After the White Paper: Australian Foreign Policy in a COVID-19 World

Australia is grappling with a toxic mix of foreign policy challenges that were either absent or still distant objects on the horizon when the Turnbull Government’s 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper was drafted.

In a competitive field, four such challenges stand out.

First, a smashed global economy from the wrecking ball that is COVID-19.

Second, deteriorating Australia-China ties marked by a sharp clash of interests and values.

Third, faster change in global order, driven by China’s power and assertiveness and the unilateralism and nationalism of “America First”.

And, fourth, the collapse of U.S.-China relations.

The Morrison government is blunt in its appraisal. The “contested and competitive” world described in the White Paper has given way to a grimmer outlook: “poorer, more dangerous and more disorderly”.

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade believes the COVID-19 pandemic is not altering “the currency of Australia’s long-term international objectives outlined in the Foreign Policy White Paper”.

But this is policy at the headline level. The deeper story is more complex: inevitably, Australian foreign policy is evolving to meet new realities.

COVID-19 is a clarifying moment, pushing Australia to confront not just the immense impact of the pandemic but the broader deterioration in the nation’s external outlook since the White Paper was published.

Recent government policy announcements and speeches demonstrate this new dynamic at work. This is particularly so for the three White Paper policy priorities under most challenge: “openness”, multilateral rule-building, and Australia’s efforts to support a balance of power in the Indo-Pacific “favourable to our interests”.

These evolving policy responses have not been brought together in a unified White Paper update, as the recent Strategic Update did for defence policy. After three relentless years of change there is an argument for doing so.

And while policy is adapting in sensible ways, it is also reasonable to ask whether more needs to be done.

Openness

Australia’s commitment to economic “openness” — a central conceptual pillar of the 2017 White Paper — is not being abandoned. But it is being modified to better protect Australia against future supply chain disruptions and the security and economic risks that come with China’s dominance of many industries. You won’t, for example, find the term “economic sovereignty” in the White Paper, but it is now repeatedly invoked as a new national priority.

The government recognises that globalisation needs a work over. So far, at least, “balance” is the operative term – policy must evolve to ensure Australia can make or obtain what it needs in times of crisis or because of “market concentration” (read: China) while, in the words of Trade Minister Simon Birmingham, “not engaging in a wholesale retreat from the openness that underpins our prosperity”.

A hard look at what products Australia really must be able to make at home is underway. The government has been clear this list won’t be endless: Much of what we consume does not need to be made here and many of Australia’s supply chains for manufactured and other goods have recovered reasonably well (some, notably aviation freight, with government help).

A return to large-scale industrial subsidies or market interventions does not look likely, although tax incentives look to be on the table for investment in advanced manufacturing.

Rather, the government says the future of manufacturing will be “enterprise driven,” with policies to boost Australia’s “comparative and competitive advantage” by lowering manufacturing costs (energy, for example), prioritising technology and skills, and removing regulatory impediments.

Australia will continue long-standing efforts to win preferential market access for Australian exporters through bilateral and plurilateral trade agreements and to push back against protectionist sentiment at home and abroad. Here the White Paper trade agenda remains largely intact.

Simon Birmingham, for example, maintains that “most protectionist arguments are nothing but an illusion, promising a return to a nostalgic but mythical past”. And Australia is pushing on with a still-hefty rule-setting and trade liberalisation agenda, including the Australia-EU and Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) negotiations.

Holding on to the idea of openness, even if more caveated than in the past, makes sense for Australia given the structure of its economy and international trade.

But the headwinds are stiff. Even before the pandemic, automation, new technologies like 3D printing, rising labour costs in China, and the U.S.-China trade war were re-shaping globalisation and encouraging “near-shoring” and “re-shoring."

The pandemic has sharply reinforced concerns in the United States about the economic and national security risks of the concentration of many global supply chains on China.

Indeed, it’s hard to overstate the shift in the United States on globalisation, encapsulated as much in Joe Biden’s “foreign policy for the middle class” as it is in President Trump’s visceral dislike of trade deals and desire to bring US manufacturers home.

The intellectual challenge to globalisation in the United States now goes well beyond free trade to encompass previously untouchable elements of American capitalism. Efficiency, profit and share prices, for example, are now weighed against national economic security, employment and community cohesion, and are found wanting.

China, too, is adjusting its policy settings. Its new “dual circulation” concept, admittedly still vague in its intent, is described by some analysts as a form of “hedged integration” with the global economy, in which more growth is generated by domestic consumption. This consumption would be fed as much as possible by Chinese production, “all while finding ways to reduce reliance on external inputs.”

This won’t be easy to achieve. But any plan to give local producers the lion’s share of China’s giant consumer market inevitably will stoke global economic tensions.

Multilateralism and rules

The post-war system of international institutions and rules built to guide and promote global cooperation was already sending out distress signals in 2017, when the White Paper was being drafted.

The political and economic effects of globalisation and the sheer complexity of many current global challenges, like climate change, were testing the cohesion and effectiveness of the system. Chinese revisionism and increasing use of coercive power and US neglect and unilateralism were emerging as double blows.

Still, the White Paper argued it was in Australia’s long-term interests as a middle power to do what it could to encourage effective multilateral institutions and “the international rules that support stability and prosperity”.

This model has survived a recent government audit of Australia’s interests in the multilateral system, notwithstanding the prime minister’s dig earlier in the year at “negative globalism.”

In a speech on 16 June announcing the government’s response to its audit, Foreign Minister Marise Payne was again clear that “Australia's interests are not served by stepping away and leaving others to shape global order for us.”

Without naming either country, Prime Minister Morrison has some parallel advice for China and the United States: “neither coercion nor abdication from the international system is the way forward.”

Inevitably, though, beyond policy at the headline level, the White Paper agenda is being adapted to new realities.

First, a much stronger emphasis on effective and accountable international organisations that are “free from undue influence” (the Morrison government was deeply unimpressed by the World Health Organisation’s early handling of the pandemic). The government also wants international institutions to have a stronger focus on the Indo-Pacific.

Second, Senator Payne’s speech reflects an even stronger values frame to Australia’s engagement with the multilateral system and the development of new rules.

Third, priorities for “better targeted” Australian engagement in the multilateral system reflect the importance the government places on recovery from the pandemic, building resilience to future global shocks, and responding to Chinese revisionism.

These priorities encompass rules to “protect sovereignty and curb excessive use of power,” international standards related to public health and the global arteries essential to economic recovery (such as telecommunications and transport), and the norms underpinning human rights and the rule of law.

And, fourth, more emphasis on working in smaller coalitions or groups, including ones that are values or democracy-based.

Senator Payne’s speech was not intended to cover the waterfront of multilateral issues. Still, it is notable that some White Paper priorities, such as climate change and disarmament, were not mentioned at all.

China-U.S. competition and the inefficiency and gridlock of parts of the multilateral system will continue to push Australia into mini-lateral groups of one sort or another. This is neither entirely new territory – Australia has long-worked in issues-based coalitions – nor an unreasonable response to current circumstances.

But there are risks. Over-emphasising “trust” or values-based coalitions could alienate some important partners or accelerate multilateral “bloc-ism.” And some issues, like climate change, can only be effectively tackled with China in the room.

A balance favourable to our interests: Australia in the Indo-Pacific

The White Paper committed Australia to more deliberate, whole-of-government efforts to shore up Australia’s influence in the Indo-Pacific and help build a regional order in which “the rights of all states are respected” and the nation’s ability “to prosecute our interests freely is not constrained by the exercise of coercive power”.

Events since the publication of the White Paper – China’s militarisation of the South China Sea and zero-sum pursuit of influence in the Southwest Pacific, the use of the Belt and Road Initiative to advance political and security interests in Southeast Asia, and Beijing’s ruthless crushing of “one country-two systems” in Hong Kong – have reinforced Australian concerns about China’s regional ambitions.

A “durable strategic balance in the Indo-Pacific” continues therefore to be one of the government’s highest foreign policy priorities. In the Prime Minister’s own words (during his 2019 visit to Vietnam), Australia wants a region of “sovereign, interdependent states, resistant to coercion but open to cooperation on the basis of shared interests”.

Similarly, Foreign Minister Payne’s speech on the Indo-Pacific in March drew heavily on White Paper concepts and language.

While the Indo-Pacific strategy remains front and centre in Australian foreign policy, the period since the White Paper has seen significant new policy muscle added to it.

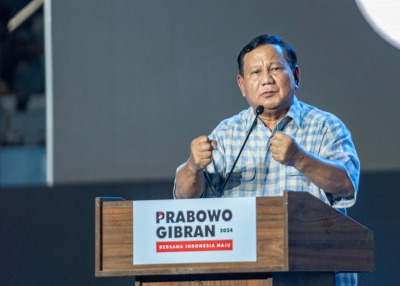

The Pacific “step up” has more firepower. The Turnbull and Morrison governments sharpened their focus on Australia’s major Asian partners, especially Japan, India, Vietnam, Indonesia, Singapore and the Republic of Korea, and ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations). The recent Australia-India virtual summit, with its long list of outcomes and agreements, is illustrative of these efforts.

Australia’s aid program has been substantially re-geared to respond to the public health and economic effects of the pandemic – with a strong Indo-Pacific focus – through new “partnerships for recovery.” Helping regional countries access COVID-19 vaccines is a priority.

The Morrison government wants like-minded countries in the region to work more closely together. The pandemic has provided new opportunities for this cooperation, including through a “seven country” Indo-Pacific coordination mechanism, in which Australia works with India, Japan, New Zealand, the Republic of Korea, the United States and Vietnam.

Australia has worked to keep the U.S. Alliance strongly geared towards the Indo-Pacific. And the recent 2020 Defence Strategic Update decisively shifted the focus of planning to Australia’s “immediate region”. Capability upgrades will (in time) boost the Australian Defence Force’s lethality and ability to deter regional adversaries.

The past three years have been least kind to the White Paper’s framework for bilateral relationship with China, with its emphasis on maintaining “positive and active” engagement while hedging against risk.

More than anything, this model has collapsed under the weight of Beijing’s own conduct. Policies to protect Australia’s sovereignty and security and assert its values – whether on cyber security, foreign interference, human rights or an inquiry into the origins of the pandemic — have sparked a wave of retaliation from China, freezing the political relationship and threatening Australian exports.

Meanwhile, U.S.-China competition has become sharply more confrontational and politicised. The Morrison Government has a genuine dilemma here. Australia wants the United States to compete with China and to push back against bad behaviour, but the government also sees risks to Australian national interests in being caught up in the increasingly hostile and ideological framing of the US-China contest.

The prime minister and the foreign minister have been clear in recent weeks that while U.S.-Australian interests are strongly aligned, they are not identical. In other words, Australia won’t always follow the U.S. policy lead.

Where to now?

Australia is gingerly navigating its way through a smashed-up COVID-19 world: a world in which disease, death and a shattered world economy are overlaid on any number of global trends that on their own would pose a challenge for Australian foreign policy.

Australia retains great national strengths. But in 2020, we also start from a weaker position than we did in 2017 — a damaged economy, high unemployment, much higher debt, closed borders and an imperative to focus domestically. Many of our neighbours are in a worse position. Many, understandably, are more concerned about economic recovery than longer-term challenges like balancing China’s power in the Indo-Pacific.

Such is the rate of change over the past three years that there is an argument now for a formal review and update of the 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper. A hard-pressed government and bureaucracy could no doubt do without the added headache. In any event, such an exercise would need to wait for the dust to settle on the November US Presidential election.

These are serious considerations. But, three years on, there is enough new policy to draw together and enough unanswered questions to make the hard work worth the effort.

An update to the White Paper, like the Defence Strategic Update, or perhaps through a ministerial statement to Parliament, could unify the strands of evolving policy. It could flesh out the Morrison Government’s narrative of resilience and self-reliance.

There are some more difficult issues to explore. A balanced but clear-eyed appraisal of the challenges of dealing with a more ideological and nationalist China, for example, might help drive greater national consensus on the future terms of the bilateral relationship.

More limited and tense ties are here to stay for the foreseeable future as Australia responds to Chinese actions that clash with our interests and values. There will be more occasions where an economic price may need to be paid to protect Australia’s security and independence of decision-making.

Equally, an update to the White Paper could recognise that for the foreseeable future China will remain our largest export market, and that this too is an important national interest, not a liability.

The government could reinforce its recent messaging that while Australia’s interests are often aligned with the United States on China, they are not identical.

With a bit of luck, even in such straightened economic times, a White Paper update might address the growing imbalance between the diplomatic and military arms of our Indo-Pacific Strategy. It could provide a platform for further lifting our work rate in Asia, especially in Southeast Asia.

An update might tease out how the stronger emphasis on values in Australian foreign policy should apply not just to China but to close and important partners elsewhere in the region with poor human rights records. And it could frame an agenda for a new U.S. administration, whether Trump 2.0 or Joe Biden.

The re-gearing of the development assistance program to meet urgent COVID-19 needs is welcome. But, despite the immensity of the COVID crisis in our neighbourhood, not one new dollar was added to the overall aid budget. Surely this is inadequate for the task of investing in the region’s economic recovery – a pre-eminent Australian national interest if ever there was one.

If a permanent re-basing of Australia’s development assistance program can’t be contemplated, then even a generous one-off boost for COVID relief in Asia would show the region Australia is there for it at a time of need.

The Australian Council for International Development, for example, has advocated for a four-year $2 billion COVID aid package, something akin to John Howard’s $1 billion response to the great 2004 Boxing Day tsunami that struck Indonesia and other Indian Ocean nations.

Meanwhile, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade continues to shrink under immense budget pressures. Boosting Australia’s hard power in our current geo-strategic circumstances makes sense. Short-changing diplomacy does not.

Australia will also need to think harder about the United States and its place in the world, regardless of the outcome of the Presidential election.

If President Trump is re-elected, Australia faces the unpalatable prospect of having to hedge more against its Alliance partner. The relationship is and will remain essential. But even a greater degree of independence within the Alliance won’t be sufficient to meet the challenge of a re-elected Trump Administration.

The few guard rails and electoral constraints that exist on the populism and narrow nationalism of America First will be knocked aside. The differences in our respective national outlooks on rules-based order, on the Trump Administration’s propensity to abandon multilateral commitments without an effective plan B, on trade, and even on China, despite sharing many US concerns, will be accentuated.

Caught between an aggressive and punitive China and a less predictable America, Australia’s challenge will be to protect its sovereignty without foreign policy becoming so rigid that it closes down the nation’s options.

We are likely to say “no” to the United States more often. Our direct relations with major Asian partners like India, Japan, the ROK, Indonesia and the rest of Southeast Asia will become even more important ballast. We may want to work more closely with partners in Europe who share a similar commitment to a free trade and, with all its imperfections and frustrations, a rules-based component to global order.

On paper, a Biden Administration would ease some of these points of tension between U.S. and Australian national interests. But Australia would be pushed hard for more ambition on emissions reductions. And Biden’s campaign reflects America’s mood, embracing industrial policy and supporting free trade only cautiously.

Australia won’t want a stronger emphasis on values to constrain US engagement with partners like Vietnam and Thailand, or even India. And while some lowering of the temperature of US-China relations will be welcomed, policy makers in Canberra also won’t want US pushback against China to become negotiating coin on other issues, even important ones like climate change.

There is, of course, much more to be said and done. Foreign policy throws up more questions than answers in such a volatile and unpredictable environment.

But an update to the White Paper need not pretend to be the final word, nor even a new beginning. Rather, done well, it would build on what has come before and in doing so strengthen the foundations of Australia’s security and prosperity.

Richard Maude is Executive Director of Policy at Asia Society Australia and a Senior Fellow of the Asia Society Policy Institute. He is a former senior public servant who led the whole-of-government 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper taskforce.

An edited version of this essay first appeared in the Australian Financial Review on 10 September 2020.

Asia Society Australia acknowledges the support of the Victorian Government.