, which was very difficult at first. So in one sense my "magician" was right. In another sense, I now discover that when you write, you don't write for Americans or Iranians, you write for soul-mates. I rediscovered so many Iranians all over the world through my book! Many people from Iran, former students, called, or wrote e-mails, or showed up at events in London or New York. I discovered that the act of writing is genuinely universal and you never know who your readers are; so a lot of Americans might hate my book, some may like it, and the same is true of Iranians, and that is the way it should be.

Have you in general been pleased with the way the book has been received?

Yes, I have been ecstatic! I have discovered so many people who love books. I was just at a meeting in Philadelphia with 400 people, and I was telling them that now I feel I should announce at every conference, "Book-lovers of the world, unite!"

Over here, in the US, we should remember that just because there is a democracy, this does not mean that there is not censorship. There is a wonderful book by Diane Ravitch called The Language Police which is about censorship from both extreme-left and extreme-right groups in school textbooks. Many library books are taken off the shelves - even Harry Potter. Public libraries are frequently being shut down because of insufficient funding. I think this should be a matter of concern to us over here.

I did not write Reading Lolita in Tehran to tell Americans how we were deprived; I wrote this book to tell people how important imagination is no matter where you live. Now that this book is out, I hope I will be able to do something about it, to promote my cause here.

What is your next project? Do you have something in mind?

Well there are two projects. One is that I was hoping that the book I wrote on Nabokov would be translated into English as well (from Persian). Through Reading Lolita in Tehran, I am in touch with so many people who are interested in Nabokov, and I would like my book to be made accessible to them in English.

The other project has to do with my mother, who died while I was writing Reading Lolita in Tehran. Before that, when I left Iran, I was so involved with her, I constantly thought about the question of loss. My own mother lost her mother when she was four, and her life was a series of losses. I wanted to write a story about the concept of loss and how you retrieve what you lose through the act of writing. I wanted to reinvent her and to retrieve both what she lost and what I lost in her absence.

Interview conducted by Nermeen Shaikh of Asia Society