The Deepening Japan-Australia Security Relationship: Deterrence against China or Alternatives to the Region?

by Asia Society Australia-Japan Fellow, Kyoko Hatakeyama.

Introduction

Asia's maritime security environment is beset by increasing uncertainty. China not only claims sovereignty in the South China Sea over reefs, uninhabited islands, and maritime territory within its “nine-dash line” but is also strengthening its effective control in an attempt to block coastal states from engaging in fishing and resource-based economic development. This behaviour is also exhibited in the East China Sea. Beijing has repeatedly attempted to enter the Senkaku Islands' contiguous zones and territorial waters, which have been under Japanese jurisdiction since 1972, by claiming sovereignty over the islands. Despite international criticism, China’s efforts to upend the status quo in the maritime domain are intensifying.

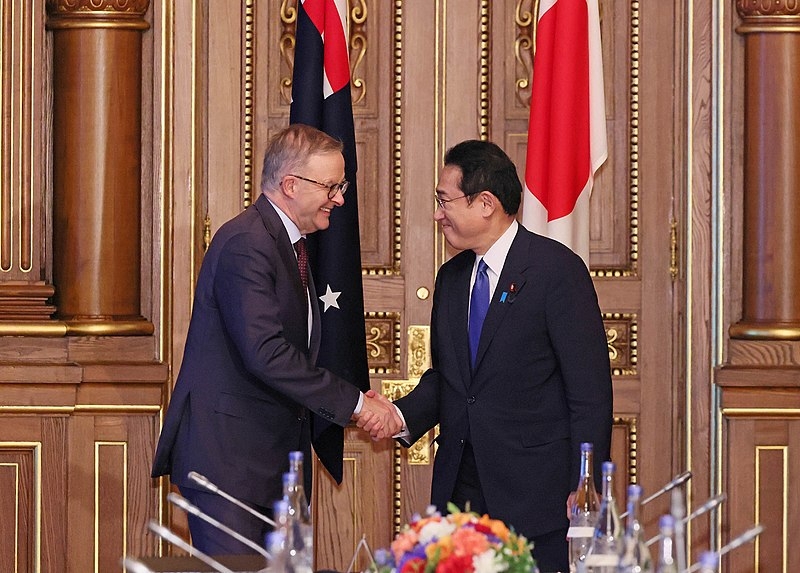

Under these circumstances, the security relationship between Japan and Australia has been growing significantly. Although their security relationship did not deepen straightforwardly, despite the Declaration on Security Cooperation in 2007 and the start of the 2+2 meeting, recent developments in the late 2010s showed that their military cooperation proceeded apace. In particular, the conclusion of the Reciprocal Access Agreement (RAA) and the Japan-Australia Joint Declaration on Security Cooperation in 2022 are remarkable, making their relationship into a "quasi alliance". What factors motivated these states to deepen security-related cooperation? What are the implications of these deepening ties on the regional order?

This article first examines the current regional situation and the deepening Japan-Australia security relationship. Second, it examines factors driving these two states to deepen security cooperation. Third, it analyses the implications of deepening ties between them. Lastly, it concludes that the growing links between Japan and Australia have played a role in maintaining the current regional order. This is followed by policy recommendations.

Evolving Security Partnership

Facing Chinese challenges in the East and South China Seas, Japan and Australia have become vocal, emphasizing the importance of the rule of law and rules-based order at international conferences such as the Shangri-la Dialogue. In January 2018, both states confirmed that they held the same views regarding the Indo-Pacific region and would promote the Free and Open Indo-Pacific Concept (FOIP) and Australia's 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper, respectively.[1]

Based on a common understanding about the preferable regional order, Japan and Australia started to strengthen the security relationship. Remarkably, these states concluded the Reciprocal Access Agreement (RAA) and issued the Joint Declaration, making their relationship more solid. These steps are important because the RAA sets a legal framework for enabling reciprocal visits of either state's armed forces for training and operation purposes. Australia became the first country after the US whose armed forces would be allowed to visit Japanese soil without case-by-case invitations. Institutionalizing the exchanges of visits would facilitate joint training and exercises, thus enhancing their interoperability. It would also promote their cooperation in humanitarian assistance and disaster relief operations.

Second, the 2022 Joint Declaration, which upgraded the 2007 Declaration, advanced the security relationship between the two countries. In the declaration, both states agreed to "consult each other on contingencies" and "consider measures to respond."[2] However, this statement does not indicate that both states agree to defend each other or exercise the right of collective self-defence. Due to Article 9 of the Constitution, Japan is restricted from exercising such a right unless a contingency affects its survival. Nevertheless, the statement illustrates that both states upgraded their security ties to a quasi-alliance level. As institutionalization deepened, joint training and exercises increased their frequency. The Self-Defence Forces (SDF) also protected Australian ships for the first time when they conducted joint training in November 2021.[3] The SDF's protection of foreign vessels, even if in peacetime, is remarkable since such protection was hitherto prohibited as exercising the right of collective self-defence. Australia thus became the second country after the US for which Japan implemented such a mission.

By upgrading and substantiating the security partnership, the Japan-Australia relationship, which hitherto had mainly focused on trade and economy, became more comprehensive. In addition to growing military ties, new cooperation in the hydrogen and ammonia sectors as part of Green Transformation (GX)[4] also reinforced the strength of the relationship. Both states thus became fully-fledged partners.

Factors Underlying Deepening Relations

Behind the evolving regional security relationship between Japan and Australia was their concern over China’s increasing assertiveness. Chinese attempts to change the status quo through coercion in the maritime domain challenges the current regional order underpinned by the US and United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). For instance, in the East China Sea, China continues to intrude into what Japan regards as its territorial and contiguous waters around the Senkaku Islands, which intensified after 2012. Moreover, the Chinese Coast Guard Law of 2021 allowed Chinese Coast Guards to use force against foreign vessels when what it regards as its sovereign rights were violated. In the South China Sea, it took over the Scarborough Shoal from the Philippines and continues to ignore the International Tribunal’s decision that denied Chinese claims of historical rights. China has also been in dispute and even minor conflicts over resource development and exploitation of the South China Sea with other ASEAN states. China’s forceful maritime claims based on its historical rights and its ensuing unilateral attempts to change the status quo increased uncertainty in the region, worrying Japan and Australia.

Second, as if to offset its assertiveness, China has supported the infrastructure development of some Asian states, thus expanding its influence. For instance, as part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) project, China submitted a bid for a high-speed train project between Jakarta and Bandung in Indonesia in competition with Japan. Shockingly to Japan, the long-term largest donor of economic assistance to Indonesia, Indonesia chose China over Japan for the USD 5.5 billion project, partly because Beijing required no funding from the Indonesian government. Similarly, China has provided economic assistance to Cambodia for infrastructure development projects. Not surprisingly, the Chinese debt accounted for most of the bilateral debts owed by Cambodia, which implies growing Chinese influence on Cambodia.[5] China has also approached several Pacific Island states, offering them economic and technical assistance without attaching any political conditions. To dilute Chinese influence, Australia redoubled its efforts to strengthen its relationships with Pacific nations. It announced the Pacific Step-up Initiative in 2016, which aimed to provide financial support to these nations. It also financially supported laying of high-speed internet cables for Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands.[6] Despite these efforts, China successfully concluded a Security Pact with the Solomon Islands in April 2022, shocking the US, Australia, and New Zealand.

Third, Australia was also vexed by China’s attempts to influence and even intervene in its domestic politics. Australia took a balanced policy stance by simultaneously espousing the somewhat contradictory goals of maintaining good relations with China while supporting the rules-based order in the region. The economic benefits derived from China encouraged the Australian government to hold on to its policy of “strategic ambiguity” by separating politics from economics.[7] However, the revelations of Chinese interventions in Australian domestic politics, such as installing an agent within Australia’s federal parliament, gave rise to fear among Australians, driving the country to shift its China policy to a harsher one.[8]

Thus, whereas Japan and Australia’s threat perceptions are not identical, they share a concern over the fate of the regional order as Chinese assertive behaviour challenges a rules-based order based on a free, open, inclusive, and prosperous Indo-Pacific region. A reference to Taiwan’s peace and stability in their meetings also indicated that both states share common apprehensions over Beijing’s coercive attempts to unify Taiwan.[9] Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 fuelled their concern that China may take bold steps over both Taiwan and the Senkakus.

In addition to shared concerns, Japan and Australia became aware that the power gap between the US and China is decreasing. Although the US remains the only state that could compete with China, the overwhelming presence of the US was in relative decline. As a result of China’s rapidly growing economy since it joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, the gap in economic power between China and the US has been lessening rapidly. While the US economy accounted for about 40 percent of world GDP in 1960, this fell to about 24.4 percent in 2019. Meanwhile, China now accounts for 16.3 percent of the world’s economy.[10] Although the US is by far the largest military spender in the world, China’s military spending rose dramatically. Following in the footsteps of the Trump administration that called China a “revisionist power,” the Biden administration has also taken a tough stance against China, committing itself to the defence of Taiwan. It also initiated a high-tech war by restricting the flow of high-end semiconductors and semiconductor manufacturing equipment to China.[11] However, facing the reducing gap, Japan and Australia felt the need to support the US by taking more burden.

Implications of the Close Security Relationship between Japan and Australia

Since the mid-2010s, Australia and Japan have conducted active diplomacy, citing the importance of a rules-based order and the rule of law. In due course, they came to see each other as a reliable partner in underpinning the regional order and felt the need to strengthen their security ties. This thriving relationship implies their willingness to sustain the current regional order and prepare for contingencies by enhancing military interoperability. However, their military capabilities are limited in size, especially as neither is a nuclear military power. Moreover, Japan’s scope for military action is constrained by Article 9 of the Constitution. Although the Legislation for Peace and Security adopted in 2015 enabled the SDF to exercise the right to collective self-defence when a country that has a close relationship with Japan is attacked and the attack would threaten Japan’s survival, the hurdles to exercising such a right remain high. Given these constraints and limitations, these states’ closer military ties neither affect the military power balance in the region nor directly stop Chinese expansionism. Instead, the effect of deepening military cooperation is non-military, in two ways.

First, Japan and Australia's growing military ties sent a message to China that they would not accept China’s forceful attempts to change the status quo by coercing others. While their strategic partnership is equivalent to neither an alliance nor an obligation to defend each other, the conclusion of the RAA and the 2022 Joint Declaration between Japan and Australia—the second and fourth largest economies in the region—illustrates their determination not to acquiesce to China’s attempts. The statement in the Joint Declaration even hinted at the possibility that both states might aid US military action in a contingency over Taiwan or that Australia might support potential military action by Japan over the Senkaku Islands. Their determination will raise hurdles for China to take bold action.

Second, their tie serves to strengthen and underpin the current US-led regional structure. Hitherto, the US has maintained a hub-and-spokes structure in Asia by concluding bilateral alliances with regional states such as Japan, Australia, South Korea, and the Philippines. During the Cold War, it effectively contributed to the region's stability when it was the sole superpower in the Western camp. However, faced with challenges posed by China and a shrinking power gap between the US and China in economic and military terms, the US came to look to regional allies in maintaining the current order. The US Indo-Pacific Strategy published in February 2022 referred to "allies" 24 times and to "partners" 66 times while mentioning China only five times.[12] Given the US inclination to look to allies and partners, the deepening security ties between two spokes, Japan and Australia, helps the US maintain its grip over the region.

For instance, the deepening Japan-Australia security relationship facilitates defence cooperation between the US, Japan, and Australia, leading to regular trilateral military training and exercises between air, maritime, and ground forces. This burgeoning relationship contrasts with the fragile relationship between Japan and South Korea, which suffers from historical disputes over “comfort women” and wartime forced labour. This shaky relationship between the two East Asian allies has long been a source of irritation to the US.[13] In contrast, Japan and Australia’s thriving relationship reinforces the American foothold in the region, making it easier to maintain its presence. The same goes for the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad), consisting of the US, India, Australia, and Japan. Although the Quad does not aim to deepen security cooperation, all member states have agreed to contribute to maintaining a rules-based order, thus becoming a framework for advancing FOIP. This close relationship makes the group particularly operative and solid as it constitutes the core of the group.

However, this active military policy and cooperation may draw China into overreaction. In the 2022 National Security Strategy, Japan pointed out that China “has presented an unprecedented and the greatest strategic challenge” to ensuring the peace and security of Japan and the world.[14] Japan also decided to acquire counter-attack capability and double its defence budget within five years. Australia launched AUKUS, which consists of the US, Australia, and the UK, and decided to introduce nuclear submarines into its own defence capabilities. While such active military policies increase deterrence, it may feed tensions between the US and China. When US speaker Nancy Pelosi for the first time visited Taiwan in 2022, it elicited retaliatory military exercises and the launch of ballistic missiles by China.

Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

Japan is one of Australia’s largest trading partners. Both states are allies of the US. In addition, Japan and Australia share common values, such as democracy and freedom. Yet despite having many common interests, their relationship was confined to the economic realm during the Cold War and the early post-Cold War period. However, in the 2010s, their relationship evolved rapidly, stretching to the security area. The process of deepening security ties culminated in the 2022 Joint Declaration, which provided for consultation between the two states in a contingency. Behind this historic declaration was China's increasing assertiveness in the maritime domain and the lessening power gap between the US and China. Although the security threats perceived by these states were not identical, both Japan and Australia felt the need to underpin the rules-based order in the region.

Japan and Australia’s evolving security relationship affects the regional security architecture in two ways: First, it sends a message to China that they will not consent to China's assertive behaviour and may send forces in a contingency to help US military action. Although this does not alter the power balance in the region, it puts pressure on China to behave. Second, it strengthens the US-led hub-and-spokes structure by providing the US with an additional foothold, making it easier to maintain its presence. However, the overemphasis on this security partnership and their alliance with the US could be counterproductive for regional stability as it may not only provoke China into overreaction, potentially resulting in a contingency over Taiwan or the Senkakus, but also draw them into competition between the US and China.

The goal of both Japan and Australia is not to contain China but to maintain the rules-based order. On the one hand, both states need to continue to put diplomatic pressure on China by establishing ties with like-minded states, including European states, while increasing deterrence through deepening and institutionalizing security ties. Japan and Australia’s attendance at the 2022 NATO summit is a good move. On the other hand, they need to take a middle path in a less confrontation tone. For instance, they should continue to promote a common understanding about the preferable regional order by arguing and persuading other states. Such capabilities were aptly demonstrated in the economic area by the start of Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation in 1989 and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership launched in 2018 after the US left the Trans-Pacific Partnership in 2017.

These states should also continue to provide alternatives to China for regional states through economic assistance. Although the size of the funds each country can provide is smaller than that of China, cooperation with like-minded states—for instance, through the Trilateral Partnership for Infrastructure Investment in the Indo-Pacific between Japan, the US, and Australia[15] — will widen their options. They could also play a political role and contribute to regional stability by mediating and creating peace, for instance, in Myanmar. Playing political and economic roles will not trouble ASEAN and the Pacific nations since they do not have to agonize over a choice between China and the US. As Singapore’s Prime Minister repeatedly said,[16] ASEAN does not wish to choose either China or the US.

While Australia has strong ties with the Pacific nations, Japan has strong connections with ASEAN states. By taking advantage of their respective strength, these states can generate synergy through the division of labour. Pushing the envelope may intensify regional tensions and elicit unnecessary responses. What we need to explore is how to coexist with China peacefully without yielding to its unilateral claims.

[1]Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Joint Press Statement: Visit to Japan by Australian Prime Minister Turnbull,” January 18, 2018, www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/files/000326262.pdf

[2] Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Japan-Australia Joint Declaration on Security Cooperation,

www.mofa.go.jp/files/100410299.pdf

[3] Nihon Keizai Shimbun, November 12, 2021. www.nikkei.com/article/DGXZQOUA12AAN0S1A111C2000000

[4] Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Australia-Japan Leaders’ Meeting Joint Statement, October 22 2022,

www.mofa.go.jp/files/100410296.pdf

[5] David Hutt, “Cambodia not quite yet in a China debt trap,” September 21, 2022. asiatimes.com/2022/09/cambodia-not-quite-yet-in-a-china-debt-trap; Kyoko Hatakeyama, “How and why Japan can be an alternative to China in the Indo-Pacific,” December 16, 2022, www.9dashline.com/article/how-and-why-japan-can-be-an-alternative-to-ch…

[6] Colin Packham, “Australia to use aid funds to build internet connections for two Pacific nations,” May 8, 2018. jp.reuters.com/article/us-australia/australia-to-use-aid-funds-to-build-internet-connections-for-two-pacific-nations-idUSKBN1I9123

[7]Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Australia, “2017 Foreign Policy White Paper,” pp. 46–47, www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/2017-foreign-policywhite-paper.pdf

[8] Andrew Chubb (2022): “The Securitization of ‘Chinese Influence’ in Australia,”

Journal of Contemporary China, Vol. 32, No. 139, 17–34.

[9] For instance, see: Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ninth Japan-Australia Foreign and Defence Ministerial Consultations (“2+2”) www.mofa.go.jp/press/release/press6e_000297.html; Australia-Japan Leaders’ Meeting Joint Statement, op.cit.

[10] Calculated by the author. www.investopedia.com/insights/worlds-top-economies/#1-united-states; Mike Patton (2016) “U.S. Role in Global Economy Declines Nearly 50%.” https://www.forbes.com/sites/mikepatton/2016/02/29/u-s-role-in-global-e…

[11] Hal Brands, “Biden’s Chip Limits on China Mark a War of High-Tech Attrition,” October,10 2022. www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2022-10-09/biden-s-chip-limits-on-ch…

[12] The White House, “Indo-Pacific Strategy of the United States,” February 2022.

[13] Roberta Rampton, “Washington worries Japan-South Korea tensions may worsen: US official” jp.reuters.com/article/us-southkorea-japan-usa/washington-worries-japan-south-korea-tensions-may-worsen-u-s-official-idUSKCN1UR55Y

[14] Japanese Cabinet Office, “National Security Strategy of Japan,” December 2022. www.cas.go.jp/jp/siryou/221216anzenhoshou/nss-e.pdf

[15] Joint statement of the governments of Australia, Japan, and the United States of America on the Trilateral Partnership for Infrastructure Investment in the Indo-Pacific, n.d. www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/files/000420368.pdf

[16] William Choong, Singapore and the United States: Speaking Hard Truths as a Zhengyou

www.fulcrum.sg/singapore-and-the-united-states-speaking-hard-truths-as-…