Briefing Monthly #55 | October 2022

Summit season outlook | The Asian Budget | Xi’s new China | Democracy divide | Inside trade deals | Educating Asia | Food crisis fears | Malaysia votes

Animation by Rocco Fazzari

Asia Briefing LIVE special edition

COMPETITION THEORIES

Are supply chains busted or just being reformed? Is the Quad Asia’s new rock or only just another twinkling star in the diplomatic universe?

Back in-person for the first time in two years, but now online and on the ground with live audiences in both Melbourne and Sydney, Asia Briefing LIVE might have been doing its own version of the Beijing straddle.

That’s the evocative term that Carnegie Endowment for International Peace vice-president Evan Feigenbaum uses to characterise China’s relationship with Russia and the world. Straddling became the conference shorthand for the uncertainty about Asia’s biggest power for business, international relations theorists and the new Albanese government alike, as this year’s discussions occurred amid the anticipation about the new Chinese leadership.

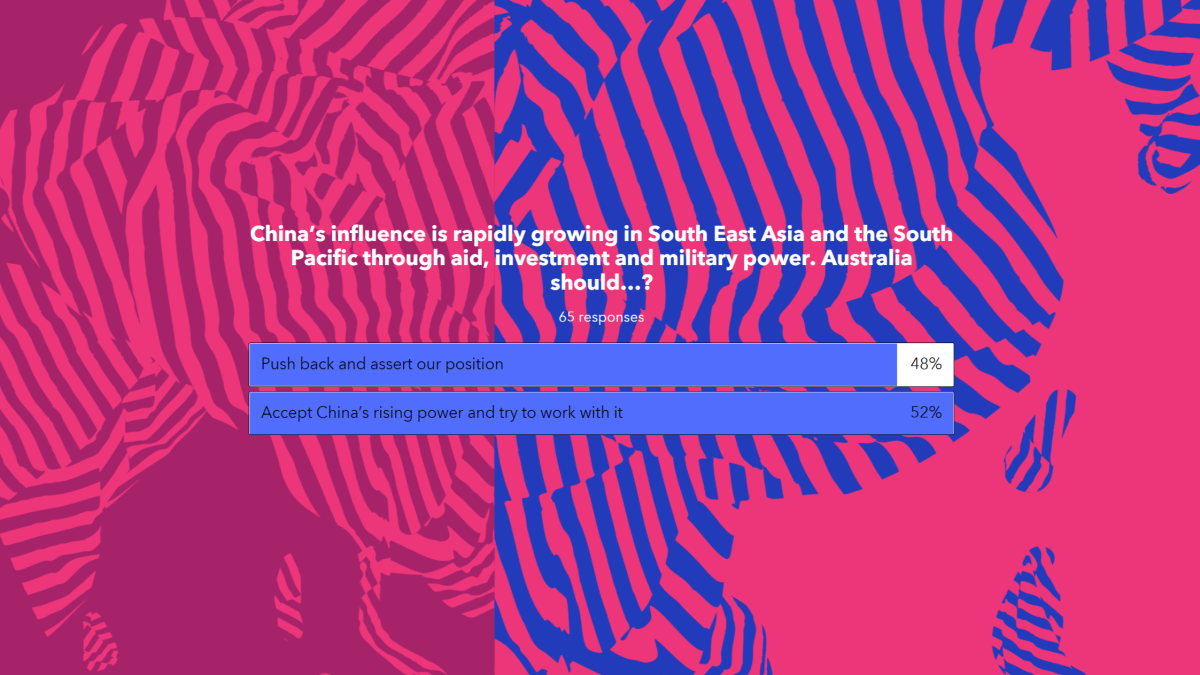

While participants debated the intersection between a world of fragmenting old institutions and the push towards a new decoupling, the audience members did their own straddle. They rewarmed to China as a business opportunity, but favoured greater pushback in response to its rising activity in the near neighbourhood, although perhaps not as much as some others call for.

This month’s Briefing MONTHLY is largely devoted to our annual executive forum for taking the pulse of a complex Asia and Australia’s relationships with it. But first, we recap what the Labor government’s first Budget means for Asian relations. And in ON THE HORIZON, we look ahead to the looming summit season and the election showdown in Malaysia.

BUDGETING FOR ASIA

The Albanese government has stepped up its focus on Australia’s near neighbours with a $1.43 billion increase in development aid over four years to the Pacific and Southeast Asia, but with spending this financial year increasing only slightly to $4.65 billion. The four-year increase is more than what was flagged during the election campaign and will be split between the Pacific ($900 million); Southeast Asia ($470 million); and non-government aid agencies ($30 million).

This possibly marks an end to the pre-Covid aid cutting period under the Coalition government, although aid is still declining overall in inflation adjusted terms and is below Labor Party platform commitments.

The government is also reallocating $500 million in existing aid over ten years to provided extra grant money to the Australian Infrastructure Finance Facility for the Pacific (AIFFP) which will take the facility’s overall lending and grant envelope to $4 billion. The move underlines the AIFFP’s increasingly important role in regional economic diplomacy with Timor Leste airport infrastructure and Fiji bridges being nominated as priority projects.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade funding is undergoing a shake-up with $213 million being reallocated from within existing diplomacy, trade and tourism programs to help fund Labor’s Pacific election promises. Those commitments include aerial surveillance in the Pacific ($30.4 million over four years); Pacific military training ($11.7 million); more Border Force staff ($22.3 million); Solomon Islands policing ($45.7 million); ABC broadcasting $32 million); and more diplomat ($5.4 million). The Pacific Australia Labour Mobility scheme is set to be expanded from 29,000 workers now to 35,000 by the end of this financial year.

Foreign minister Penny Wong said: “Our assistance will help our regional partners become more economically resilient, develop critical infrastructure and provide their own security so there is less need to call on others.”

Three significant newly funded priorities are the just signed green economy agreement with Singapore ($19.6 million over four years); Japan’s 2025 Expo ($100 million); and the 2023 Quad summit in Australia ($23 million).

Overseas student arrivals, largely from Asia, are projected to pick up faster than in the Coalition’s March Budget with net migration returning to at the pre-Covid 235,000 this financial year compared with the 150,000 projected in March. Permanent migration is set at 190,000 including the 3000 new Pacific permanent migrants. Meanwhile in an initiative which may impact on individual university activities, the Australian Academy of Science has been recruited by industry and science minister Ed Husic to lead a $10 million investment over six years coordinating Australia’s scientific engagement with the Indo-Pacific.

The defence Budget is little changed reflecting the reviews now under way which will report next year. But the Budget papers show the fall in the Australian dollar has increased the cost of existing defence equipment by $2.8 billion over four years. This compares with a projected saving of $1.1 billion in the last Budget due to a then higher $A. Meanwhile higher economic growth and inflation means spending has dipped below the targeted minimum two per cent of gross domestic product.

In another Budget related development Treasurer Jim Chalmers has stepped up warnings about the need for an intervention in the gas market to curb rising prices. Japanese officials have been increasingly strident about how such a move would damage Australia’s reputation as a reliable gas supplier including most notably during the recent visit by Prime Minister Fumio Kishida to Australia to sign an updated security agreement.

NEIGHBOURHOOD WATCH

Illustration by Rocco Fazzari. View the full animation here.

MANAGING CHINA

Chinese President Xi Jinping’s choice of six absolute loyalists to stock his kitchen cabinet at the heart of the Chinese Communist Party has underlined the Asia Briefing LIVE discussions about how he is now the key figure in a decoupling world.

Speaking before the unveiling of the new Politburo standing committee members, Asia Society president and chief executive Kevin Rudd declared that Xi was now assuming a role co-equal to Mao Zedong. This was “pointing very much in the direction of Xi Jinping being numero uno, dos and tres and the rest is all kind of detail,” he said. Rudd argued that in Xi’s new era of socialism with Chinese characteristics, his Congress work report had underlined how China was shifting further towards a state driven economy and ideological struggle against outside forces.

“I see no evidence that there will be a return to the market. I see more evidence of a doubling down in support of the party state, and through such doctrines as the doctrine of common prosperity, that the shift to the left in economic policy is going to continue.” Rudd continued, with the one exception that there still may be an effort to internationalise the currency to shelter China from potential future international economic sanctions.

The discussions about living with an increasingly one-person state in China ranged widely from relative optimism to growing despair. Asia Society Policy Institute senior fellow and Institute of South Asian Studies professor C. Raja Mohan maintained it was still important in strategic planning to look ahead to a China after Xi. But Asia Society Australia policy director Richard Maude declared that the Biden Administration idea of achieving “competition without catastrophe” in China relations increasingly appeared to be elusive.

Amid this growing sense that Xi was crafting a one person state, Macquarie University associate professor Courtney Fung said it was still important not to let the orchestrated theatre of the party congress to create the impression that everything in China flowed from the top. She pointed out, for example, that there had been differences of purpose and implementation surrounding Xi’s Belt and Road Initiative over several years as competing interests still tried to implement it in ways that suited them. “As much as this language is set from the top,” she said, “A number of players will come in to try and fill that out and interpret and sort of bring that vision into reality.”

Taking up this uncertainty about implementing Xi’s views, Lowy Institute senior fellow Richard McGregor suggested it would require a major crisis for people with different views to Xi to find the space to organise. But he said he was less pessimistic about the decline of the private sector in China despite Xi’s rhetorical support for a more state-led economy. “I’m always a little bit leery about being too bearish on the Chinese economy. I think there's often a bit of wish fulfillment in that. They do have a great deal of flexibility and plus they do have a fantastic entrepreneurial culture. Part of that entrepreneurial culture (is) dealing with officialdom and being smart enough to get around of it.”

Nevertheless, as the China analysts tended to focus on Xi’s role in intensifying great power rivalry, the deputy executive director for research at Indonesia’s Center for Strategic and International Studies, Shafiah Muhibat, provided a reminder that smaller countries were nervous about actions by both China and the US. “There are competing narratives of what the Indo Pacific is and Southeast Asia has been the receiving end of these competing narratives. None of this seems to really serve Southeast Asia's interests, yet massively impacts the region.”

WASTING ASSET

In an indicator of the tense time ahead during the Asian summit season over Russian and Ukrainian participation, Vladimir Putin’s Russia made its presence felt in this year’s conference like never before. Evan Feigenbaum questioned the much repeated idea that China and Russia have embarked on a “no limits relationship” which has hastened global fragmentation. He argued that while China and Russia had a shared interest in counterbalancing American power, Russia was actually a “wasting asset” for China’s long-term rivalry with the US.

Feigenbaum said: “China has a $15 trillion economy, and in no sector and in no area is commercial or financial relations with Russia more important to China than global market access. So, they've had to basically do what I call the Beijing straddle, where they tack uncomfortably back and forth between their strategic and their operational and tactical interests.” Meanwhile Raja Mohan underlined how the idea of a binary fragmentation was also being challenged in India where the country was inclined to tilt more to the west but was still tied to Russia for energy and military supplies. This Indian straddle “comes from the fact we have a historic relationship with Russia, which actually developed when China and Russia were at each others’ throats in the sixties. So historically, we saw Russia as a balancer against China,” he said.

Feigenbaum and Mohan both argued that Russia’s relative decline as a world power despite the Ukraine showdown could be seen in Central Asia where former Soviet states were trying to assert themselves against being geostrategic pawns for both Russia and China. He said: “I really want you to think about Central Asians being at the center of the story rather than just a playing field for contestation, because I think that's what's changed radically in the region over the last few decades, to which Mohan replied: “I think Russia's action (in Ukraine) has actually weakened it in Central Asia, and I think it opens up that space. Turkey's doing a lot more there today … And you'll have a lot more possibilities for rest of Asia to engage in Central Asia.”

DEMOCRACY DIVIDE

The Biden Administration’s new national security strategy may have provided a new pathway for US engagement in Asia by shifting from the previous approach of dividing the world into autocracies and democracies. The apparent change provided the fulcrum for the final panel discussion about how to manage this faultline in regional diplomacy which Australia is particularly trying to step around.

Richard Maude characterised this as a Washington straddle as the US started to realise that the earlier emphasis on democracies standing up for themselves was not striking home with countries which could be allies in its rivalry with China. “I think many countries in Asia don't like the competition of systems framing. They regard it as automatically exclusionary of China. Many of these governments are hardly of liberal ideology and practice themselves,” he said. For Australia this democracy divide was providing an insight into what might happen in a war over Taiwan: “If Australia chose to support the United States in such a contingency, then we shouldn't and couldn't expect most of Asia to follow.”

Former Singapore diplomat Bilahari Kausikan said the US framing of national interest around democracy was simplistic and had been shown to be so by the US having shared concerns with Vietnam and India over China’s assertiveness. “I don’t think India joined the Quad because it was a collection of democracies. It has specific reasons for joining it which has to do with security concerns, not these broad ideological ideas … Not everybody will find every aspect of Western democracies attractive. In fact, I would not consider it an attractive model for Singapore.” Likewise Indonesian ambassador to Australia Siswo Pramowo said the US needed to focus more on common interests and partnerships rather than faultlines. And he tellingly pointed out that when Indonesia needed vaccines during the Covid pandemic, its citizens didn’t focus on where the vaccine come from. “We are not going to question is it made by the autocracy or is it made by the democracy? The first question raised by people was ‘Is it halal?” So, things are so different.”

While the Albanese government has reverted to a more traditional Australian diplomatic position by avoiding ideology in its diplomacy, Lowy Institute Southeast Asia program director Susannah Patton pointed out that there had been slightly different rhetoric about democracy from foreign minister Penny Wong (more cautious) and defence minister Richard Marles (more ambitious). Nevertheless, the government has asked a parliamentary committee to examine how Australia can support democracy in the region, at least from a technical assistance perspective. “I think there’s a case to be made that by engaging more proactively with the civil society or opposition groups, you actually give yourself greater political space to engage with the official governments as well,” Patton argued.

MARXISM 101

With the ABL conference being held in the days before the new Chinese leadership was revealed, the speakers provided a crash course in how to interpret the ideological underpinnings of the Chinese Communist Party.

Kevin Rudd kicked this debate off by arguing that Marxist Leninist ideology was still the “code language” through which the CCP transmitted its view to the rest of the country. “In this document you see a series of statements reaffirming the centrality of a Marxist worldview, the centrality of the Marxist analytical tools of dialectical materialism and historical materialism as the analytical vehicles through which to observe reality,” which was a shift from recent decades when Marxist Leninism was just “elegantly draped” across a “rambunctious, riotous, rollicking semi-free market economy,” Rudd argued saying Xi’s latest work report had caused him to “double down” on the importance of Marxist theory.

But Lowy Institute senior fellow Richard McGregor questioned whether Marxism was crucial to understanding China: “The ideology stuff is not overcooked because the system is full of it, but I think it’s more about an ideology of power, and that’s Leninism. As to all this stuff about dialectics and the like, I think that's the sideline.” Likewise, Raja Mohan, declared to some laughter that he had a background in communism, but now didn’t take talk of Marxism as a driving force in China too seriously: “A lot of it is propaganda junk, you know, so you should believe every word that comes out of the mouth of party hacks.” And Courtney Fung argued that it was just as important to pay attention to nationalism as the prevailing driving force in Chinese politics beyond ideology. She said: “I think in a lot of ways it’s the use of these nationalistic pressures to help negotiate China's foreign policy space and also to try and manage movements within the economy, appropriate types of spending. We have to look at the other types of tools that the party uses to try and guide public opinion and public behaviour and nationalism can be one of those very important tools too.”

ASIAN NATION

Illustration by Rocco Fazzari. View the full animation here.

POLLS APART

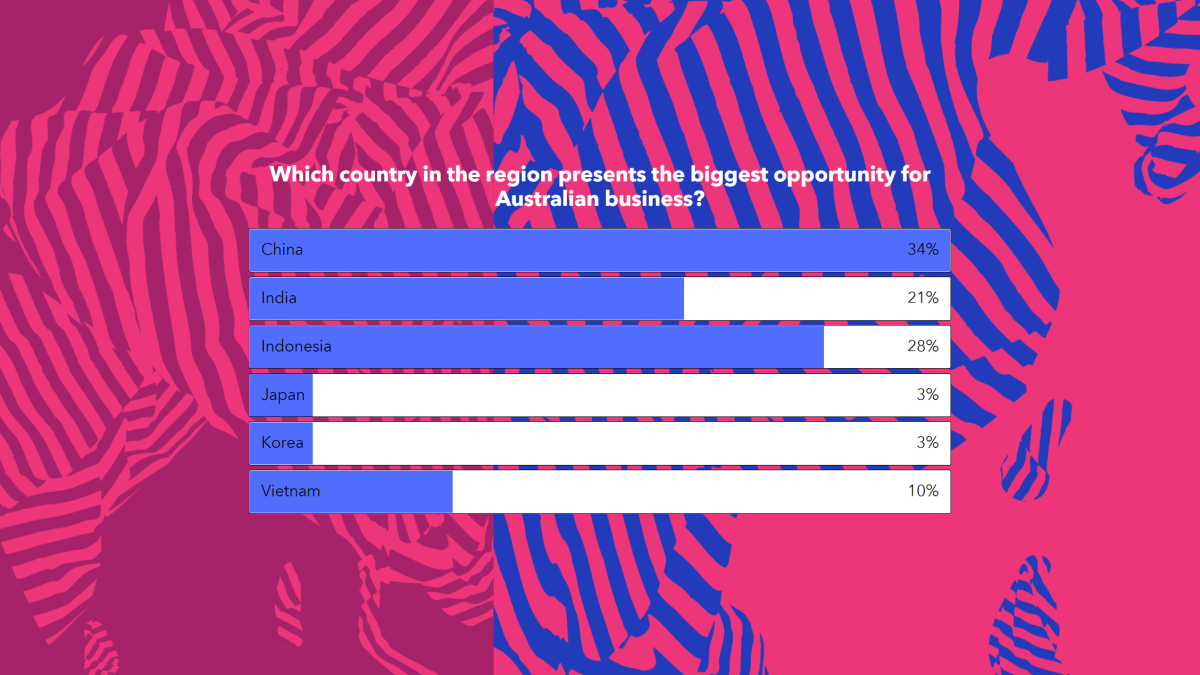

The Asia Briefing LIVE audience has strongly backed bilateral diplomacy as the primary tool for Australian engagement with Asia under the new Labor government and shown a somewhat more optimistic attitude towards business prospects in China.

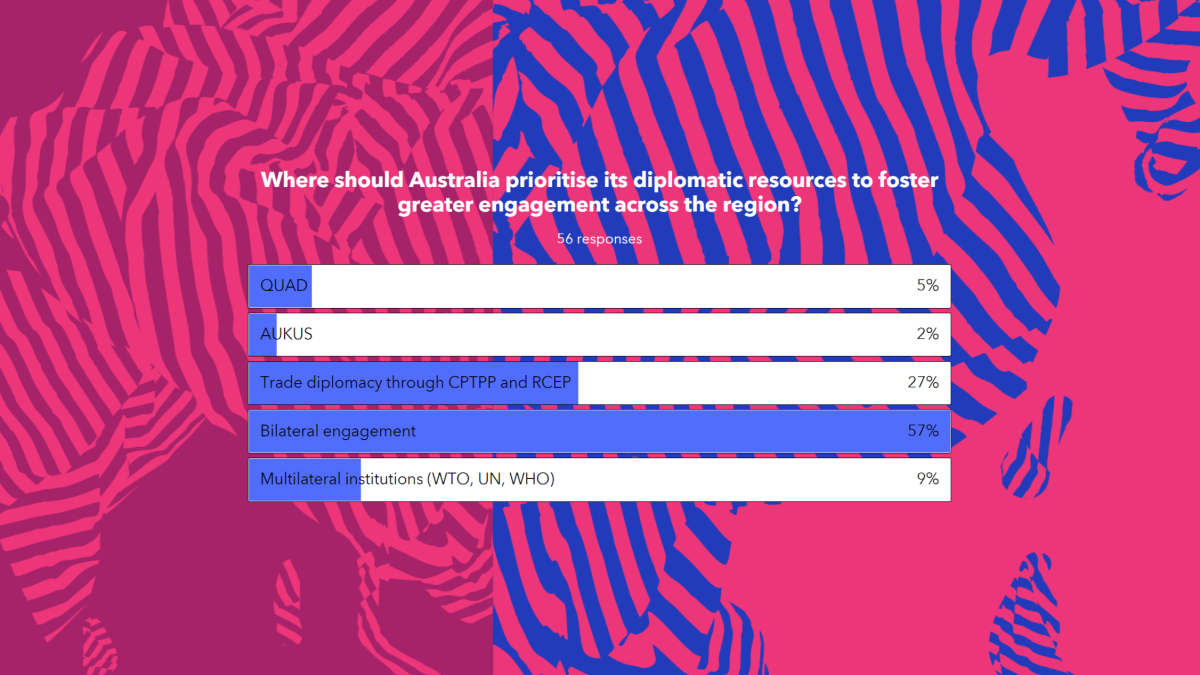

In a sharp shift from last year when 40 per cent of respondents backed trade deal diplomacy as the best path for engagement, this year 59 per cent backed bilateral diplomatic engagement. The Quadrilateral Security Initiative (Quad) lost ground, while the AUKUS submarine partnership and multilateral institutions again won little support. (see DATAWATCH below). This preference for diplomacy aligns well with the Albanese government emphasis on bilateral visits to Southeast Asian and South Pacific nations in its early international relations, although the focus is about to shift with a series of three international and regional leaders’ summits in November. (See ON THE HORIZON below).

Meanwhile China made a significant recovery as the country which offers the best opportunity for Australian business after declining sharply last year as the government stepped up promotion of diversification to countries including India, Indonesia and Vietnam in response to China’s coercive trade sanctions. Thirty-four per cent of respondents chose China as offering the best opportunity ahead of Indonesia and India, while Vietnam continued to outshine the larger and older business partners in Japan and South Korea. But in a contrary turn on China, the audience was almost neatly split on whether Australia should accept China’s rising power in the region or push back against it. Over the five years the ABL conference has been held, support for accepting China’s rising power has fallen from 90 per cent to 51 per cent.

CHINA: A NEW PATH

One of Australia’s senior trade negotiators has expressed growing confidence that Australian business has learnt how to negotiate the pitfalls of Chinese trade sanctions by diversifying.

Echoing the mixed attitude to China in the polls, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade regional trade agreements chief Elizabeth Bowes said China would remain an important trading partner for Australia but “businesses are beginning to adapt to the changing geopolitical environment”. After the anxiety generated by the trade sanctions on exports to China valued at about $20 billion in late 2020, exporters had pivoted to new markets and were now seeing bigger issues of concern than access to China. “Through our market diversification strategy, we have created opportunities for businesses impacted by certain Chinese trade measures to enable them to find alternative markets, but also to be more cognizant of the risks in dealing, not just with China, but more generally with the global risks in the market,” Bowes said.

Meanwhile Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet deputy secretary Katrina Cooper said the new government had been seeking to stabilise the bilateral relationship with meetings with China’s foreign and defence ministers but: “It will take time. It will be step by step.” She said the government was keen to see trade flowing again and to find areas where cooperation was mutually possible.

EDUCATION NATION

Southeast Asian opinion leaders see education as one of the strongest Australian soft power assets in the immediate region as the Albanese government tries to craft it regional foreign policies around shared interests.

Ambassador Siswo Pramono, who studied in Australia, described his particular generation as “made in Indonesia and designed in Australia” which he said was an important pathway for Australian engagement as Southeast Asian countries sought more specialist education. He said the largest share of Indonesian foreign students were still choosing to go to Australia rather than America. “It’s cheaper and easier to get there and still in Asia,” he said putting this education connection into a bigger framework of being “an important factor why Indonesia and Australia should work together as an economic powerhouse.” Expanding on this favoured arm of Indonesian thinking on the bilateral relationship, he said “we have laborers where you have technology, combined together as one economic powerhouse you (we) become a second China … skilled labour, professional training will be very important. This is the important point for future cooperation.”

Bilahari Kausikan supported the idea that technological education created the potential for stronger bilateral bonds with Southeast Asian countries, particularly in environmental areas. He questioned why there were doubts in Australia about the quality of cooperation with regional countries declaring that Australia was part of the region and understood the region better than some other dialogue partners of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. “You are here. You have a long relationship with all of us individually as well as collectively. I find it a bit of a peculiar question. I think it’s a natural partnership.”

DEALS AND DOLLARS

Illustration by Rocco Fazzari. View the full animation here.

LEAVING GENEVA

Former deputy US Trade Representative and Asia Society Policy Institute vice-president Wendy Cutler has declared an end to a half a century where trade agreements tended to be crafted within an unofficial consensus that they would be eventually integrated into a global rules-based (trade) order. She argued that despite the concerns that the shift towards bilateral trade deals in the 1990s would undermine the multilateral or World Trade Organization-based system, there had been underlying confidence they would eventually be unified and push the multilateral system forward.

But she now looks at the latest trade negotiations or discussions amongst countries and sees little expectation there is any real pathway to the sort of open architecture needed to allow multilateralisation. “When I look at the new groupings and the basis upon which groupings are being established or the type of work that's taking place in certain coalitions of countries, it doesn't seem to be that the focus is let’s make the rules and then move it over to Geneva … This is a very kind of different world in terms of who you want to be in this club and who you don’t want to have in this club,” said Cutler.

But she noted that while there was growing enthusiasm for reshoring of production or friend-shoring with trusted partners as the US tried to rebound from excessive dependence on globalised manufacturing, there were also emerging practical difficulties. US trade partners were starting to complain that if they were forced to move production to the US by new Biden Administration legislation, they would face their own backlash from their own voters. Nevertheless, she argued that the relatively new Indo-Pacific Economic Framework being pushed by the US, had some potential for getting a large number of countries to cooperate just as the original Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) group did.

TRADE MASTERCLASS

While the conference may have been more focused on the big geopolitical issues than commercial matters, thanks to an audience question the audience got an impromptu lesson in trade negotiations just when opportunistic bilateral deals are becoming more important.

Wendy Cutler, a former US Deputy Trade Representative, revealed her most difficult job had been to negotiate the US trade agreement with Korea in 2007 when she discovered how much preparation the other side had done. “I remember sitting down with the Koreans and they had kind of mapped out every trade agreement that we had done to date, provision by provision, and basically asked us if they could get the weakest provision that we agreed with Oman or Bahrain or whatever.” She said a lot of people had told her she was wasting her time talking with the protectionist Koreans, but she quickly discovered they wanted a deal. “I think the recipe for success in a trade negotiation … is that if you have a partner that wants to be at the table and has the same objective as you have and Korea did, they wanted a free trade agreement with us for their own reasons, not because the US was pressuring them to do it.”

DFAT negotiator Elisabeth Bowes revealed that while the United Kingdom had really wanted a bilateral agreement with Australia last year, its negotiators came to the table with “hangovers” due to withdrawing from the European Union. “Sometimes you can underestimate your negotiating partner because you think you come from the same culture - such as us or the United Kingdom - but everyone has different approaches and different cultural approaches as well that really have to be taken into account,” said Bowes. She said Australia faced particular challenges negotiating with Southeast Asian countries on regional deals because they wanted to negotiate as an Association of Southeast Asians Nations (ASEAN) bloc. Australian negotiators had to understand trade relations between individual regional countries because they could cloud Australian negotiations with a single country even when there were no bilateral issues at stake.

Meanwhile Michaela Browning, Google Asia Pacific policy vice president but a former Australian trade negotiator, said her experience dealing with the concept of an internet enabled refrigerator during the negotiations on the 2005 US-Australia trade deal had been an insight into the challenges of the now established digital trade. “It’s so important that people understand as negotiators the technology and what that means … we need to keep abreast of how the technology is evolving to make workable solutions,” Browning said.

FOOD FOR THOUGHT

Asked what the biggest threat to global peace was, the ABL audience bypassed the obvious tensions over Ukraine or with China, to settle decisively on food insecurity and energy costs (see: DATAWATCH below). But this only highlighted the downbeat views about the capacity of the world’s top economic institutions to manage this challenge. Fresh from observing the IMF-World Bank semi-annual meetings in Washington, Wendy Cutler said those institutions and the Group of 20 (G20) economic powers were showing little of the capacity to deal with the world’s current inflation challenge that they had shown during the 208 Global Financial Crisis. “It was more of a blame game than kind of a roadmap for coordination and cooperation and so that's pretty serious.”

Bloomberg Australia and New Zealand economist James McIntyre expressed concern that the G20 countries (especially in Europe) were more capable of dealing with the food and energy price rises in their own jurisdictions than in the developing world where the consequences could be more severe. “So that then leads to much, much more instability and then broadens some of the security challenges beyond what we’re seeing within the Russia and Ukraine sphere … food insecure countries have much, much bigger impacts and security challenges that require interventions and quite frankly require an extra bit of policy focus from G20 members as through all of the forums,” he argued.

DATAWATCH

This year's Asia Briefing LIVE audience poll results.

DIPLOMATICALLY SPEAKING

I don’t think we ever want to get into a situation where we again are so reliant on China.

- Trade minister Don Farrell, ABC Country Hour, October 11

China continues to be our largest trading partner. And not only are they our largest trading partner but the value of the products that we sell into China has, in fact, been increasing. So, it's not all bad news on the China front.

- Farrell, ABC Radio National, October 12

It seems we’re not moving fast enough, not as fast as China would expect. It’s improving but on a slow, bit-by-bit basis. Somebody may say that Australia can co-operate with many other countries. Congratulations. But in my view, you cannot find any other partner like China.

- China’s ambassador to Australia, Xiao Qian, Sydney Morning Herald, October 13

Australia and China have taken important steps to stabilise the relationship, including through a range of constructive ministerial engagements. This will require continued engagement and goodwill on both sides.

- Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade spokesperson

ON THE HORIZON

Picture: www.g20.org

ROCKY PATH TO THE SUMMIT(S)

Good things may not come in threes as Asian leaders prepare for an unusually packed summit season this year with the addition of the Group of 20 meeting in Indonesia. Each gathering seems set to be overshadowed by external challenges which will raise questions about the efficacy of the region’s diplomatic architecture. So bilateral meetings will be the main focus with Prime Minister Anthony Albanese attending all three for the first time and possibly seeking his first meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping.

East Asia Summit: Phnom Penh, November 12-13

The 17th gathering of what was once the region’s pre-eminent meeting of now 18 countries will initially be under pressure over the inability of Southeast Asian leaders to make obvious progress on the Myanmar impasse almost two years after the coup. Even the modest efforts by Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) chair and Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen to negotiate with a fellow authoritarian regime have been spurned. ASEAN leaders meet before the 18 EAS leaders and will need to make some progress on Myanmar to bolster their claims to a central role in regional diplomacy amid the emergence of new institutions such as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue. But the EAS, which includes Russia, will then be under pressure over the Ukraine war with Ukraine expected to sign the ASEAN foundational Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in a snub to Russia. Indonesia takes over next year which may introduce more momentum into ASEAN.

Group of 20: Bali, November 15-16

The 20 member G20 will hold its summit in Bali on November 15-16 where geopolitical tensions over Russia and China may be more evident due to the participation of a broader range of large countries from around the world. The challenges for this year’s chair and Indonesian President Joko Widodo were underlined at the recent International Monetary Fund meeting where Indonesia issued a summary statement after the G20 finance ministers again could not issue an agreed statement. The 23-year-old G20 was elevated to a leaders’ level annual summit in response to the 2008 global financial crisis but has so far played a much less significant role in responding to the current emerging global crisis over energy, food and inflation. With India taking over the chair from Indonesia this was once seen as a chance for Asia to place a stamp on one of the world’s key diplomatic institutions, but that appears to be fading.

Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation: Bangkok, November 18-19

This is the 30th leaders’ summit of the 34-year-old, 21-member group which once predated the EAS as Asia’s pre-eminent gathering. But these days it is challenged by the shift to bilateral trade deals and the new trade pacts such as the 17-member Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership and 11-member Comprehensive and Progressive agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). More importantly the US – which is not a member of those two pacts – is now pushing its own Indo-Pacific Economic Framework as an APEC-styled cooperative group with the exception that it does not include China. Australia has a lot invested in APEC as one of its founders. But the summit has had a troubled recent past with US-China tensions in 2018 (PNG) and domestic political issues in 2019 (Chile) and 2020 (Malaysia). Curiously President Joe Biden will not attend the Bangkok summit due his daughter's wedding even though the US is the APEC chair country next year. APEC meetings have also been upset by the Russia-Ukraine war issue this year and Putin’s attendance may depend on what happens with the G20. Thailand has asserted its diverse diplomatic priorities by inviting the leaders of France, Saudi Arabia and Cambodia as its guests.

MALAY DIVIDE

An election meme targeting the new young voters.

Malaysians go to the polls on November 19 amid a remarkable age divide. The world’s oldest serving recent leader – Mahathir Mohamad – is running yet again alongside several other old political warhorses just as five million people under the age of 21 will be eligible to vote for the first time.

Meanwhile the country’s dominant Malay population which was once largely politically unified under the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) umbrella has fragmented into several political groups raising doubts about whether there will be a clear majority with one third of electorates held with narrow margins.

Voters will be electing 222 members of the national parliament and three state parliaments in the first election since an UMNO-led coalition was thrown out of office in 2018 for the first time since independence.

Mahathir, 97, who was the UMNO prime minister for more than two decades last century, led the opposition Hope coalition to victory in 2018 alongside long-time rival and former ministerial colleague Anwar Ibrahim. But the coalition fragmented in 2020 and he was replaced by a fellow UMNO rebel Muhyiddin Yassin. After more tensions Muhyiddin was replaced by the incumbent UMNO Prime Minister Ismail Sabri Yaacob, who is trying to hold his factionally divided party together long enough to win a new election mandate from an early election.

All these old politicians are still running in a nation where a new cohort of young voters may be looking for something new.

ABOUT BRIEFING MONTHLY

Briefing MONTHLY is a public update with news and original analysis on Asia and Australia-Asia relations. As Australia debates its future in Asia, and the Australian media footprint in Asia continues to shrink, it is an opportune time to offer Australians at the forefront of Australia’s engagement with Asia a professionally edited, succinct and authoritative curation of the most relevant content on Asia and Australia-Asia relations. Focused on business, geopolitics, education and culture, Briefing MONTHLY is distinctly Australian and internationalist, highlighting trends, deals, visits, stories and events in our region that matter.

We are grateful to the Judith Neilson Institute for Journalism and Ideas for its support of Briefing MONTHLY and its editorial team.

Partner with us to help Briefing MONTHLY grow. For more information please contact [email protected]