Interview: Creating 'Wenji: Eighteen Songs of a Nomad Flute'

Interview with Bun-Ching Lam and Rinde Eckert

Wenji: Eighteen Songs of a Nomad Flute is a contemporary opera based on the true story of poet and musician Cai Wenji. The opera tells the story of a scholar's daughter who becomes a prize of war and is torn between two worlds during the Han Dynasty. The piece is composed by Bun-Ching Lam, written by Xu Ying, and directed by Rinde Eckert. The opera is co-produced by the Hong Kong Arts Festival.

Bun-Ching Lam is a versatile composer whose wide catalogue of works have been praised as "hauntingly attractive" by The San Francisco Chronicle. Born in the Portuguese colony of Macao, Bun-Ching Lam first studied piano at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, and later received a Ph.D. in Music Composition from the University of California at San Diego. Defying cultural boundaries, her work stretches both Chinese and Western musical idioms to create a highly personal and compelling musical voice.

Rinde Eckert is a writer, composer, singer, actor, and director whose music, music theater, and dance theater pieces have been performed throughout the United States and abroad. Called "a jack of all stage arts" by The New York Times, he has collaborated with composer Paul Dresher, with whom he has written, performed or directed 10 pieces of theater or dance since 1980. Rinde Eckert has also worked extensively with the Margaret Jenkins Dance Co., first as a writer performer, and later as a composer.

Asia Society spoke with the composer and director during rehearsals in the Asia Society New York auditorium.

What is it about the Wenji story that attracted you?

Bun-Ching Lam: First of all, Wenji is a poet and musician. The story is very well known in China as are musical interpretations of the story. Also the whole situation of her being a woman and being kidnapped during a war seemed to relate to the contemporary world in which we live. Women still have no choices. They are commodities, and whenever there is a war they are [moved around]. The interracial marriage is also very interesting in Wenji. All of these issues come together in this story.

Do you see Wenji’s search for home as a universal theme?

Bun-Ching Lam: Absolutely. It is especially important if you are a self-imposed exile such as myself.

Rinde Eckert: Even though I am a native-born American, I have had great difficulty identifying my culture. I don’t identify with the bourgeois aesthetics of America. I tried to take refuge in European culture by studying classical music, but that didn’t feel at all like home either. I finally relegated myself to the fact that I was a nomad. The way that I approach this project is from the standpoint of a nomad who shares many of the characteristics of the nomadic bretheren in the story, which are a certain degree of pragmatism, and a kind of poetic spirit as well. Poetry tends to be a more nomadic form than the novel. In the nomadic community you have only the stuff you can carry with you, so you don’t write vast tomes, you write epigrams and poems. The relationship to nature is different. When you have that nomadic spirit you start looking at these larger connections rather than discrete cultural connections. In many ways what is expressed here in Wenji is that for the nomads, race is not really that much of an issue. Diversity is a matter of form, at least as expressed in this opera. I’m sure that’s not true in normal life. I’ve tended to generalize my own situation as nomadic and I have had to establish my own cultural norms a very idiosyncratic artistic perspective in my own work, which completely resonates with Wenji.

How do both the set and the music reflect this nomadic culture?

Rinde Eckert: In the way that we’ve approached this, we’ve tried to use several of these as touchstones. The idea of the Silk Road was important, as there was a Silk Road exhibit at the Asia Society and the set is made largely of silk cloth. That has another advantage in that all of the elements are transportable. There’s no sense that anything is hidden. We’ve tried to expose everything on stage to reflect nomadic culture. Everybody sees what you have. It’s not under lock and key. You have to be able to pack it up and take it out again.

We’ve reflected that in the way that we approach Wenji. It’s a very sparse world, almost like a pavilion. The whole stage is like a huge tent. I’ve also tried to allude to certain elements, like the scholarship of Wenji. There’s this moment in the beginning when the first time we see Wenji, she’s a scholar delivering a lecture. We focus on the scroll, and she’s finishing her lecture on that scroll, which also has the great advantage of telling us the story of Wenji before we see it. We set it firmly in a modern context in a very simple way, and then we tear down the wall between the modern world and the ancient story. There’s a sense that we’re dividing the world into a modern, sophisticated culture, and into antiquated culture, but the two are separated by this illusory film and once we tear down this film we see that the concerns of the past are also the concerns of the present. The distance between the two worlds is illusory. Even though this scroll that we see in the beginning is of the past, it’s entirely relevant and any notion to the contrary is illusory.

We’ve also divided the world into West and East to a degree. There are all sorts of divisions. We’ve created a cloth division between the orchestra and the stage, so the space itself appears to be divided. There’s also the difference in race between Ethan Herschenfeld, our king of the nomads, and Li Xiuying, our Wenji. East and west is intrinsic to this interpretation.

Does the music reflect that difference between East and West?

Bun-Ching Lam: There’s a subtle difference in musical style. The music shifts to a more “Western” style as the opera progresses. At first Wenji sings in Chinese most of the time, but in the end she sings more in English.

Rinde Eckert: The instrumentation is quite eclectic. We have English horns and cello as well as a whole battery of Chinese percussion instruments. In the sonic world, it draws on [both Chinese and Western traditions].

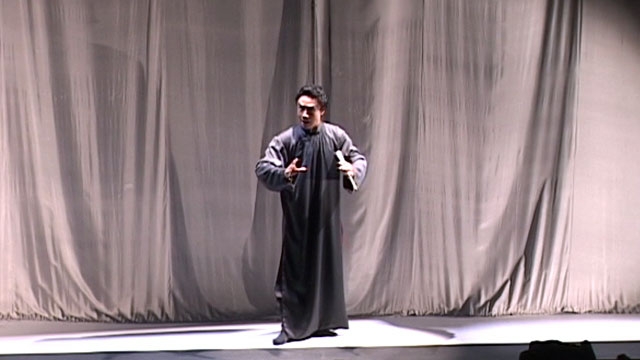

Bun-Ching Lam: Particularly with Zhou Long, who is a Beijing opera performer, the way he sings is with a totally different vocabulary than a Western performer. Wenji sings in-between [East and West], she switches styles and languages.

Wenji is a bilingual project, bilingual in the sense that the creative team is bilingual, but also in the sense that the music is bilingual and Wenji herself is a bilingual, bicultural figure. What dimensions does working in two languages add to the performance?

Bun-Ching Lam: I insisted on a balance. I insisted on having Rinde as a director instead of a Chinese director. I wanted that Western perspective and to see what he could bring from the other side.

How do you go about contextualizing the story of Wenji, placing it in a certain time period and also making it universal and contemporary? Do you have to balance those two things?

Rinde Eckert: Yes, you do have to balance. It’s reflected in the costuming, it’s reflected in the types of movement on stage. Zhou Long himself represents a type of anomaly because the movement is a classic Chinese form that goes back a long way. He represents this tradition, but he’s in the most modern dress on stage. In every element we have expressed these dichotomies. The old and new are available in everything on stage. Yet it should not have a sense of a kind of eclectic pastiche, but of a real aesthetic, which it does. I think we’re actually coming closer and closer to what Xu Ying has written down in the script. I started with notions that were farther removed from the script, but as I’ve been directing, I’ve come back to the script. Stage directions that I had ignored before I am returning to…. I think Xu Ying has anticipated that quite well. We have been moving in each other’s directions and as a result we’re coming to something with a great deal of artistic integrity. It doesn’t feel like we’ve just stuck a couple of things together.

Rinde Eckert: One thing Xu Ying and I share is a sense of theatrical integrity and I think ultimately I’ve discovered that we often both agree that this is really good despite our differences. I feel like we see the same thing. We both see theatrical integrity, me from my western perspective, Xu Ying from his Chinese perspective and in the same way we both find it touching or illuminating or amusing, or whatever it is. Every moment in this piece I can look at Bun-Ching and Xu Ying and ask, “are we all seeing what I’m seeing?” and if everyone is seeing the same thing, I feel like we’re really getting to something.

Do you think audience reaction will be different in New York and Hong Kong?

Rinde Eckert: Undoubtedly the reaction will be different. It will be a lot more exotic to the New York audience, although it will be a little bit exotic for the Hong Kong audience as well because it’s a different approach. People in Hong Kong will see it as a very modern piece, while people here will see it as an ancient story telling. So they’ll be seeing it from different points of view — in Hong Kong as a radical departure and in New York as connecting with a tradition. Curiously, those people who come at it from the opera world will share more affinity with the Hong Kong audience than with other New Yorkers. They’ll just see it as an operatic tradition.

Bun-Ching Lam: Hopefully the two traditions will work together instead of opposing each other. In music you shouldn’t really hear two different traditions, you shouldn’t feel oh, that’s Western music or oh, that’s Eastern music. You shouldn’t be surprised when all of a sudden someone is speaking English and then they’re speaking Chinese because it’s normal [to be bilingual].

One instrument in particular, the qin, is an important symbol in this piece. Why?

Bun-Ching Lam: Qin is a scholar’s instrument and it really represents Chinese Confucian culture. Confucians used to play qin and compose for it. It’s really the most esteemed instrument and more a symbol than an instrument. Wenji’s father was a wonderful scholar and had written books about the qin and played the qin. There were stories that Wenji was very talented on the qin. One story is that her father was playing qin in the next room and Wenji could tell when a string broke [on the qin] and which string it was. The qin symbolically stands for China, and for Chinese culture.

Bun-Ching, you’re trained in Western classical music, but you have composed pieces using Chinese instruments like the pipa before. How is Wenji different from your other works?

Bun-Ching Lam: This is a continuation of my previous work. This is certainly the largest scale I've ever worked on.

Well, we look forward to seeing the finished piece.

Interview conducted by Michelle Caswell, Asia Society